Born in Toledo, Ohio in 1952, David Johnson studied at Harvard and then went on to Oxford to read for a second BA in modern history. After returning to the US and qualifying as a lawyer, he worked on Capitol Hill before moving back to his childhood home of Indianapolis. A longtime business leader and regional economic development strategist, Johnson led the effort to raise Indiana’s first institutional life sciences venture capital fund, initially as a community volunteer. He went on to become one of the founders and, for 20 years, the leader of BioCrossroads which provides a supportive ecosystem for Indiana’s life sciences industry sector and entrepreneurial community. He has also served as the CEO of the Central Indiana Corporate Partnership, a regional collaboration of executive leaders drawn from industry, academia and philanthropy. Johnson is a strong supporter of the Rhodes Trust and has served over many years on selection committees for the Rhodes Scholarship. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 5 December 2024.

David Johnson

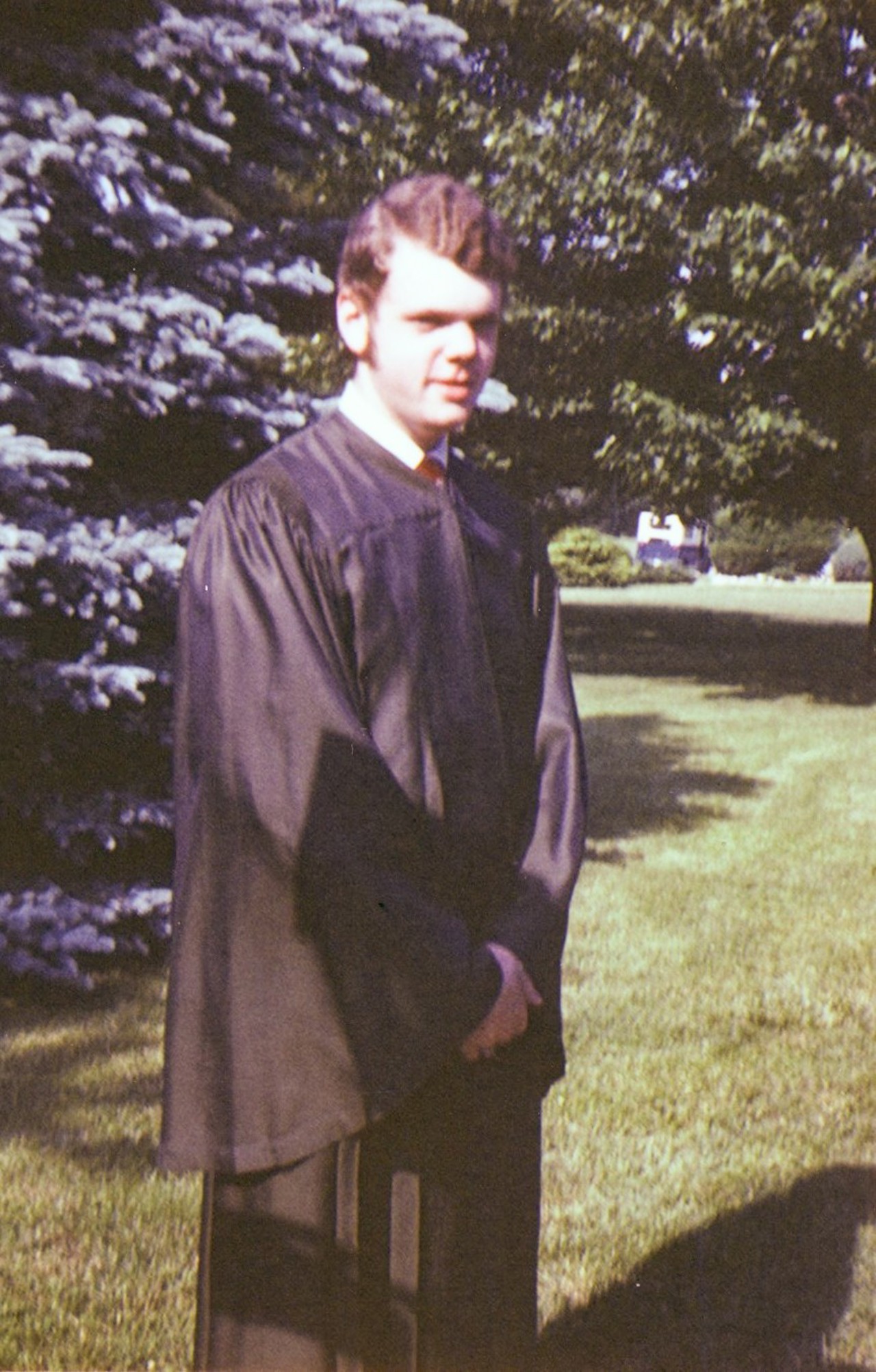

Indiana & New College 1974

‘My high school education really taught me how to be a citizen’

I was born in Ohio but most of my childhood was spent in Indiana, where my father, a Presbyterian pastor, had been called to serve a church in Indianapolis. My mother’s family had been Presbyterian too, and both her father and grandfather were Presbyterian clergymen. Not surprisingly, she determined from an early age that she would never marry a Presbyterian pastor. She met my father when they were both in college, before he had decided to go to seminary. Thankfully, when he made his decision to go, she stuck with him.

As a kid, I was shy and introverted, all the more so because I was also a very bad asthmatic. No one was mean to me about it, but it meant I always felt excluded from sports and activities involving other kids in my neighbourhood. Under intensive treatment, my asthma got better as I got older, but my parents had some anxious times until then. They were wonderful people, always grateful to the world for the opportunities they had and never resentful that they didn’t have more. And they encouraged my own growth, education and curiosity in so many helpful and loving ways.

I did well academically, and my high school education really taught me how to be a citizen. I was at high school during desegregation and bussing, and ended up leading a forum to bring black and white students together to discuss racial incidents and help diffuse tensions in the school at that challenging time. I was also editor of the school newspaper. I was fortunate to win a summer high school journalism internship at Northwestern. Every kid there was planning to leave home and go to college. It made me see that there were options I’d never thought about before.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I ended up going to Harvard, in the early 1970s’ era of student strikes, which were intriguing in some ways, but unsettling and disruptive in so many others. Academically, I was interested in political philosophy and history. I ended up doing a major called social studies, which gave access to top-flight professors in different areas. I also got drawn into student government, where we were pushing for was both the admission of greater numbers of women to Harvard and, once they were there, a better and more truly shared educational experience for everyone.

I’d never heard of the Rhodes Scholarship before but at Harvard, the idea was in the water. I didn’t want to be one of those people who went on to law school or a Wall Street firm straight after college, so the Scholarship was very appealing in that way. Unlike the selection committees I’ve sat on, the interviews then were very much designed to rattle you. They just pummelled you with questions. One interviewer kept asking about my involvement in gender equity issues in student politics and, given that, how I could be applying for a men-only scholarship? I said I thought the only way change would happen was if people inside the programme were actively pushing for it, and that this was precisely the approach that my women counterparts in our student government were urging all of us guys to pursue. After that, he had nothing more to say.

‘It was amazing to me how different England was from the US’

I still remember arriving at New College with my suitcase, and the gatehouse door opening to these beautiful eighteenth-century buildings and gorgeous gardens. I lived in college my first year, and with such an interesting group of people. I would not say that academics were my first priority at Oxford, though they were important, and very rigorous. I was reading modern history, and in Oxford that meant everything after the fall of the Roman Empire.

My first priority was to be sure I made good use of the gift of time the Scholarship brings. It was amazing to me how different England was from the US, how different the economy was and how intense the class system was too. I ended up playing guitar and singing in a bar in one of the rough parts of the city, where you weren’t allowed to stop singing, because without background music, people were likely to get into a fight. Other than the cold, the only thing that was really bad about Oxford was the terrible English food. So, a group of us learned to cook, and from that, I learned the joy of cooking. My wife would tell you that I didn’t learn nearly enough!

‘It’s been a very gratifying set of opportunities’

At law school, when friends of mine were busy trying to figure out what firm they wanted to apply to, I was getting more and more interested in the independence movements that were going on in sub-Saharan African countries at that time. That was in large part because at Oxford, I’d made some very close friends who were from what is now Zimbabwe, and from South Africa. Through perseverance and considerable luck, I landed a junior position on the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee. I ended up staffing the African Affairs subcommittee while also serving as the caucus lawyer for the Committee’s Democratic members. It was a ridiculous amount of responsibility for someone in their 20s.

That was a hard job to leave, but by then, I had met my wife, who was still a law student. Especially at that time, when people changed jobs and moved between cities far less often, we knew the only way a two-career couple could both find satisfactory jobs was to try to make one big move together that might work over the long term. One of my mentors at the time, an experienced lawyer and Rhodes Scholar himself, advised that if I wanted to be a lawyer with some connectivity to my community, I should head back to Indianapolis. As it happened, my wife already had an attractive offer from a law firm there, and so that’s what we did.

I built up a law practice in public finance while also getting involved in the campaign of a family friend who was running for governor. I grew more and more interested in doing something like that myself. With considerable help and support from family and friends, I ended up launching a spectacularly unsuccessful campaign for the U.S. Senate. Running that race taught me a lot, not least that I didn’t actually have the “fire” to be successful in elective politics, but also that I didn’t have the ambition to continue any longer as a practicing lawyer.

As a volunteer, I had always been drawn to community and economic growth opportunities, and so I started to focus increasing amounts of energy there. I ended up putting together a venture capital fund that could provide local capital for biotech startups that were just starting to come out of the region’s research universities. From there, we formed a life sciences sector development organisation, BioCrossroads, which I was asked to run, and that’s what I did for the next 20 years or so. Understanding how money is raised and how philanthropy and corporate investment and the public sector come together are all things that you truly learn only by doing. I’ve retired now, but I’m still involved in projects to pull those strands together. It’s all good work—and it’s impossible to fully leave it!

‘When you’re given an opportunity, you owe’

The Rhodes Scholarship had a profound impact on my life. Without the Rhodes Scholarship, I would never have had the confidence to say, let alone believe, ‘I’m going to make this happen’ at various points in my career.

I’ve had a very privileged life, fully shared with my wife, Anne, and our extraordinary daughter, Catherine. I have wonderful friends and I’ve been able to do essentially what I always thought that I wanted and needed to do. I don’t have any illusions that this kind of joy is anything I’ve earned. When you’re given an opportunity, you owe, and you keep working with it. Life is just more fun if you’re open to new challenges and don’t ever assume you have—or you ever could--figure everything out.