Born in Batala in the Punjab in 1946, Deepak Nayyar studied at St. Stephen’s College, University of Delhi before going to Oxford to read for a BPhil in economics. He worked for a period in the Indian Administrative Service and took his DPhil in economics at Oxford before a period of university teaching in England. Returning to India in 1980, Nayyar taught at the Indian Institute of Management, Calcutta and was then appointed professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. From 2000 to 2005, he was Vice-Chancellor of the University of Delhi. From 2008 to 2012, he was Distinguished University Professor of Economics at the New School for Social Research, New York. During 2022-23, he was invited to the Kluge Chair in Countries and Cultures of the South at the United States Library of Congress, Washington DC. Nayyar’s academic career has been interspersed with periods working for the Government of India, as Economic Adviser in the Ministry of Commerce, Chief Economic Adviser to the Government of India and Secretary in the Ministry of Finance. He served as the Chairman of the Board of Governors of the World Institute for Development Economics Research, Helsinki and has held a number of key roles leading and supporting academic and research institutions. Nayyar is an Honorary Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford. He is currently Chair of the Board of the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex, and Chairman of the Sameeksha Trust, which publishes Economic and Political Weekly. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 11 October 2024.

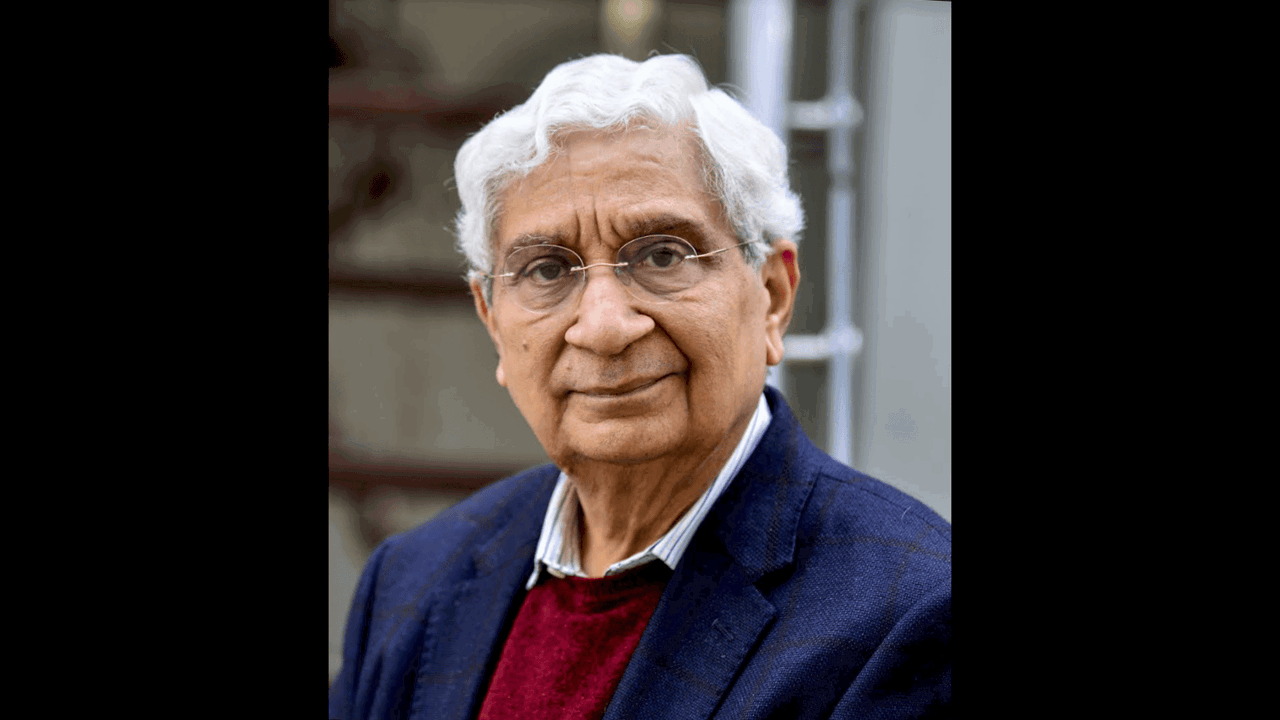

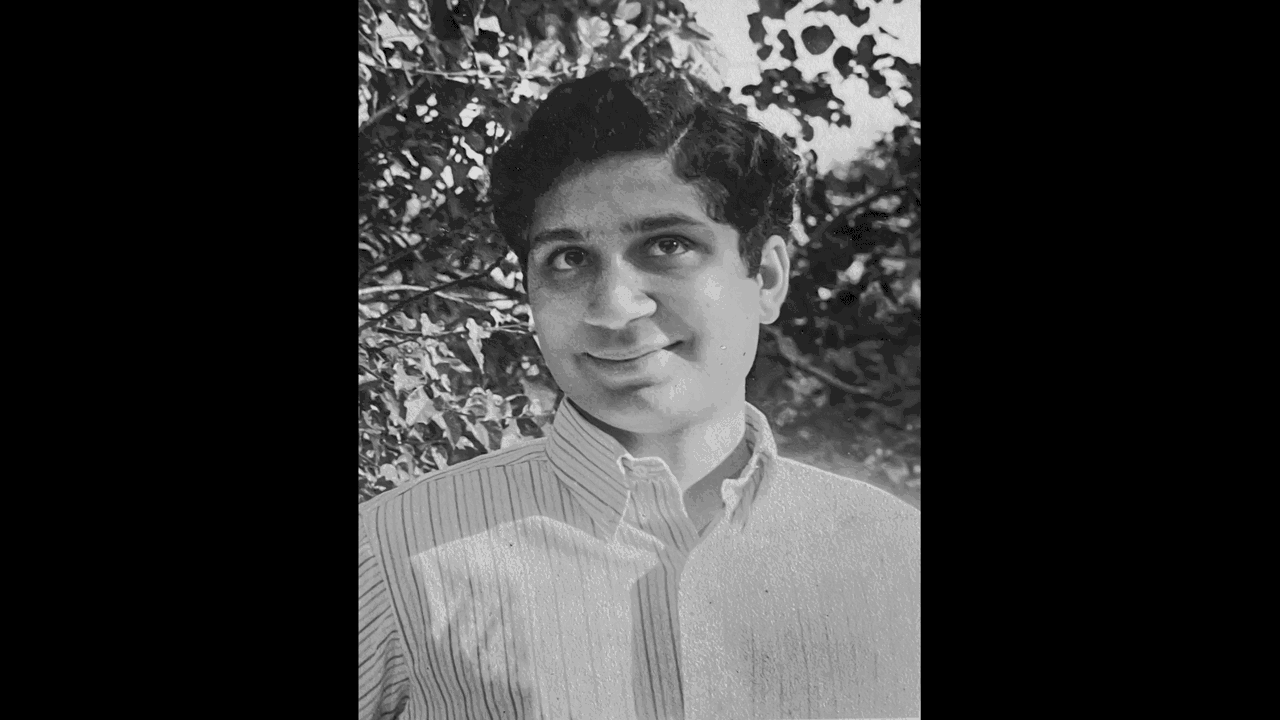

Deepak Nayyar

India & Balliol 1967

'You could describe me as one of ‘Midnight’s Children’

My lifetime coincides almost exactly with that of independent India. You could describe me – in the words of Salman Rushdie – as one of ‘Midnight’s Children.’ My father was a civil engineer who worked for the government of Punjab and we moved often, whenever he was transferred. Over eleven years, I went to five different schools. I grew up in small-town India where poverty was widespread. I often sat on the floor in school and we would write on slates. An occasional visit to the cinema, usually once a year, was about our only entertainment.

I went to Hindi-medium schools for most of my childhood, which had an enormous influence on my evolution as a person. The first English-medium school I went to was St. Xavier’s, a Jesuit school in Jaipur. I remember with great affection Father Extross, who said to me one day, in despair, ‘Son, you are incredibly bright, but you will never learn to speak or write English.’ He was right in the short term, although he turned out to be wrong in the long term!

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

To my surprise, I made it to St. Stephen’s College at the University of Delhi. When I got there, I felt like Alice in Wonderland. Most students came from elite English-medium schools, and the first year was incredibly tough. But if you’re thrown in at the deep end, you learn to swim, somehow. St. Stephen’s provided me not only real educational opportunities but also equal opportunities, with students and teachers who were conducive, supportive and encouraging. It took me some time to break the ceiling when it came to English as a language, but I did. This led me to engage in debating and writing. I also developed my love of photography.

I stayed at St. Stephen’s to do an MA in economics, and that was when I applied for the Rhodes Scholarship. In retrospect, I think it must have been an adventurism bordering on bravado that made me do it. I could never have afforded to go to Oxford on my own, and I wanted to study there, so the Scholarship provided a means of doing so. I was most pleasantly surprised when I was shortlisted, but I do remember that for the dinner and the interview, it was mandatory to wear a suit, and I did not own one. All my friends rushed around, about six suits were produced, and I wore one which was still a loose fit. I remember one gentle soul in the selection committee said, ‘Young man, I think the suit is not your own,’ and I said, ‘That is absolutely correct.’

‘A fascinating experience’

I travelled from Delhi to London by plane, and it was the first time I had been on an aircraft. At Paddington, I had a wait to catch the train to Oxford, so I got a cup of tea and a biscuit, and I remember the lady who served me said, ‘Three and tuppence ha’penny, love,’ and I simply didn’t understand that she meant three shillings, two pence and half a penny. It was a different culture and a different world.

Oxford was a fascinating experience for someone like me. Quite apart from learning about a new country, the coexistence of college life with university life was unique. Living at Balliol, I was able to interact with students across so many different subjects. Economics was part of the social sciences group and there were intellectual synergies between different subjects. I remember a conversation with John Hicks, who was a legend in economics by then, and he asked why I had come to Oxford, given that I had already been taught by real stars like Amartya Sen at the Delhi School of Economics. I said, ‘I have come to Oxford to learn to resist the authority of the spoken word from teachers and the printed word of books or journals. We have a good system of education in India, but we are never allowed to question.’

It was a turbulent time in Oxford and in universities across Europe, with students protesting against authoritarian rule by establishments: against the US war in Vietnam, the USSR invasion of Czechoslovakia, and apartheid in South Africa. It reinforced my thinking about the importance of freedom, fearlessness, democracy and peace. One other thing that was very important to me was the opportunity of meeting and talking to Christopher Hill, who was then Master of Balliol, about his approach to and understanding of history. Our conversations over two years really stimulated my interest in history. Later, in my professional life, I have done a lot of work at the intersection of economics and history.

‘Individuals can make a difference to institutions’

I always wanted to be an academic, but while I was at Oxford, I did the civil services examination for India. To be honest, I did in solidarity with my fiancée Rohini. We had met as students and were married in 1969, and she wanted to be in the Indian Administrative Service to pursue her passion for working on rural development. Both of us were selected and served in the Uttar Pradesh cadre of the IAS. It was something completely different for me, a grassroots experience that helped me understand the nature of our polity and society and the problems confronting ordinary people in their daily lives. It was my first exposure to poverty and inequality, deprivation and exclusion, corruption and injustice, caste and discrimination, or power and politics. This grassroots experience led me to abandon the esoteric world of economic theory to work at the intersections of theory and policy, in macroeconomics, international economics, and development economics.

I went back to Oxford to write my DPhil thesis, and then to India. By that time, both Rohini and I together had decided we no longer wanted to continue working in the IAS. We returned to England, where I did university teaching in Oxford and in Sussex, until 1980, and then we went back to India again. I taught at the Indian Institute of Management in Calcutta, and then worked as Economic Adviser in the Ministry of Commerce in New Delhi. From there, I moved to a Chair the department of economics at JNU when I was appointed professor there. I returned to government a third time in late 1989, as Chief Economic Adviser to the Government of India, in a period of great political turbulence in the midst of the deepest macroeconomic crisis in independent India. I have worked on macroeconomics for a lifetime, but this was an experience of at least two lifetimes in the macroeconomics of development. It was about managing an acute macroeconomic crisis and averting a default on our external debt obligations, with three successive governments. I negotiated with the IMF to secure support for India. It was a difficult period, but also one of enormous learning. More importantly, we managed to overcome the crisis and stabilize the economy.

‘I have lived in different worlds’

In spite of my three tenures in government, engaged with public policy, I am an academic at heart and the classroom has been my natural home. Most of my friends in academia never understood why I left the engaging world of the classroom, ideas and creativity for the hurly-burly of the public domain. Most of my friends in government never understood why I left the real world of power, influence, and excitement in the public domain for the ivory tower of academia. The fact is that I enjoyed both these worlds and never thought of them as an either-or choice. In fact, I am convinced that I left both richer for the experience, which enabled me to contribute more to the other world when I returned to it.

I have always enjoyed teaching, particularly small group teaching, and I have always taught my students the orthodox, the heterodox and the unorthodox. Alongside teaching, my research and publications have spanned a very wide range of areas, which is unusual in the narrowly specialised world of economics. I learnt my economics in teaching, research and policy practice, and I think it is that interaction which makes my interests so diverse. During my professional life, I have also led and nurtured a large number of academic and research institutions, because, while institutions are always much larger than individuals, I do believe that individuals can make a difference to institutions.

What motivates me now is the same as what has motivated me throughout my life: a desire for an Indian democracy that truly transforms us from being subjects into becoming citizens, and a wish to eradicate poverty and discrimination in our economy and society. For India, that is an unfinished journey in all respects.

If I were to live my life again, I would be happy to do exactly the same. I have spent time in different worlds and lived a more unusual life than most, and I have enjoyed it so much. To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say what I have always said to my students. First, you have just one life to live. Do what gives you satisfaction and joy. Second, remember your obligations to society. And third, there is more to life than the world of work!