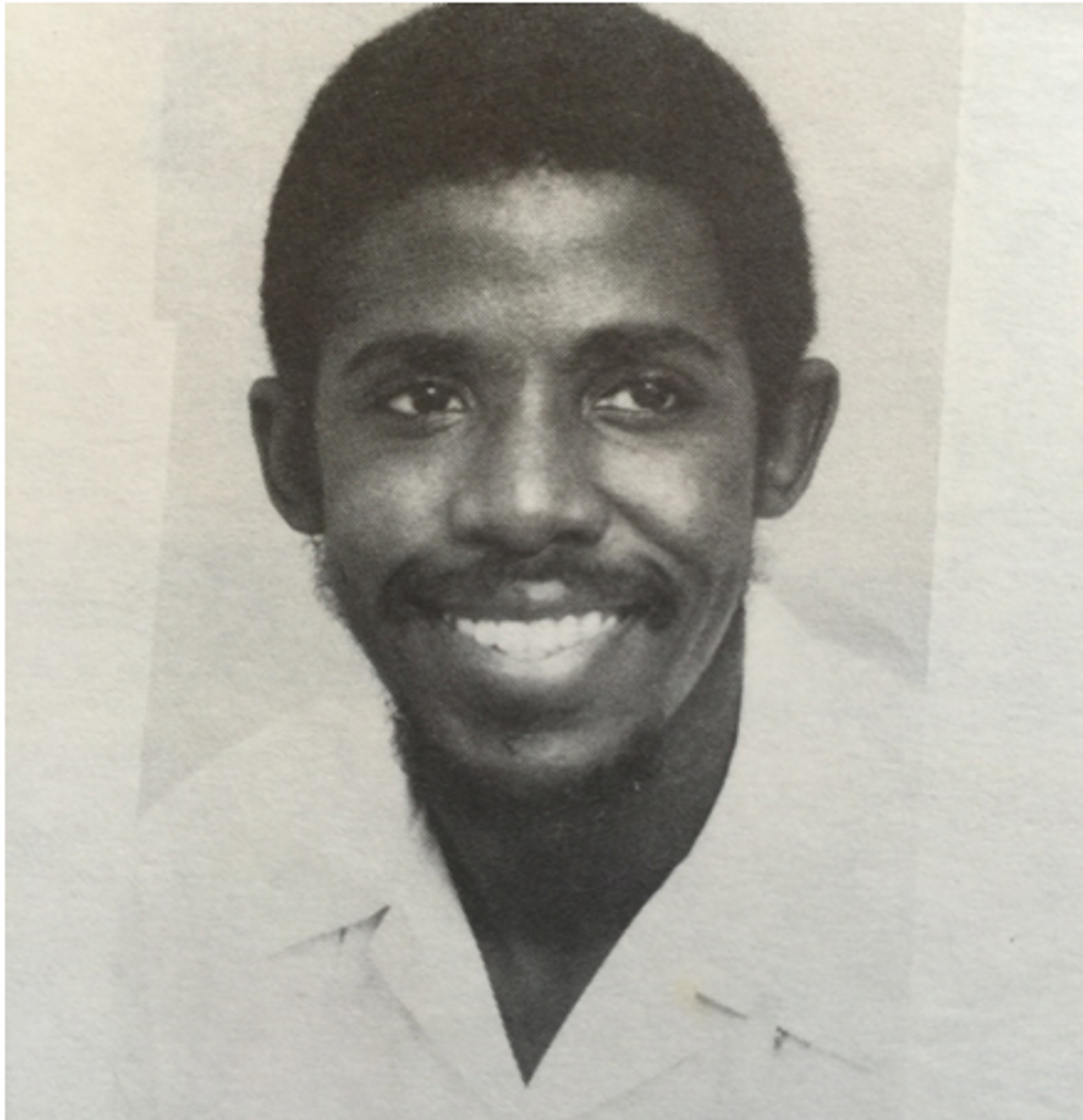

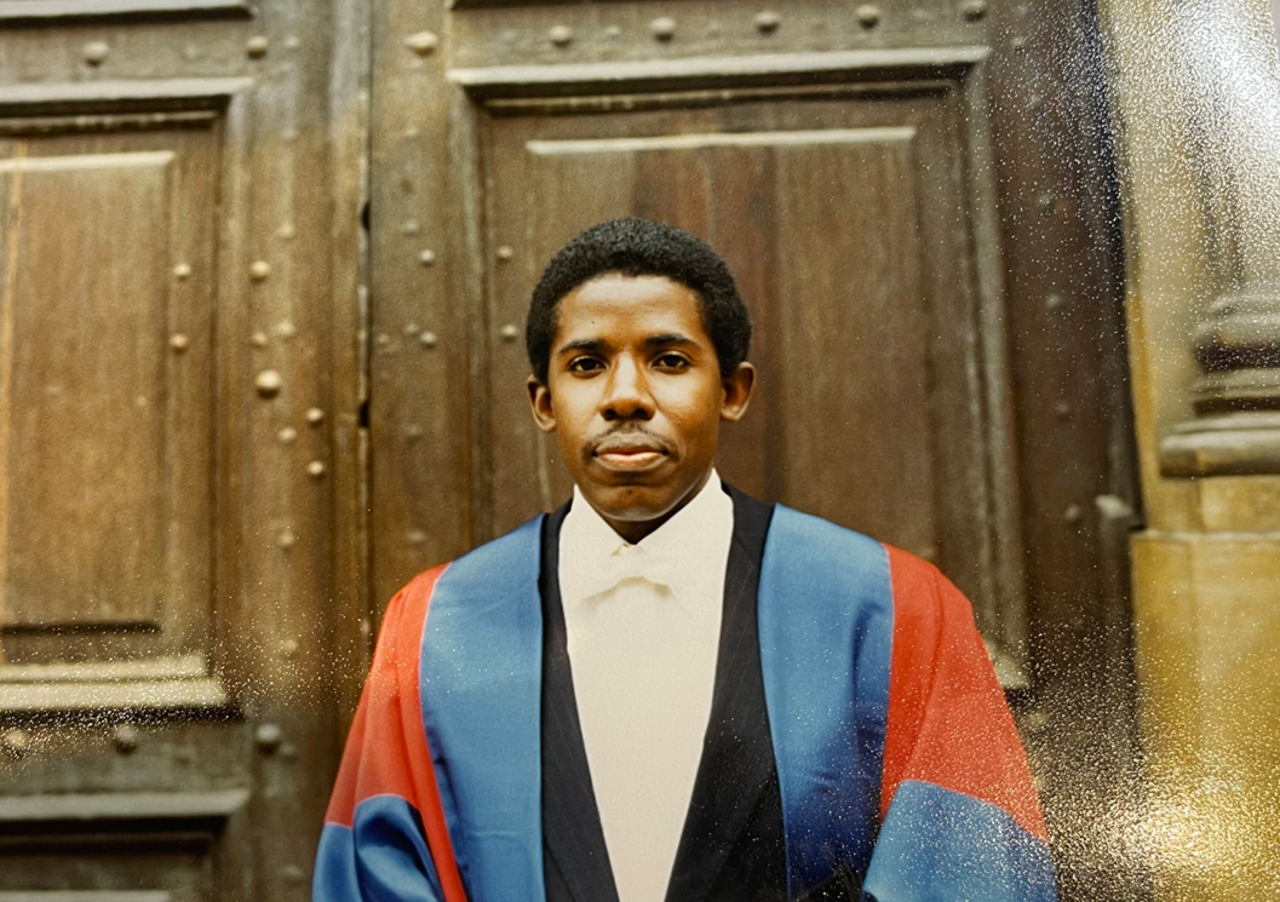

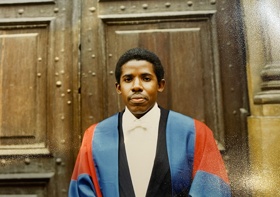

Born in Jamaica in 1962, Evan Dale Abel studied medicine at the University of the West Indies before coming to Oxford to take his DPhil in physiology. He then moved to the US, completing his residency in internal medicine at Northwestern University and taking up a fellowship and becoming a faculty member at Harvard. Specialising in endocrinology and working on the molecular mechanisms that underpin cardiac failure in diabetes, Abel went on to be on the faculty at the University of Utah and was then appointed Chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of Iowa. In 2022, he became Chair of the Department of Medicine in the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 22 March 2024.

E. Dale Abel

Jamaica & Green 1986

‘It was just very clear to us what the value of education was’

I was born in the year that Jamaica became an independent country, so my early childhood was really framed in immediate post-colonial Jamaica. Both my parents were elementary school teachers from large families and our grandparents were subsistence farmers. Our parents never forced us to do our homework or anything like that, but, with both of them being educators, it was just very clear to us what the value of education was. And I have to say they did tell me and my siblings as we were growing up that we were all going to be either lawyers, doctors or engineers. In fact, of the five of us, three are doctors and two engineers, so my parents are quite proud!

I went to one of the oldest schools on the islands, a grammar school, and I did very well there. I don’t remember a time when I didn’t want to be a doctor, so when the time came to choose which ‘track’ we wanted to be on in school, I focused on science. As a child, I suffered quite badly from asthma, so I wasn’t athletic, but I did have other interests. I wrote poetry and I also sang in our school choir. I went on to sing in a national choir which performed at state occasions, and I have a wonderfully vivid memory of being at a heads of state conference when Harry Belafonte was there too. We actually sang back-up for him, which was really cool.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I went on to medical school where we had a very clinical, classic kind of bedside medical education. That was fine, but to my mind, there was a piece that was missing, which was, how do we actually come to generate new knowledge? That triggered my interest in wanting to do more formal training in research, and that was really my primary motivation to apply for the Rhodes. We always knew about Rhodes Scholarships growing up, and there were quite a few Rhodes Scholars who had come from my grammar school.

I was academically very well qualified – in fact, when I finished by Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery degree, they had to create a whole new classification for me, ‘Honours with Distinction’, rather than just ‘Honours’, because I had got a distinction on almost every final examination. Even so, I certainly didn’t apply for the Scholarship thinking, ‘Oh, I’m going to get it.’ I was just grateful to be a finalist, and I had a firm plan B that if I didn’t get the Scholarship, I would head to the US to do my residency, as my parents had recently emigrated there. Once I did get it, I found lots of other Rhodes Scholars coming out of the woodwork to introduce themselves, and it became very clear that this was a network of people who were highly influential.

‘The DPhil experience was one that really pushed me to be independent’

I flew to London via New York, where my parents were living by then, and in London, I met some of my family members whom I’d never met before. In fact, it was my uncle who drove me up to Oxford. I remember that it was grey, and as it was getting towards October, the days were beginning to get short, too, so that was interesting. There was a small community of people who really helped orient me to life in Oxford, including Peter Goldson (Jamaica & St John’s 1985), whom I’d known in Jamaica.

I remember going up to the John Radcliffe Hospital to meet my DPhil supervisor, and he was extremely supportive. He set me up with a colleague of his who was working on diabetes. It soon became clear to me that I would have to be a self-starter and go and learn lots of new things, but I was introduced to mentors who very generous and who took me under their wing. We set up a project screening employees at the automobile factories around Oxford for high blood pressure and then enrolling volunteers from that so that we could bring them in and do tests to determine their glucose disposal rates and insulin sensitivity. I really enjoyed the work, even though it was sometimes lonely, and it certainly stretched me.

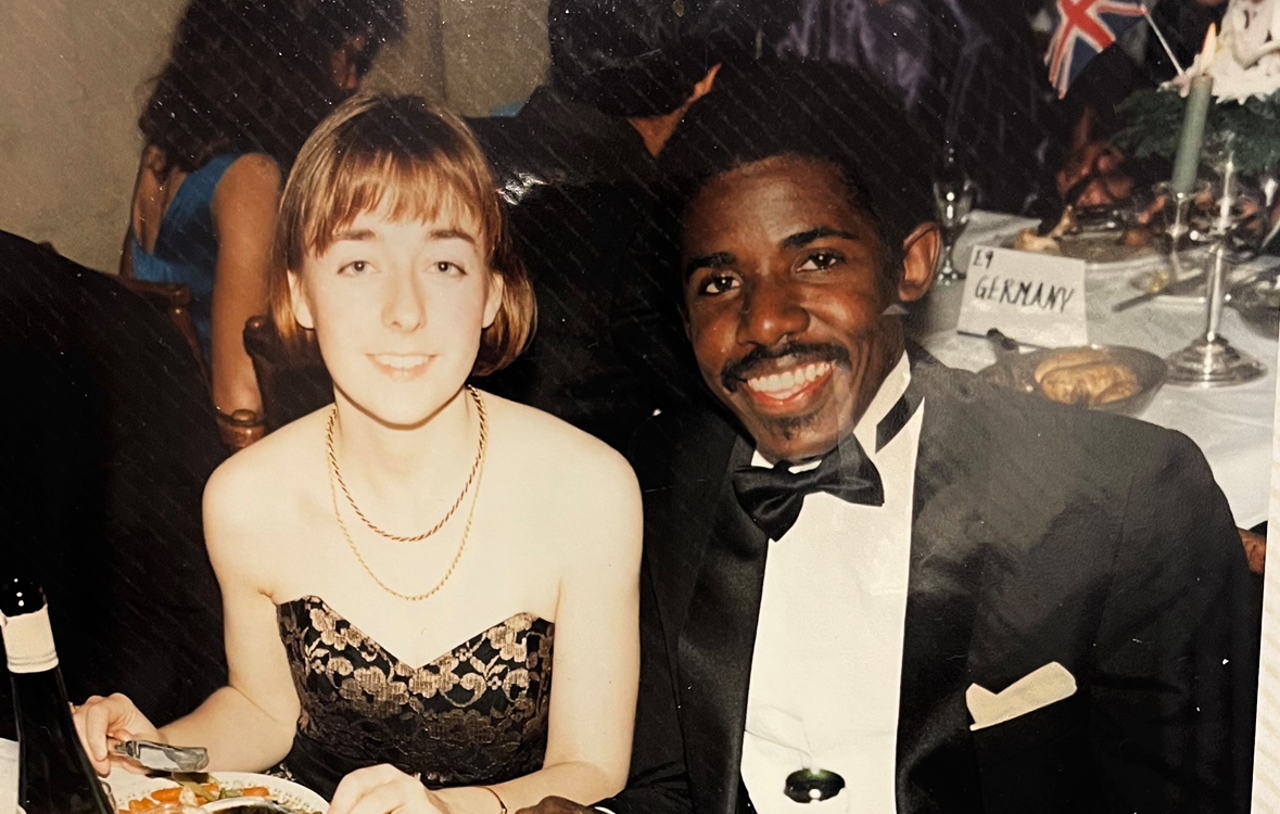

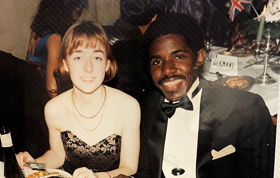

While I was in Oxford I also carried on singing and, in fact, I joined up with a group of American Rhodes Scholars who formed the Oxford Gospel Choir, so that was a lot of fun. I also met my wife when I was there. She went to the same church that I went to, and we’ve now been married for 35 years. So, Oxford was a very formative experience for me.

Going to the US to take up my residency at Northwestern gave me the chance to pursue my research while also keeping up my clinical skills. Again, I was lucky enough to have very strong mentors to guide me, and I eventually found myself in Harvard where I won a fellowship from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation which gave grants to promising people from groups who were historically underrepresented in medicine in the US. The support I gained through that was invaluable, and it allowed me to start a really high-risk project. Luckily, it worked, and along the way, I decided that I wanted to do research on interaction between metabolism and heart disease, which is where a lot of my subsequent work has been focused. After Harvard, I went to the University of Utah and then on to the University of Iowa, before coming to UCLA. I chose those opportunities because what mattered to me was to have the freedom I needed to do the work that was important to me. For me, success was about leaving a place better than I found it.

‘The importance of paying forward’

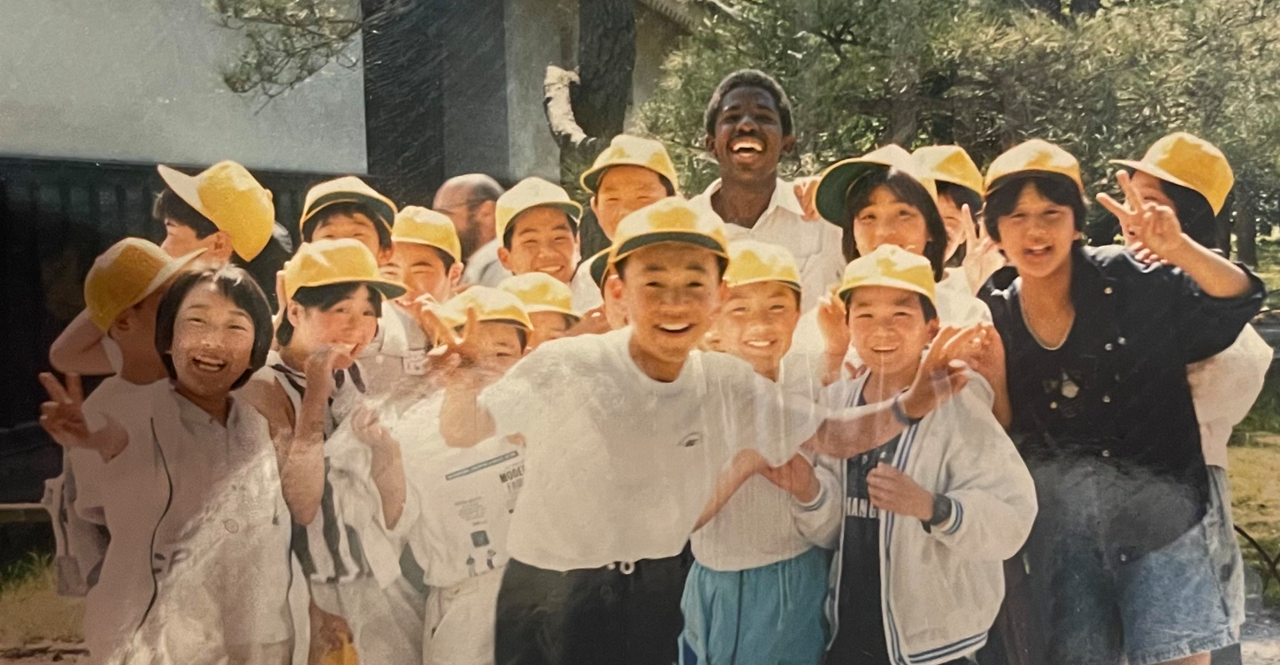

I do feel very strongly the importance of paying forward. I have been incredibly blessed and privileged to have had the journey that I have had. If you look at medicine in the US and even just at the biomedical community, it is still incredibly non-diverse. The way to fix that is to provide mentorship to individuals who are coming from backgrounds which are historically underrepresented in biomedicine. For 13 years now, I’ve led a programme, funded by the National Institute of Health, which seeks to empower early career individuals with the skills to succeed in their academic journey. We focus our work around the critical transition points, namely from graduate school to postdoc, from postdoc to faculty, and from faculty to tenure, and a lot of the work we do is on soft skills. We have probably mentored around 225 people through this programme, and it’s been remarkable to watch their careers fly.

I’m very sensitive to the fact that our success is ultimately measured by the success of those who come along behind us. I think there are probably plenty of successful people who don’t think about this and who only focus on their own success. In my mind, I think that actually represents a failure, to a certain extent. It may cost you a little bit of your own lustre or shine to devote the time and effort it takes to ensure that those who come after you ultimately succeed, but that is more than worth it. I’m very focused on ensuring that, over time, the face of academic medicine will much more closely reflect the diversity of the communities that we serve.

‘This is a community that really believes in community’

I would say that, as a community, Rhodes Scholars are amongst the most privileged individuals on the planet. To today’s Scholars, I would say, never, ever let that go to your head. You know, all of us really got here on the shoulders of many people, whether it’s our family, our friends, our teachers or our mentors. When I became a Rhodes Scholar, I saw that this is a community that really believes in community, and all of us have the opportunity to feel the benefits of the relationships and experiences that come with that.

If you have ‘Rhodes Scholar’ by your name, it opens doors. Even though Rhodes Scholars are some of the most accomplished people on the planet, I would encourage all Scholars never to lose sight of the fact that the Scholarship is a gift and a tremendous privilege. View it as something that you should really leverage in order to have a bigger impact on as many people as possible.