Born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1961, Dan Porterfield studied at Georgetown University before reading for a second BA in English language and literature at Oxford. He later earned his doctorate in English at The City University of New York Graduate Center while also working as a Deputy Assistant Secretary at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. From 1996-2011, Porterfield served in senior of roles at Georgetown University, including Senior Vice-President for Strategic Development and Assistant Professor of English. In 2011, he became President of Franklin & Marshall College, spearheading its Next Generation Talent Initiative through which the institution tripled the enrolment of lower-income students and became a national model for college opportunity at selective schools. Since 2018, Porterfield has been President and CEO of the Aspen Institute. He has recently published Mindset Matters: The Power of College to Activate Lifelong Growth. This narrative is excerpted and edited from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 2 October 2024.

Dan Porterfield

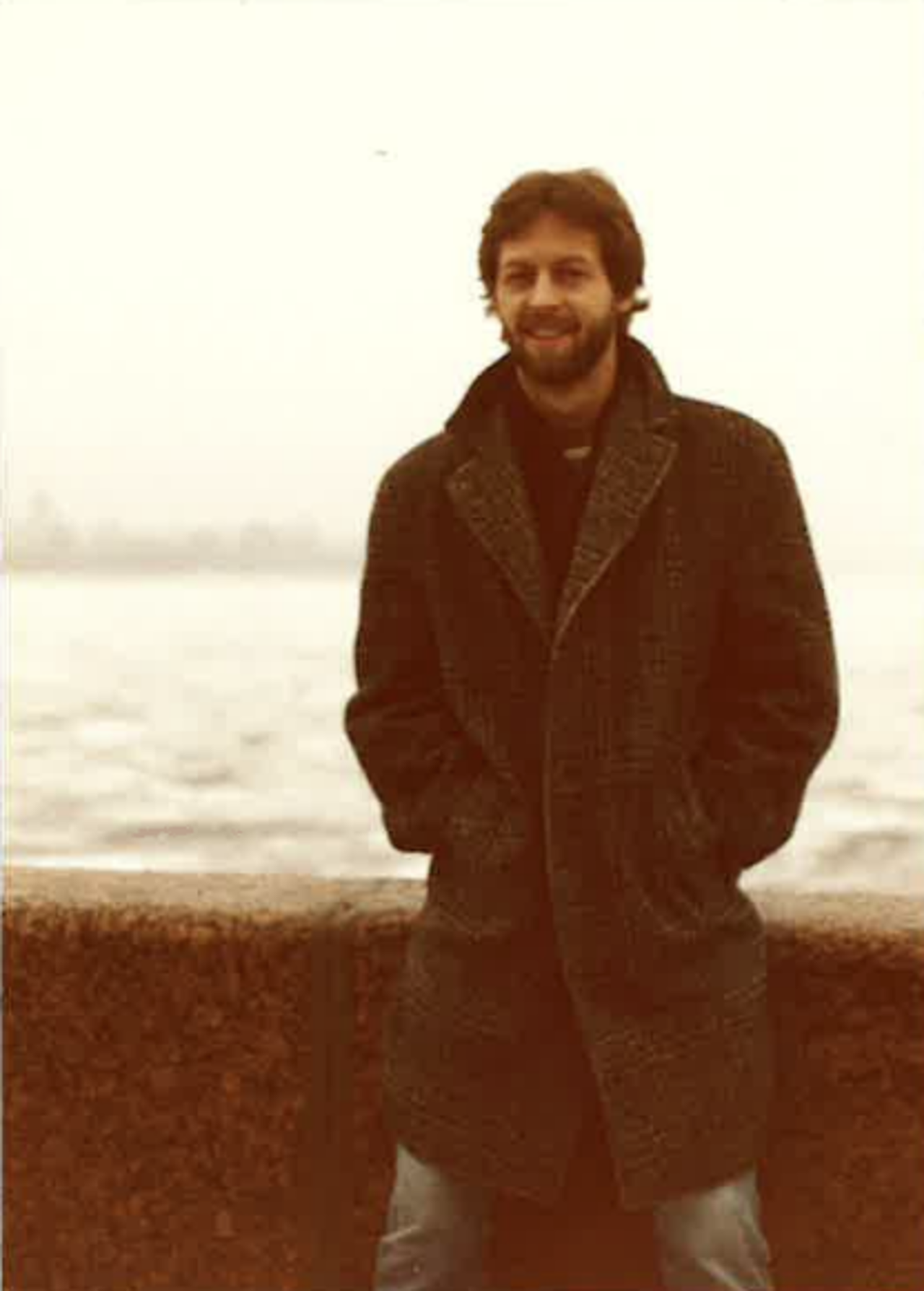

Maryland & Hertford 1984

‘The confidence to navigate other challenges’

My mother grew up in foster care and became an eminent historian of women in the American West. My dad was a playwright who taught in the Baltimore public schools for forty years. My parents met in high school, married young, and divorced around 1968. That rupture was certainly the hardest thing I’ve had to deal with, but it gave me the confidence to navigate later challenges and, more importantly, to encourage resilience and resourcefulness in others.

While raising my sister and me, my mom earned her BA in her 30’s, followed by an MA and PhD. That was a time of turmoil in the country; when our neighbourhood desegregated, I saw and lived the agonies of social conflict. White and Black kids had fistfights at school. Some on our block tried to drive out the first Black family that moved in. White flight was a real thing – many families moved away. But we made new friends, and the community came out on the other side integrated and friendly. Witnessing all this unrest as a child tore me up but also endowed me with the lifelong American hope that wrenching change can sometimes become productive.

In the 70’s, Baltimore’s school system deteriorated to the point where children could only be educated on half-day shifts. So, for seventh grade, my mother managed to get me into a private boy’s school, St. Paul’s, with a scholarship. Everything was different: the preppy clothes, activities like ballroom dance class that some kids did on weekends, the sheer difficulty of the classes. My number one, two, and three interests were sports – but even that was different, because where I grew up no one played lacrosse or tennis.

After three years, my mom let me transfer to Loyola High School Blakefield, a Jesuit school that exposed me to ideals of spirituality and community and justice, a whole outlook through which I could see myself acting on the world and not just enduring whatever came my way. After my family, my Jesuit education is the single greatest gift in my life. Home is where I learned to want love in my life; from high school and college I learned to want learning, faith, and freedom.

The poise and purpose with which I try to live came from the indelible experiences and role models enabled by Jesuits’ 500-year-old tradition of ‘helping souls.’ For example, for four years starting in 10th grade, Loyola made it possible for me to coach about ten boys and girls youth basketball teams, each of which included Black and White players who lived in different worlds and wanted to win games together. I threw myself into coaching, and into how we think when we’re trying to draw in and draw out others, an ethic of care, which propelled me into a lifetime of teaching and mentoring.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

The crossroads decision I faced upon finishing high school was whether to keep coaching basketball in Baltimore or let it go so I could enter the unknown at Georgetown. My mom always told me that you can’t know who you might meet or what you might become unless you venture out of your comfort zone. If she learned that growing up in a foster home full of children, I told myself, I could take the same approach. At Georgetown, I was a decent student, but my real priority was campus leadership and founding a program that let students mentor court-supervised youth as they navigated dangerous streets and a neglectful juvenile justice system. And I invested myself in these ways believing that following my heart through community service was exactly what Georgetown’s Jesuits wanted for me.

Senior year, I did decide to study just a bit, largely due to the president of Georgetown, the eminent Fr. Tim Healy, S.J., who once asked me, more gently than it may sound, ‘Why don’t you figure out what your brain can actually do?’ It was quite the prompt. Fr. Healy, who’d earned his D.Phil at Oxford, encouraged me to compete for a Rhodes Scholarship, but first, I went on a post-graduate service program in Nicaragua, organized by the Jesuits. I lived with a family and saw extreme poverty, and yet I also witnessed how some people’s hope could transcend their deprivations, which included, in this case, the impacts of the Sandinista/Contra war. Back home to interview for the Scholarship, I remember saying that I hoped to blend love, learning and service throughout my life. And I remember feeling that there was more than a little good luck for me in the whole process.

‘Oxford was a gift’

Reading for a second BA in English, I studied far harder at Oxford than I had before. Fr. Healy visited a couple times and found it amusing that I now knew where the library was. My tutors and undergraduate friends at Hertford College were so talented. I just hoped it would rub off.

Outside of studying, in 1985 a circle of 50-60 American and British students from across the University formed the group, Students for Peace in Nicaragua. After a village was destroyed by a marauding band of Contras, we held a week-long sponsored fast to raise donations so that the people could rebuild their lives, and later the Canadian Rhodes Scholar Craig Scott (Maritimes & St John's 1984) delivered the funds. Our members had many ideas about how to proceed, and we learned the art of compromise. I also took part in a group that included gifted writers like Elizabeth Kiss (Virginia & Balliol 1983), Brian Greene (New York & Magdalen 1984), and Michele Flournoy that met every few weeks to share drafts in a spirit of friendship and experimentation.

What great good fortune to make lasting friendships in the Rhodes community and beyond it. So many of us revelled in that chance to grow and give together, without necessarily having to over-achieve.

‘Leadership by engagement’

When I came back to Washington, DC, I was given the chance to teach in D.C.’s Lorton Reformatory and re-establish the youth program I’d created as an undergraduate. One Saturday at a book fair I ran into one of my Rhodes interviewers who said, ‘We didn’t pick you as a Rhodes Scholar to teach in prisons. You’re supposed to be leading institutions.’

Her comment hurt at first but it ultimately it helped me as a prod to try my best to make free choices based on who I truly want to be or become, and not to try to bend myself towards – or against – credentialling labels like ‘Rhodes Scholar’ or ‘Georgetown graduate.’

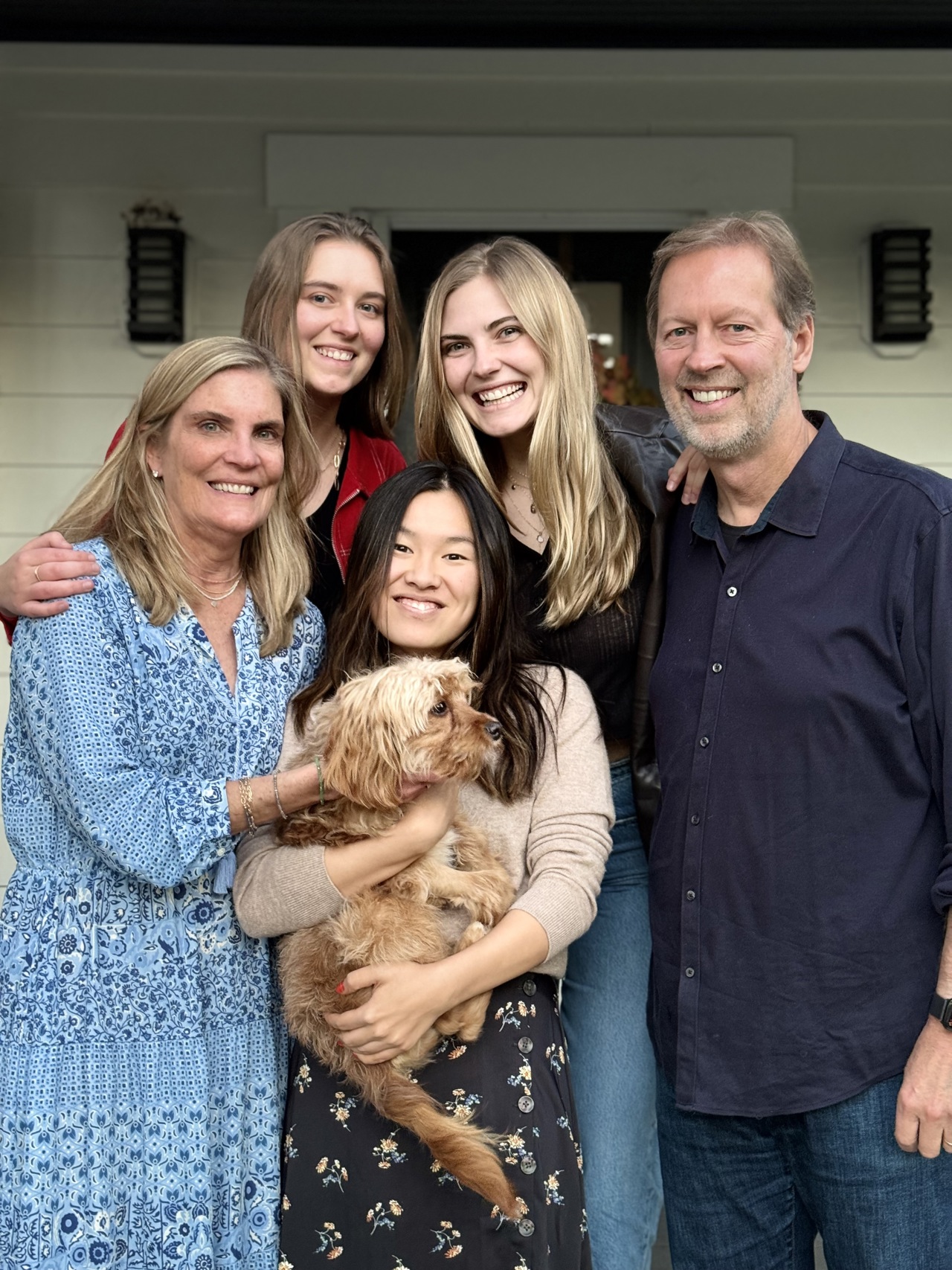

I went on to The City University of New York Graduate Center to pursue a PhD in English on writing in captivity, and how literature can create terms of freedom for incarcerated or oppressed people. I also worked part-time with the CUNY chancellor, Ann Reynolds. That led, via my close friend Kevin Thurm (New York & Pembroke 1984) to my working as a staff member for Donna Shalala, who served as the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services during the Clinton administration. After that, I taught and helped lead strategy for two presidents of Georgetown for 14 years – even living on campus with our family for eight years – before serving as president of Franklin & Marshall College from 2011-18. To me all those college roles were about building opportunity-rich ecosystems so people can develop themselves and help others.

Whether through coaching youth or mentoring immigrant children or teaching undergraduates, I’ve been privileged to be present to moments of tremendous growth and joy in younger people and, with that, on occasion, defining moments of tumult and loss and recovery. If I have anything distinctive to offer as an institutional leader, it’s that those experiences of the heart inspire me to match the spirit of my students and colleagues. I think of this as leadership by engagement.

At Franklin & Marshall, I loved immersing myself in a community of 2,400 high-striving students and serious educators. We developed a strategy to triple our financial aid budget and thereby triple our enrolment of first-generation and low-income students, which made us an even stronger school. That initiative gave me the chance to partner with Mayor Mike Bloomberg, his Bloomberg Philanthropies team, and some fellow presidents, including Chris Eisgruber (Oregon & University 1983) to create the American Talent Initiative, through which, since 2016, 140 top colleges and universities have increased their enrolment of lower-income undergraduates by more than 30,000 students.

The Aspen Institute, where I work now, is an influential people-serving institution with global reach. Founded in 1949, and led brilliantly from 2004-2018 by Walter Isaacson (Louisiana & Pembroke 1974), we work to ignite human potential to build understanding and to promote new possibilities for a better world. We have about 60 programs that develop leaders, engage youth, and solve practical problems – including 13 partner Aspen Institutes in countries like England, India, and Ukraine. We can move a little faster than a university, and we have a wide span of partners, from companies to businesses to higher education. We work on the ground in many communities, but also at the levels of structures and ideas.

‘We have to give Scholars the freedom of their own choices’

I think it’s important that the Rhodes Scholar network think of itself as an ecosystem that evolves to meet new times and include new perspectives, and to be ever more creative in how we help improve the human condition. I love the way that our recent Warden Elizabeth Kiss expanded offerings and connections for Scholars while setting a deeply respectful and engaging tone. She reminds us that Scholars’ interior freedom must be supported by this experience and not narrowed or thwarted by it.

I hope that one of the ways the Aspen Institute can partner with the Rhodes Scholars of tomorrow is by offering new avenues for connection, learning, service, and leadership. All of us can make a difference, and each of us should try.