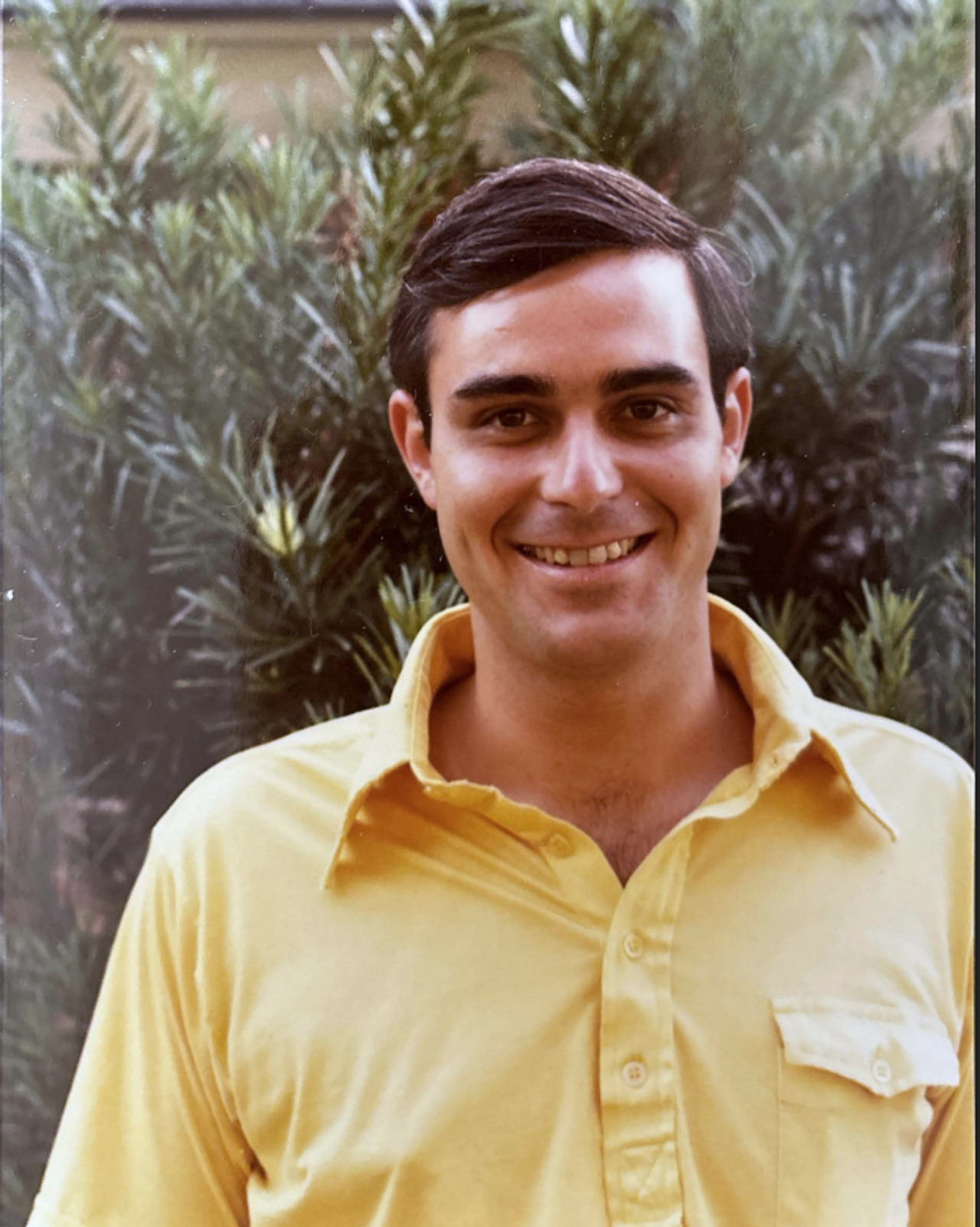

Born in Shields, Illinois in 1961, David Frederick studied at the University of Pittsburgh before going to Oxford to take his DPhil in comparative politics. Returning to the US, he earned his JD at the University of Texas Law School and then began practising as a lawyer. After a period clerking, Frederick worked as an assistant to the Solicitor General. He has argued more than 60 cases in the US Supreme Court. Now a partner at Kellogg, Hansen, Todd, Figel & Frederick, he continues to work on landmark cases that champion consumer interests, pharmaceutical safety and environmental protection. He is also the author of Supreme Court and Appellate Advocacy, now in its fourth edition. Frederick is a generous and longstanding supporter of the Rhodes Trust and of other educational institutions. He and his wife, Sophia Lynn, have made a philanthropic gift that resulted in the naming of the Honors College at the University of Pittsburgh as the David C. Frederick Honors College. The couple have also gifted and spearheaded an innovative philanthropy project linking the Honors College with University College, Oxford, where Frederick is a Foundation Fellow. This narrative is excerpted and edited from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 11 December 2024.

David Frederick

Texas & University 1983

‘It planted a seed’

I was born at Great Lakes Naval Station, because my father had been drafted into the military out of a medical residency. When he completed his service, he and my mom moved back to San Antonio where we settled. I have an older brother and a younger sister. We attended public schools in San Antonio, which was the third largest city in Texas at the time and had a very international feel to it.

My parents instilled in me a love of music – they had actually met when they were singing together – and I also enjoyed sports. I was very active in the speech and debate team, and that really came to dominate my time. I won second in the nation in original oratory and second in extemporaneous speaking (in different years). A judge in one of my competitions at a local oratory contest was a lawyer. He pulled me aside and said, ‘You should really look hard at becoming a lawyer.’ I didn’t know anything about the legal profession, but it planted a seed that later germinated.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I had zero college counselling as a high school student, and my applications were pretty aimless. But I had gone to a summer debate institute at the University of Pittsburgh and when Pitt offered me a scholarship, I took it up. The honours programme there had just launched when I arrived, and I joined it and took a course on ‘Ideas in America.’ I came away challenged and energised, and that became a launching pad for me. Alec Stewart, who was running the programme, suggested I apply for a Truman Scholarship, which I won, and then he said, ‘You might want to think about other scholarships, like the Rhodes.’

I was the first Rhodes Scholar from the University of Pittsburgh, and I have always felt a special responsibility for that. It was an extraordinary opportunity for me, absolutely life changing. I have felt very proud to help other students from Pitt and be as good a role model as I can, giving back to my universities and to the Rhodes community. Winning a Rhodes Scholarship really is a moment when lightning strikes.

‘The really meaningful thing for me was the friends I made’

At Pitt, I had written a political science thesis that looked at why dictatorships in Iran and Nicaragua had failed. The focus was on how power is amassed and ultimately lost. I decided to expand that idea and it became the inspiration for my Oxford DPhil. I had actually planned to do an MPhil in international relations at Oxford, but when I outlined my thesis idea, the advisor said, ‘That sounds really interesting, but it’s not an international relations thesis.’ So, I was still trying to find my way around Oxford when I also found myself changing courses and moving to the politics sub-faculty. Because of my specialty, and because of professors going on leave and so forth, I ended up having five different supervisors across the course of my nine terms reading for the DPhil. I even had some sessions with a wonderful tutor at Warwick University. I had to be very disciplined to get the work done in the time that I had.

The really meaningful thing for me was the friends I made in Oxford, and especially at Univ, which was a particularly hospitable place and very friendly to foreign students. My first day in Oxford, a few of us were looking around and we saw this guy come out of a pub and start cursing up a storm because he’d been blocked in by a Mini Cooper. He was threatening to bash the car up just because it was in the way. So, three of us just picked up the Mini Cooper and moved it about a foot, the guy drove away, and then we moved it back. Well, the guys that moved that car with me are still my good friends, and we still laugh about that story.

The Rhodes Trust stipend gave me the chance to travel while I was at Oxford, both for my academic work and just to explore. In my first year, I travelled to the Soviet Union, Paris, and Spain, which were eye-opening in their differences. The then-Warden of Rhodes House, Robin Fletcher, arranged a very generous bursary so that I could travel to Cuba and Nicaragua to do research for my DPhil. I was an avid concert and theatre-goer too, so I would travel down to London frequently. And when I wasn’t doing that or writing my thesis, I was rowing. It wasn’t something I’d done before, but I became really passionate about it.

‘One good result begets more cases’

I’m pretty convinced that being a Rhodes Scholar mattered as a credential when I applied for a Supreme Court clerkship. Being hired for that role to work with Byron White (Colorado & Hertford 1938) was completely transformative for me in the profession of law. When I was at the Supreme Court, I started to see oral arguments by lawyers and I hearkened back to my time as a high school and college debater and thought, ‘I think I could do that.’ When I went on to work in the Solicitor General’s office, I had the chance to be one of the counsel who argued the appeal of the government’s case against Microsoft for its operating system monopoly. It was the most important antitrust case of that period, but I don’t think I realised it would be a landmark decision we would still be reading 24 years later as the seminal technology anti-trust case.

When I told friends about the work I had been doing preparing for oral argument in the Supreme Court and Court of Appeals, several of them said, ‘You should write a book about that.’ I did, and writing it brought together the oral advocacy skills I had learned as a student with the discipline of sitting by myself in Oxford, writing a 100,000-word thesis. Once I’d written the book, people started to call and say, ‘Hey, we’ve got this case in the Supreme Court. Would you be willing to do it?’ I had some early successes. One involved agricultural herbicides that caused crop damage, a decision that very much is still in the news with the Roundup herbicide. Another was a pharmaceutical case, Wyeth v. Levine, which involved a female guitarist whose arm had to be amputated after an intravenous drug had caused gangrene to spread down her arm from the injection site.

From those experiences, I began to focus on representing people who are traditionally underrepresented. I generally was fighting forces that I thought were too powerful and, in most instances, greedy. My representations sought to create a more balanced justice system. And so, a lot of the cases I have argued over the past twenty-five years have been against big companies on behalf of individuals or small companies. One good result begets more cases. And for people out there wondering, ‘Does it matter who the lawyers are’ or ‘Do people make a difference?’ I can tell you that creative arguments, an effective presentation, and a strong team of lawyers really can make change in the face of powerful forces.

‘Some of the best advice I got was to be true to myself’

I find myself in a period now of deep reflection and introspection about the state of our country and world. For the last ten years, I’ve been heavily involved in the democracy space, trying to understand and figure out solutions to the information disparities in the US and what they have done to our democracy. I’m also very focused on our joint venture with Univ and Pitt, which is funding the new Univ North site and offering accommodation and new study opportunities for students in both institutions. In my law practice, I’m trying to train and mentor young people and figure out ways to help them be successful.

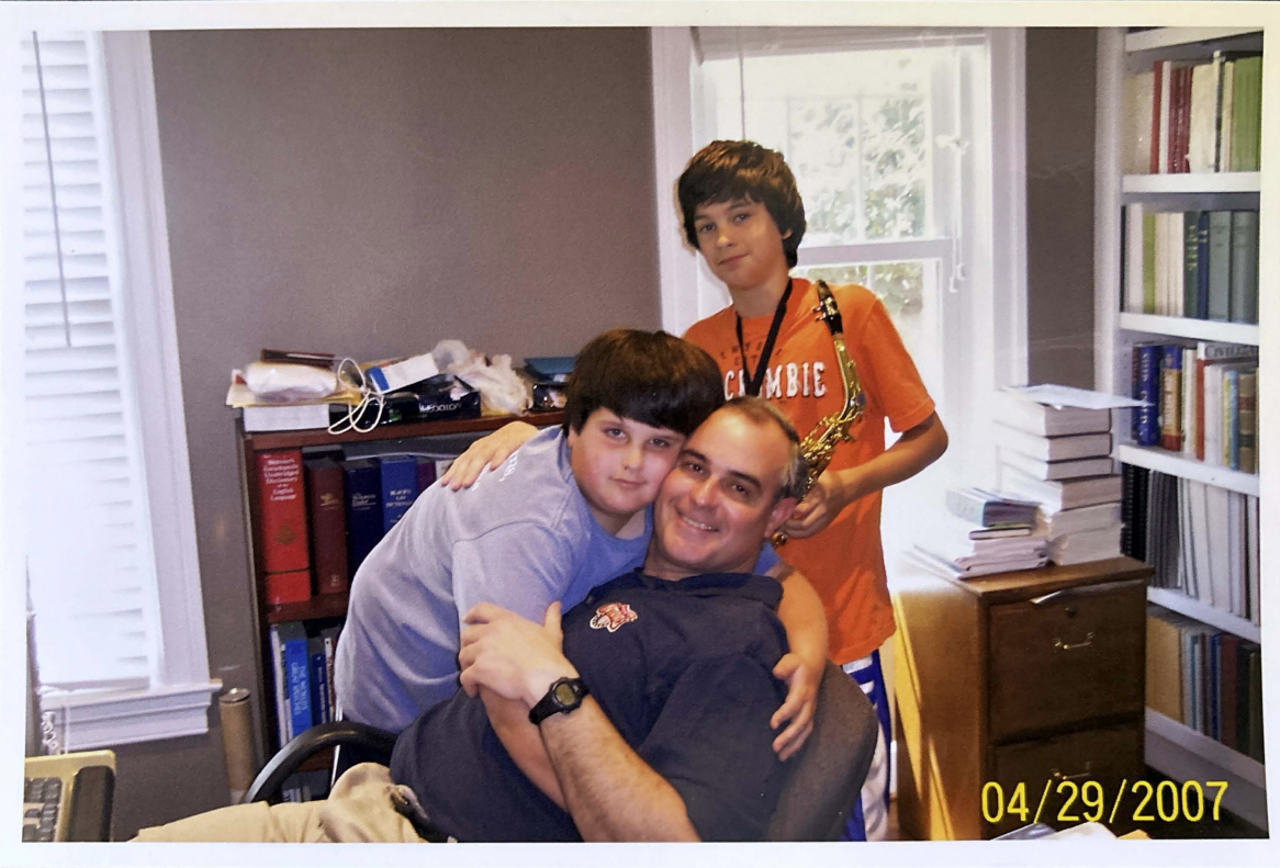

I’ve been incredibly blessed in how my life has worked out, especially with my wife, Sophie, and my children. I would also say that my friendships with other Rhodes Scholars, from across the generations, has been very important. I see a continuing desire among Rhodes Scholars to help people, and to do that in an intergenerational way that fosters friendships. I’m always hesitant to offer general advice, but I feel like some of the best advice I got was to be true to myself. I’ve had plenty of failures in my life, trying to accomplish certain things that just didn’t happen, and I’ve tried to keep looking forward after experiencing those failures and disappointments, always asking, what is the next thing that I can do that would be meaningful?