Born in the Baltimore area of Maryland in 1981, Cyrus Habib studied at Columbia before going to Oxford to take an MLitt in comparative literature. He returned to the US and received his JD from Yale Law School, then practising law before eventually being elected lieutenant governor of Washington State, at that time the youngest Democrat in statewide office. In 2020, Habib stepped away from politics and began his formation as a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is currently working for the Jesuit Justice and Ecology Network in Africa. Habib is also the co-founder of several youth leadership programs that still operate in Washington State. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 20 November 2024.

Cyrus Habib

Washington & St John’s 2003

‘My parents did an amazing job of not allowing their fear to become my fear’

My parents had immigrated to the United States from Iran. My father came first, to study engineering, and then my mother joined him at the outbreak of the revolution in Iran. They got married in 1980 and I was born a year later. We lived in a wonderful community, but it was a difficult time for us. For one thing, my parents were living thousands of miles away from the home that they knew. But the other thing that made it quite difficult was that shortly after I was born, I was diagnosed with a rare childhood eye cancer. It ended up taking my eyesight in my left eye by the time I was two years old and then it came back several years later, leaving me fully blind at eight years old.

There’s no good time to become blind, but what was good was that I was old enough to have some visual memories, of faces, of cityscapes and so on, but also young enough that I was still adaptable. Learning new things, like braille and using a cane, just came naturally. I also had some really influential teachers who believed in me and who were sophisticated enough and sensitive enough to strike the right balance. My parents did an amazing job of not allowing their fear to become my fear. I remember my school was nervous about letting me play on the swings and jungle gym, and my mom went to the principal’s office and said, ‘He’ll learn it differently, but he’s going to learn his way around just as well as any other kid at your school. It may happen that he may slip and fall, and he may even slip and fall and break his arm. I could fix a broken arm. I can never fix a broken spirit.’ That was the moment I learned that I deserved to be included. That was also not long after my father had been diagnosed with cancer. He survived, thank God, and my mom was the rock who took care of us both.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

At Columbia, I wanted to create a new persona. Academically, I was determined to be excellent, to outperform, to be the best, and I was pretty extreme during those years in college. This might surprise people who wouldn’t expect this of a Rhodes Scholar, but I was a big partier, including a lot of drinking, drug experimentation of all kinds, dating lots of different women during those years. Now, what I can recognise is, I didn’t want to be thought of as blind. I wanted to be as far as possible from whatever image I had of disability. There was definitely a lot of darkness that I was working through.

Academically, I fell in love with modernist literature and became an English major. Then, a week into my junior year, 9/11 happened, and it had a massive effect on me. I ended doing a double major, focusing on English and comparative literature but also on Middle Eastern languages and cultures. Edward Said was a huge influence on me, and I became involved in the pro-Palestinian movement and the anti-war movement in the lead-up to the US-led invasion of Iraq. Alongside my studies, I was also lucky enough to intern for Senator Maria Cantwell and then for the newly elected Senator Hillary Clinton.

It was Kathleen McDermott, an amazing dean at Columbia who sadly died a few years after I graduated, who approached me and suggested I should apply for a Truman Scholarship. I did that, and I was successful, and part of the experience was to go to Missouri, where Harry Truman was from, and meet Louis Blair, the executive secretary of the Truman scholarship. He was the one who said, ‘Well, Cyrus, have you thought about studying at Oxford on a Rhodes or a Marshall?’ Until then, studying in the UK had just not been on my radar, and I wasn’t convinced, but I did apply, and the interviews were a wonderful experience. Finding out I’d won was a totally macabre experience because of all the other wonderful people I’d met at the interviews who didn’t win, but it was still a very special moment I’ll remember for the rest of my life.

‘The stillness and silence allowed me to be alone with myself’

I’m not someone who ordinarily thinks in terms of regret, and Oxford brought me so many gifts and blessings, but the mistake I made was that it didn’t really make sense to do my kind of comparative literature work there. The English department at Oxford was still quite traditional then and there was no ability to do literature across continental and cultural divides. I won’t put all the blame on Oxford, and I had a great supervisor, but my interest level just wasn’t there. Eventually, I switched to an MLitt from a doctorate, writing on vision and visuality in Ralph Ellison and Salman Rushdie, and I’m still really proud that I did that piece of work.

I ended up focusing on travel, spending a lot of time in London and making friends there, and I think I probably visited two to three dozen countries during my three years at Oxford. It was also during that time that I began my conversion to Catholicism. I was what I would call a secular humanist, and I had been brought up to believe that God exists, but my family was not a part of any faith community. When my friends Andrew Serazin (Ohio & Balliol 2003) and Jacob Foster (Virginia & Balliol 2003) suggested I should go to Mass with them at Blackfriars, the Dominican community in Oxford, I thought, ‘Why would I want to?’ But I did go, and there was just a way in which the stillness and silence of that very simple liturgical experience allowed me to be alone with myself or, as I would later come to believe, alone with God, in a way that I realised I really needed.

‘I decided I’d rather be happy than successful’

I went on to Yale from Oxford, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I had helped my mom in her campaign to become a judge and I’d always been interested in politics growing up. I thought, ‘You know what? I could do this.’ In 2012, I ran for the State House of Representatives in Washington State and won, then I ran for the State Senate, and then for lieutenant governor of the state. It was an amazing experience, and I’m especially proud of the legislation we introduced guaranteeing paid sick leave for almost all Washingtonians for the first time.

Why did I leave it all behind? The most pithy answer I can give is that I decided I’d rather be happy than successful. My father was diagnosed with cancer again in 2013 and he passed away in 2016. I began to realise I had this addiction to achieving things and moving up, and it was never enough. Then, in 2018, I was also diagnosed with cancer. It was caught early and treated, but it gave me the opportunity to see that there was a deep inauthenticity in the way I was living. That’s when I started to explore living a simpler life, still dedicated to public service, but in a much smaller and more humble way, and, in 2020, I became a Jesuit.

‘It’s important to identify what you believe’

20 years ago, I was in Oxford, and I was at the very, very beginning of having my life changed by what I found there. There are so many graces and gifts waiting for us whenever we set out on a mission or an adventure, and the Rhodes Scholarship is a very rich one. I just want to express my gratitude for all those gifts and to everyone at the Rhodes Trust who makes this opportunity available and is working to expand it.

To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say that it’s important to identify what you believe – not what you know, but what you truly believe – by taking social and philosophical and moral and theological questions seriously. I’m not saying that anyone needs to choose what I’ve chosen, but once you’ve found what you believe, commit yourself to it as best you can by trying to live authentically according to that way of being. None of us is perfect, but at least you’ll have a North Star to look to. I think, if you do that, you’re going to have a good night’s sleep more often than you won’t.

Transcript

Transcript

Interviewee: Cyrus Habib (Washington & St John’s 2003) [hereafter ‘CH’]

Moderator: Celia Tezel [hereafter ‘CT’]

Date of interview: 20 November 2024

[file begins 00:01]

CT: We’ll just check everything is good. Great. Okay, so, my name is Celia Tezel, a member of the Global Engagement Team at the Rhodes Trust, and I’m here with Cyrus Habib, Rhodes Scholar from Washington and St John’s 2003 on 20 November 2024. Cyrus is helping us launch the first ever Rhodes Scholar oral history project and we’re very grateful to you, Cyrus, for this gift to the community.

CH: Thank you so much.

CT: So I’m going to start with a few formalities, and we’ll get into it. So, can you please state your full name for the recording?

CH: Yes. My name is Cyrus Habib.

CT: And do I have permission to record this interview?

CH: You do have permission. Thank you.

CT: Great. So, I want to start by going back to the very beginning. Where and when were you born?

CH: I was born in the Baltimore area, in Maryland, in August of 1981.

CT: And what was it like growing up in Baltimore?

CH: It was really nice. My parents had immigrated to the United States from Iran. My father had first come in 1970 to study at the University of Washington, where he studied engineering at the undergraduate and graduate level, and then my mother had to come over at the outbreak of the revolution in Iran, and so, she moved to Maryland. My parents had been engaged and then gotten married. So, she ended up joining him in Maryland in 1980. I was born a year later and, it was a wonderful community. It was a difficult time for us. I mean, for one thing, my parents were living thousands of miles away from the home that they knew, in particular for my mom who had recently moved to the US.

But the other thing that made it quite difficult was that shortly after I was born, I was diagnosed with a rare childhood eye cancer, and it was diagnosed in my left eye, and it ended up taking my eyesight by the time I was two years old in my left eye, and then it came back several years later, leaving me blind in my right eye at age eight years old. So, it was a challenging time. My parents did an amazing job of not allowing their fear to become my fear, and so, I did have a very pleasant childhood, but that context is important.

CT: Wow. I mean, and such an early age as well, to lose your eyesight. When you look back at those formative years, especially when you’re going through such a massive challenge medically and also just looking into the future, what was it like in your school in your school, with your friends, and going through this period of going blind?

CH: Yes. Well, when I was in politics and I would talk about this, I would often joke that I became blind at age eight, and since I was born in 1981, that means that I became blind in 1989, and all eight years I could see took place in the 1980s. So, all my visual memories are still from the 1980s, and so, everyone still looks like Cyndi Lauper and Boy George. By the way, that joke got fewer and fewer laughs as the audience became younger and, kind of, ceased to know who Cyndi Lauper and Boy George are. But there’s a truth behind that humour, which is that my parents did everything they could, including making sure that I received treatments, chemotherapy and radiation to try and extend my eyesight, because they knew that those early years would allow me to form a, kind of, archive that would serve me for the rest of my life. And while I didn’t get to see everything, and being sick, I didn’t get to travel the world and build up a registry of, like, the pyramids and the Coliseum, or whatever, but I did get to see faces and cityscapes and all these things, and so, that has been really helpful to me over the years, just those memories. And while there’s no good time to become blind, I think the nice thing about that particular age is that I was old enough that I could have some of those memories, but young enough that I was still adaptable, you know? And so, as I needed to learn Braille and how to use a cane and all the different adaptive technologies that are out there, I was young enough that learning new things just came naturally.

CT: Yes. That’s really powerful, actually. And you talk about being adaptive to this situation: what did your community look like outside of your family? You’ve said that your family was really supportive, and I love the comment about them not putting their fears onto you.

CH: Yes.

CT: I think that’s really special. But what was it like growing up with people outside of your family?

CH: Yes. I had some really good friends and some really influential teachers who believed in me, who were sophisticated enough and sensitive enough to strike the right balance. You don’t want to be insensitive or fail to provide accommodations and, at the same time, you don’t want to go overboard and become overly protective. And there’s a story that I like to tell that, kind of, illustrates that, which is that shortly after I’d become blind, I was in third grade and, like every third grader, my favourite time of the school day was recess when all the kids would go out, even in rainy Seattle, and play on the playground and go up on the slides and the swing sets and the jungle gym and play. And the school, knowing that I’d recently become blind, was not thrilled about this kid, playing five feet off the ground. I think it also didn’t help that they knew my mother was a litigator. So, while the other kids were playing, they would keep me with the recess monitors and the teachers on the sidelines by the school building. And after this happened a few times, I went home and told my parents that I was being excluded, and what was happening, and my mom went to the school the next day, and she went to the principal’s office and, importantly, she took me with her to the principal’s office so that I could learn how to be an advocate for myself, and she said to the principal, ‘I’m going to take my son to your school on the weekend and I’m going to teach him how to get around the playground and the swings and the jungle gym and the monkey bars and all these things, and he’s going to learn it. He’ll learn it differently, but he’s going to learn his way around just as well as any other kid at your school.’ And then she said, ‘It may happen that he may slip and fall, and he may even slip and fall and break his arm.’ She said, ‘You know, that’s a fear that any mother has.’ But then said, ‘I could fix a broken arm. I can never fix a broken spirit.’

CT: Wow.

CH: And so, I share that story because it was the moment-, and I was, like, eight years old, but it was the moment when I learned that I deserved to be included, that I deserved to belong and that, somehow, being excluded was an injustice, and it’s also when I had my first experience of advocacy, something that would go on to play a really important role in my life.

CT: Wow. I mean, it sounds like your mother was a really influential figure for you in putting you on the path that you then continued on. Can you talk a little bit more about your mother?

CH: Yes. I mean, both of my parents- I marvel at this, because, look, at the age at which Rhodes Scholars head off to Oxford, which is to say, 22 or 23 – now, of course, there’s a wider window, but for most it’s at that age, 23 – my mother had me in a new country she’d only lived in for year, speaking a language that [10:00] was her third language. My father was 28 years old. And then, a few months later, they heard the words, ‘Your son has cancer.’ And then, a couple of years after that, my father was diagnosed with cancer. And so, there was this time when my mother, who had just started her studies at the University of Maryland Law School, would be, kind of, shuttling from one hospital room to another to see my father, who was being treated, and to see me, and it was just the three of us. But this was an extraordinarily difficult thing for both of my parents, but my mom was the rock, because she was the one who had the good health to, kind of, take care of us. And fortunately, thanks be to God, my father survived that bout of cancer, as, obviously, did I. But then at the age of 30, 31, to know that your son is going to be blind for the rest of his life, most likely.

CT: Yes.

CH: It’s just an extraordinarily difficult set of things to happen at that age, with no real-, I mean, it’s not that they had no extended social network. They did, but their families weren’t there, their siblings weren’t there in Maryland, their parents weren’t there. I can only imagine how difficult it was, and I’m so grateful that they somehow had the resilience and the resourcefulness to raise me in a way where they never put pressure on me, but they also never limited with lowered expectations either.

CT: Yes. And I think it’s a really important message of allowing accessibility without taking away that human need to be independent, and that we all deserve to feel that independence. I think that’s a really strong message and it’s amazing that your parents, who-, this was new for them as well, right? To have a son that couldn’t see. To make those decisions correctly is really powerful, actually.

CH: Sorry to interrupt. I was going to say, I think it’s something that every parent deals with, in the sense that every child is a stranger. You don’t know what their talents are going to be. You don’t know what challenges they’re going to have. And so I mean, here I am with the collar, opining on parenthood, but it does seem to me that every parent has to, kind of, figure this out. But as Andrew Solomon writes about in one of my favourite books, Far From The Tree, this is a dynamic that’s particularly vexing in the context of parents of children with disabilities, and I know that I wouldn’t be where I am, I wouldn’t have had the kind of rich life that I’ve had if my parents didn’t somehow have that grace to navigate this so skilfully, and I know it wasn’t easy for them.

CT: Yes. That’s really beautiful. You spoke a little bit about family and the importance of family and I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about where your ancestors come from and your wider family outside of your parents.

CH: Yes. So, both of my parents grew up in Iran. My mother went to Catholic school, which will become relevant later as we go along. Both of my parents were from pretty well-off families, pretty privileged families, in a lot of ways. They received really good educations and grew up during a time that was pretty happy for them. They experienced their childhood in a very joyful way and the country they grew up in, certainly, the government was not perfect at all, and I think we need to be very clear-eyed about the Shah’s regime, but they experienced it as being a time of freedom and opportunity and it was unrecognisable to them after the revolution. My father grew up in a secular Muslim family and then, as I mentioned, he came to the US to go to university. And he was, kind of, a hippy. I mean, he came to the US in 1970. And so – he passed away in 2016, which is why I’m speaking about him in the past tense – he was somebody who really loved both his Iranian culture, Persian culture and heritage, and instilled that in me, but also loved Americana. So, he was someone who could listen to the poetry of Rumi or Hafiz or our great Sufi poets and then listen to Bob Dylan and that’s just the kind of person that he was, and he passed on that love of culture and art and music and literature to me.

My mom is my inspiration to have gone to law school. She grew up watching Perry Mason episodes in Iran and from a young age wanted to be a lawyer, kind of, fell in love with the American legal system and practised law in the US and, for almost 12 years now, has been a Superior Court judge in Washington state. And so, growing up, it was the three of us – I’m an only child – it was my mom who, kind of, taught me and encouraged me to debate, and I guess they would say maybe more than debate, but even argue. And I remember a moment, growing up, when my mom said to me, ‘I think you should become a lawyer because you love arguing so much. You should probably get paid to do it.’ But the debate side of things was so important. The culture in our house was one where my parents really gave me an equal voice, or, at least, what I perceived to be an equal voice, and we talked through major decisions and it gave me a kind of boldness and a sense of responsibility at a young age.

CT: That’s great, and I’m really looking forward to talking about your professional journey into various different spaces. What was your experience like through high school and then going into your undergraduate years? Because you were at Columbia studying English, weren’t you? And then you graduated summa cum laude and then landed an internship with Senator Hillary Clinton. So, a lot happened in a short space of time, and I just wanted to talk about that transition from being a teenager to a young adult and going into university and what that experience was like

CH: Yes. Well, it’s a fraught transition for everyone, but here’s what happened. I went to a wonderful public school, a magnet school called the Bellevue International School, and it’s not an international school in the sense of having children of diplomats or anything like that. It’s called an international school because the curriculum is more global, and at that time, it was a new school. It ran from sixth through twelfth grades – it still does – and so, that’s a seven-year curriculum. And in a lot of ways it was a wonderful experience: very small class, small school, my graduating class was 36 students.

But in other ways, the problems that I entered at age 11, which was only a couple of years after I became blind, and was still very much dealing with that, trying to understand that. And when you grow up with the same cohort of kids for seven years, as you’re changing, it can feel awfully claustrophobic, because you’re maturing and yet, everyone still, kind of, remembers you. The teachers, the other parents, the students, they all, kind of, already know [20:00] you, and so, you can’t really recreate yourself, reinvent yourself. And so, this was something that I can now look back and realise how much I wanted to kind of, try on a new, more mature Cyrus, a less angry Cyrus. In fact, I didn’t go by Cyrus during those days. Cyrus is my middle name, which I chose, which is a whole other story. I’ll take a detour and just say that when I was young and growing up in Maryland, it’s such a Catholic place, everyone had middle names, but it’s not an Iranian custom to give middle names.

So, I came home and, as you can tell by now, I would complain when I felt excluded, and so, I went to my parents: ‘You know what? I don’t have a middle name.’ And they said, ‘Well, okay, if you want to have a middle name, you can have one. You can choose it. You should choose it, because we already gave you a name, so, if you want a middle name, you’ve got to pick it.’ Well, I’d heard of Cyrus the Great: obviously a huge figure in our history. I’d also heard of Alexander the Great, which wouldn’t work, because he’s such a problematic figure in our history. And so, I went with Cyrus, and Kamyar is my first name, and so, I chose Cyrus. So, maybe that speaks of a certain egotism as a child, that I was looking for a name that went with ‘the Great,’ and when I would argue with my parents later, they would joke that perhaps I should have chosen Ivan the Terrible. But that’s how I got the name Cyrus. And so, as I went into high school, one of my hobbies and then it actually even became a little bit of a professional thing, was, I played piano, and so, I started going by KC, by my initials, and I can look back now and see that that was an attempt to, kind of, rebrand and to be someone new as I was dealing with my relationship with being blind and wanting to be attractive and all those things that teenagers think about.

But, as the musical Hamilton so famously puts it, ‘In New York, you can be a new man,’ and so, it wasn’t until I went to Columbia that I started going by just Cyrus. And I should have mentioned that shortly after I became blind, we moved to Washington State, to the Seattle area, so, coming from a suburb of Seattle to live in New York City, I had this total desire to break out and be someone completely different and so, I went to extremes, as sometimes I tend to do. And this might surprise people who don’t expect this of a Rhodes Scholar, or of what would be a future Rhodes Scholar, but I was quite a big partier, including a lot of drinking, drug experimentation of all kinds, dating lots of different women during those years. And what I can recognise is, I didn’t want to be thought of as blind. I wanted to be as far from that stereotype, or whatever image I had of disability. I wanted to be as far from that as I could be, and that motivated me not only, kind of, socially to create a, kind of, persona, but also academically, to be excellent, to outperform, to be the best. And I mean, I believe that God can with even our darkest fears and anxieties and impulses. And so, a lot of good came out of all of this, but there was definitely a lot of darkness that I was working through that led me to be so, kind of, extreme during those years in college.

CT: And you speak about how you were also channelling a lot of that energy into your academic accomplishments through your undergrad. Can you talk a little bit more about what that looked like for you?

CH: Yes. So, I really loved literature and I had this amazing professor, Michael Seidel, who I had for our-Columbia has this core curriculum. So, we all talk a class called Literature Humanities or Introduction to Western Literature, and he was my professor for that. He was a Joyce scholar and I fell in love with modernist literature in particular, twentieth-century literature, and I was pretty confident that I was going to be an English major and, in fact, I was an English major. But a week into my junior year, my third year at university, 9/11 happened, and it completely changed-, I don’t want to say completely changed, but it had a massive effect on me, my sense of who I am and my academic interests.

And so, I still did the English major but I ended up doing a double major, focusing first on English and comparative literature but then also on Middle Eastern languages and cultures, and a big influence on me at that time, someone who was a towering figure not only at Columbia but in academia globally, was Edward Said. He was a professor in our English and comparative literature department, but as the most prominent Palestinian American intellectual, he also, of course, wrote very widely about the Middle East, in particular about Israel Palestine, but not only that. And so, I became very influenced at that time by the pro-Palestinian movement but also, increasingly, the anti-war movement in the lead up to the US-led invasion into Iraq, which would happen in my senior year of college. So, I found my passion, which was comparative literature, literary theory and its intersection with the Middle East. So, wrapped up with that is also postcolonial studies. You mentioned Hillary Clinton, and so, just before 9/11, the summer before 9/11, I had interned in Washington, DC for my senator, Senator Maria Cantwell, who later became a friend, and is still in the Senate, and then, based on that experience, I ended up getting an internship with newly elected Senator Hillary Clinton of New York, working in her New York City office, and my first day on that job was three days after 9/11.

CT: Wow.

CH: So, what had been planned as a, kind of, run-of-the-mill internship, licking envelopes and answering phones, instead became this experience of helping displaced New Yorkers find new office space and apartments, those who had been displaced from downtown Manhattan as a result of 9/11. And so, it gave me this upfront, front-row view of the ways in which government can help people in times of crisis. So, all this was happening, all at the same time.

CT: Wow. That’s an intense time period for all of this to be happening.

CH: Yes.

CT: And at what point in this timeline did you decide to apply to the Rhodes Scholarship?

CH: Well, what happened was that around that same time, [30:00] I was approached by an amazing dean at Columbia, an associate dean for academic affairs, who sadly died a few years after I graduated: Kathleen McDermott, rest in peace. She died of ALS. Dean McDermott knew about me because of some of my accommodation needs and some of my advocacy for myself and for others around disability issues on campus, and so, she approached me and suggested that I apply for the Truman Scholarship, and I ended up doing that and was fortunate to win the Truman Scholarship in my junior year. And Louis Blair, who was the executive secretary of the Truman Scholarship, was a towering figure and someone who really believed in, as we called them, the British fellowships. And so, I won the Truman.

Part of experience is, you go to Missouri, where Harry Truman was from, and you spend a week there, and you meet with him. And I was already getting ready to apply to law school, and I met with Mr Blair: that’s what we called him. We didn’t dare call him anything other than Mr Blair. He said to me, ‘Well, Cyrus’ – his southern accent– ‘have you thought about studying at Oxford on a Rhodes or a Marshall?’ And I said, ‘Honestly-,’ and I had no reason to hide anything at this point: I truly had not. Once I had applied for the Truman, I’d heard about these other scholarships, but I just had no interest, and, I mean, no offence to you or to anyone else, I had no interest in living in the UK. It just wasn’t on my mind, wasn’t on my radar. And he said, ‘Well, I think you ought to do it. I think you ought to apply.’ And so I wasn’t convinced and, in fact, I went on to apply to law school. But as time went on, I would just talk to people about it. I learned about what kind of doors these scholarships could open. Because of how much I fell in love with Middle Eastern studies and comparative literature, I also started thinking I wanted to do some graduate work aside from law school, and so, I thought, ‘Well, okay, this makes sense. I’ll do that and then I can come back and go to law school.’ And so, that’s ultimately what led me to apply to the Rhodes.

CT: And what was the interview process like for you?

CH: Well, back then, in the US, we had a two-tiered interview process: we had state-level interviews and then district-level interviews. I felt like the state-level interviews were much harder. I mean, maybe it’s just that it was the first time. And yes, I felt like, by the time I did the second one, I, kind of, knew who I was a little bit better with respect to this whole thing. I felt more sure-footed. One thing I remember is that I did the state interview and then I flew back to New York because-, Oh, no, I’m sorry. Let me correct that. They do tell you immediately whether you’re going on to the district interview, but it was before that. The way I found out that I’d received an interview at all, in the first place, was a voicemail that I received on my answering machine – an antiquated technology for, perhaps, any current Rhodes Scholars watching this – and the message was from Rob Mitchell (North Dakota & Merton 1974), who was the secretary of the state selection committee, and he said – I just remember this so clearly – ‘By dint of your selection as a finalist, you’re being invited to Seattle.’ And I was thrilled. I knew it was good news. Then I went to one of my suite mates and I said, ‘What does “By dint” mean?’ I’d never even heard that phrase before. And so, I was, kind of, nervous, and I later joked with him-, we ended up practising law in the same legal community in Seattle some years later and I said, ‘Rob you totally threw me off my game, because I was coming into this thing thinking I had to use expressions like “By dint” in order to be a Rhodes Scholar.’ But it was a wonderful experience. And in fact, I should say it’s too bad that we don’t have those state-level interviews, because I loved meeting the Rhodes Scholars from Washington State, many of whom I would go on to view as mentors later on.

CT: And what did it feel like when you found out you’d won the Scholarship?

CH: Well it’s a totally macabre process, or was– don’t edit that part out! But I only mean it in the sense that they line all of you up and then they tell you who won, and so you’re thrilled, of course, but you can’t act too happy, because you’re standing right next to these people who just lost, and you’ve gotten to know them, and so, you have to be somewhat circumspect, emotionally. But obviously, it was a very special moment I’ll remember for the rest of my life. And two related memories are that, once we’d said ‘Goodbye’ to all the poor finalists who had not won, a couple of whom I later met at Oxford because they came on various other scholarships-, but then we’re sitting in the conference room with the interviewers, the panel, and the four of us who had won, and one of the panellists said to us, ‘Okay, now you’ve won the Rhodes Scholarship, now it’s time to figure out what you actually want to study.’ And I was slightly scandalised, but largely amused.

The other thing is that Chesa Boudin (Illinois & St Antony’s 2003), who would go on to be my best friend in the Rhodes community, one of my best friends in the whole world, and the father of my godson, Aidan, won the Rhodes in that same year. And, his parents had been members of the Weather Underground, and so, he had this whole political history, and they were serving prison sentences at the time, and so, it was all very controversial. And so, it made the front page of the New York Times the next day, or that Sunday, that ‘Chesa Boudin, child of Kathy Boudin and David Gilbert, has won a Rhodes Scholarship.’ And at the very bottom of that story, it said, ‘Also elected were-,’ and it mentioned three people and it was, like,‘A blind photographer,’ which was how it described me, because I had done some photography, and a couple of other people. And so, 20 years later, he still holds it over me that, ‘You were, kind of, a footnote in my story,’ not that it was a story he particularly wanted to have published, because it was all about this controversy.

CT: Well, that’s definitely what best friends do.

CH: Yes, yes.

CT: And so, what was it like coming to Oxford? Can you describe a little bit about that transition period and any significant experiences [40:00] when you arrived here?

CH: Yes. I’m not someone who ordinarily thinks in terms of regret or, ‘I should have done this,’ and, my time at Oxford had so many gifts and blessings, that I’ll get into. But a mistake I think I made was that, as I mentioned earlier, I had developed this desire to do graduate study in this field of comparative literature and, it really didn’t make sense to do that degree at Oxford. Oxford was not a place that was particularly strong-, in fact, it was sceptical of the kind of literary theory that I had studied because I had studied not only with postcolonialists like Edward Said and Gayatri Spivak, but also had the privilege of studying with Jacques Derrida, the founder of deconstruction. I mean, these are towering figures. But the English department at Oxford was still a quite traditional place at that time, aside from two scholars whom I got to know, but even those two scholars were themselves students of the very people I’d studied with as an undergraduate.

So, when I went to Oxford, I first started out in the modern language department, because that’s where I thought I could do comparative work, but the thing is, I wanted to read Persian literature as well as French- and English-language literature, and each of those three, you had to do in a different department. So, you had to be in modern language to do French, English to do English, or quote unquote ‘Oriental Studies’ to do Persian. So, there was no ability to do literature across those continental or cultural divides. And so, I started out in modern languages. It wasn’t a fit. I had to apply to switch into English. Then I started out in English, to do a doctorate, and it just wasn’t a good fit. And I won’t put all the blame on Oxford. In fact, I will also say that I was much more interested at that point-, maybe because I didn’t find a good academic home, or maybe because it was a little less structured than what I needed, I ended up really focusing on travel. This is a common refrain among a lot of Rhodes Scholars, I’m sure, but, travel, spending time in London, making friends in London and, let me say again, travel. I think I probably visited two to three dozen countries during my three years at Oxford.

CT: Wow.

CH: And so, I just kept trying to write this dissertation, but my interest level wasn’t there. I didn’t feel I had – I really didn’t have – an academic community. I had the Rhodes community, but I didn’t have a community within the department that I could really, kind of, bounce ideas off. My advisor was wonderful. She really did the best she could. But all of that meant that, in the end, what I decided to do, or what I was encouraged to do, was to switch from a DPhil to a degree called an MLitt, which is only offered at a few universities: Oxford, Cambridge, maybe Durham or a couple of others. It can be a number of different things, but oftentimes it’s for cases like mine, where you start out thinking you want to write a dissertation and you either lose steam or you decide that your project is going to be slightly shorter. And so, that’s what I did. I’m still proud of that, what I wrote. I wrote on vision and visuality in The Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison and The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie.

CT: Wow. That sounds really interesting.

CH: It was, it was. But again, yes, there were a lot of other things I was focused on at that time. And so, I will say that Oxford was a deeply rewarding experience, but not, for me, a deeply rewarding academic experience.

CT: Yes. And actually, that moves me on to my next question, which is about your life outside of the academic side, because while you were in Oxford, you began your conversion to Catholicism. I wanted to expand a bit on that part of your life.

CH: Yes. In fact, as we record this, I can tell you that it was 20 years ago exactly last week that a Rhodes classmate of mine, Andrew Serazin (Ohio & Balliol 2003), and another Rhodes classmate of mine, Jacob Foster (Virginia & Balliol 2003) – Andrew is a cradle Catholic. Jacob is Episcopalian but, kind of, Anglo-Catholic, if you will, high-church Episcopalian – the two of them invited me, on 14 November – I can tell you thanks to Gmail – to attend Mass at Blackfriars, which is the Dominican college or permanent private hall at Oxford, run by the Dominican order of the Catholic Church. And I had no interest in religion. As I mentioned, I was deeply influenced by Edward Said, a secular humanist. I grew up in what I like to call a generically monotheistic household, which is to say that I was taught that God exists and God is good, but we weren’t a part of any kind of religious faith community. I suppose you could say that Islam would have been the default, but really, we didn’t practise Islam. I didn’t set foot in a mosque until I did so as a tourist, visiting Egypt as a Rhodes Scholar. But I grew up with a deep respect for all religions. Nevertheless, I had no interest in attending any kind of worship experience.

And so, when Andrew and Jacob invited me to Mass, I said, ‘What am I, crazy? Why would I want to go to a Catholic Mass?’ And Andrew said, ‘Oh, Habib, just come. There’s a lot of chanting’ – because Dominicans will pray the liturgical hours, they’ll chant them – and he goes, ‘Just come for vespers and Mass. There’s a lot of chanting. It’s, kind of, medieval and spooky.’ And, as at Oxford, medieval and spooky is the coin of the realm, especially for American Rhodes Scholars, and so, just out of, kind of, aesthetic curiosity, I said, ‘Okay,’ and he said, ‘If you come, we can go to Balliol for dinner afterwards.’ So, we did that. I went to Mass, and the celebrant was Fr Timothy Radcliffe, former master of the Dominican order, whom Pope Francis just a few weeks ago named as a cardinal. So, he will be installed as a cardinal of the Catholic Church in just a couple of weeks from right now, as we record this. And Timothy Radcliffe is an amazing and inspiring homilist and theologian and spiritual writer, and so, both his preaching and the experience of the Mass that first time led me to want to come back. [50:00]

It wasn’t, like, all of a sudden I became a Catholic, or all of a sudden I became anything, but I just-, there was a way in which the stillness and the silence of that very simple liturgical experience allowed me to be alone with myself and, as I would later come to believe, alone with God, in a way that I realised I really needed. And so, I had a desire to come back, and so, I went back and went back again and I went on a trip with other Rhodes Scholars to Israel and Palestine a couple of months later and got to experience the holiest sites in the faith, and all of that led, eventually, to me reading the scriptures through the lens of wanting to believe – even before I believed, I just had the desire – and eventually to wanting to become a Catholic and to receive the sacraments, which I did in the spring of 2007.

CT: Wow. I love the fact that you took a chance. That one day, you just decided. You could have very easily decided not to go. And maybe you would have ended up in the same position in a different journey, but it’s really interesting to hear that it takes a small decision to actually change the trajectory of your life, really.

CH: Yes. And I think Andrew he really-, he knew. Later I would go on to be a groomsman at his wedding and friends with his wife, Emily Ludwig (West Virginia & New College 2004), who was a Rhodes Scholar in the year after us, one of the Rhodes couples out there, the double Rhodes couples who met at Oxford. I think Andrew could tell that this was something I needed. Because of the academic dynamic I described earlier, I think I felt a, kind of, emptiness. All that partying, all that need to perform a version of Cyrus that could in some paper over being blind, in some way give off a veneer of power or strength or achievement or accomplishment, was leaving me feeling really empty and hollow, and I think Andrew could tell that I was spiralling a little bit, and so, he invited me. It was an incredibly intuitive moment and instinct on his part, and it obviously completely changed my life in ways that I could not have predicted even three years later when I was baptised.

CT: Yes. It’s very powerful, very powerful to hear. So, you left Oxford and you earned a JD at Yale, and then you went on to a law firm in Washington State, but it wasn’t long until your career turned to your ultimate passion which, I would say, is public service. How did your political career trajectory unfold, and can you talk a little bit about that transition period in your life?

CH: Yes. So I started law school in 2006 at Yale and at that that time, I was pretty confused about what I wanted to do, in a way. So, my first summer in law school, I split it between working at a Seattle-based law firm and working the sales and business development office for Google, in the London office of Google, doing European and Middle Eastern sales, just an intern, actually, sitting just across a table from Anthony House (Washington & Christ Church 2003), another Rhodes Scholar from my year who had also interviewed with me. We both won from the same district. So, we spent that very stressful day waiting for our results together. We’d gotten to know each other from the Washington State interviews, actually. So, I reconnected with Anthony and he was working full-time at Google. I interned.

So, I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I worked at Goldman Sachs during my second year of law school. You know, as so many Rhodes Scholars do, I toyed with the idea of being a consultant at McKinsey and BCG. I was really confused. But during my second year of law school, my mom decided to pursue a dream of hers which was to become a judge, and so, she ran. In Washington State, the judicial positions are mostly elected. So, she ran for judge and I went back and spent my second summer working for Perkins Coie, that same Seattle-based law firm, so that I could be near her during her campaign for judge. And I also took that opportunity to help her in her campaign, kind of, an ad hoc campaign manager, giving speeches for her at endorsement meetings, and so on, and I must not have done a very good job, because she didn’t end up winning that race for judge. She, though, was later appointed to the same position by Governor Inslee. But that gave me, kind of, a window into Washington state politics. Now, I’d always been interested in politics, growing up. For me, presidential campaign seasons were, kind of, like the Olympics or the World Cup for other people: this quadrennial festival of excitement. I mean, I love politics. And then, as we talked about earlier, I got to work for Hillary and I worked for Maria Cantwell. I did a little bit of work for John Kerry’s campaign in 2004, during the Rhodes. I even, at that time, in 2008, did some legal work for the Obama campaign.

But seeing my mom run for office, kind of-, this sounds a little cocky or arrogant but seeing state legislators, meeting state legislators and thinking to myself, ‘You know what? I could do this.’ And also, Obama- I think that deep down, I wasn’t confident that an Iranian American could get elected politically. It had never really happened before. Maybe a city council position in a small town somewhere in the US. But it was totally new. But then watching Obama get elected, I thought, ‘Okay, well, if someone with that name can get elected, then surely Cyrus Habib can get elected.’ And so, I came back to Washington State, and I didn’t have it in my mind to run for office immediately, but I thought, ‘This is something I probably want to do at a certain point.’ So, I was practising law and I also became involved in a lot of different community organisations: in the Rotary Club, different boards of directors of nonprofits, and the Democratic Party. And it turned out that in 2012, there was a vacancy in the State House of Representatives, the lower chamber of the state legislature, and so, I ran for that position and won. Two years later, ran for the state Senate and won and then ran two years later to be the lieutenant governor of Washington State – which is both number two in the executive branch, though independently elected of the governor, and also president of Senate – and served for a full term in that role, during which time I also spent six months cumulatively as the acting governor of the state while Governor Inslee fan for president.

CT: That’s incredibly impressive, that trajectory. What stands out as personally significant through those different stages of your [1:00:00] time in office?

CH: Yes. Well, first of all it’s very hard to pass a piece of legislation, especially when you don’t have seniority, which-, because I moved so quickly, I never got a chance to have seniority. So my district included the headquarters of Microsoft and T-Mobile and Expedia and Nintendo America. So a lot of tech companies and so, I worked a lot as a legislator on economic development issues at first. Then I got to the chance to spearhead, to introduce legislation guaranteeing paid sick leave for nearly all Washingtonians for the first time, and that was a really meaningful piece of legislation because I knew from my own experience that whether it’s the worker themselves or their child or spouse or loved one, that illnesses can occur and that it didn’t seem fair to me that we had had the good fortune to be able to- that my father could have received chemotherapy and take time off work or that my mother could be there for him or that they could be there for me when I was a kid, but that so many workers in our state, mostly in, kind of, I guess what you would call lower-wage jobs, didn’t have that opportunity.

So, that was a really meaningful piece of legislation. When I became lieutenant governor, it was-, well, first of all, it was an 11-way primary, so, running against multiple other legislators, all of whom had more seniority than I had. It was really tough, and it meant that I had to campaign really hard in all parts of our state and get to know our state, seven and a half million people. That itself was an amazing experience, getting to know this diverse constituency – urban, suburban, rural – and then to serve as lieutenant governor. Some of the real graces there was, to be able to work on behalf of-, so again, such a diverse coalition of people and constituency, but also to be in the executive branch. And so, now, not just to be able to introduce ideas in the form of legislation and shepherd them through the process, but also to operationalise ideas, to have a staff and to be able to work with this huge state government around my priority areas. And my primary area of focus and interest was higher education, and so we ended up introducing both a number of pieces of legislation, but then also creating a number of programmes to expand access to higher education.

CT: So, could you tell me a little bit more about your decision to become a Jesuit as a more personal way to help the vulnerable, suffering and marginalised? I’m really interested to hear more about what you’re doing today and what motivates you, from looking through your political career and your, almost, confusion about what you studied and who you were, and you ultimately ended up on a very personal and dedicated journey. I’d love to know more about that.

CH: Yes. Well there are so many different ways I can talk about, why did I decide to leave politics behind, when I was elected the youngest Democrat in the country, to statewide office, at 35 years and it was, kind of, expected by everyone, myself included, that it would be on to governor or even-, I guess, at the time, my dream was to be secretary of state one day. Why leave all that behind? And the most pithy answer I can give is that I decided I’d rather be happy than successful. And for a Rhodes Scholars, that seems like an almost oxymoronic or paradoxical sentiment: what’s the difference, you know? I guess I realised that there was a huge difference. I started when my father was diagnosed with cancer again in 2013, and this time, it would take his life. He passed away in 2016. And that, of course, given my own history with cancer, got me thinking about my mortality and what’s important in my life.

Then, the election in 2016, not only the election of Trump, but even my own election and the way in which, again, as soon as I was elected, I could feel this drive in myself: ‘Okay, what’s next? Okay, I’ve got to get a book deal.’ I ended up meeting with one of the top literary agents in New York about, ‘Let’s do a book to set the stage for what’s next,’ and I just realised, like, there was- not that I didn’t have a desire to serve others – that was there – but, increasingly, it was this addiction to achieving things and to moving up, and it was never enough. Everything was a stepping stone to the next level.

And so, then, in 2018: I know it seems like cancer is through-line, but I was diagnosed-, I found a tumour in my arm in 2018, and it was the same cancer that took my father’s life, and I thought, ‘My God, is this it?’,‘Is this it? And what will my obituary say, you know? That he was the first Iranian American elected to state office, that he was a rising star?’ which I think is one of the most subversive and pernicious terms out there. The 48 hours I spent in between learning that I had cancer and learning that, thank God, it had not already spread, clarified for me-, and it was that opportunity to say, like, ‘What do I want to have done on my deathbed?’ And so, I realised that every Sunday, I would go to Mass and I would profess a faith, in a person, in a God that we are not to build up treasure on earth but that, by making ourselves small and by serving other people in humility, we are to make real God’s kingdom on earth and to unite ourselves with God for whatever comes after we die. Like, that’s what I would say with my mouth, and then, the other six days of the week, I would act as though I didn’t believe any of that.

CT: Right.

CH: And so, there was a deep inauthenticity in the way that I was living. And all of that, kind of, came into start relief as I ended up going to New York and getting radiation therapy and surgery. And thankfully, we caught the cancer early, but that’s the moment that rocked my world, and I remember praying to God: ‘God, if you give me [1:10:00] my life, I will give it back to you,’ not thinking necessarily, in religious life, but just knowing that there was something deeply inauthentic about the way that I’d been living for so many years. Again, I wasn’t a criminal, I wasn’t immoral, by public standards or anything like that, but just very focused on myself.

CT: And so, what’s life like as a Jesuit, and what are you working on right now?

CH: Yes. So, I should connect the dots and say, so, I did then-, I had read some books by a very influential public intellectual, a Jesuit priest names James Martin, and a widely read spiritual writer, and he had talked about his life as a Jesuit. And for those who don’t know, the Jesuits are a religious order within the Catholic Church, mostly, but not all, priests. We also have some brothers. But yes, it’s a religious order in the Catholic Church, known for a dedication to social justice, to interfaith dialogue, known for our colleges and universities and high schools. So, in the United States, we’re known for universities like Georgetown and Fordham and Boston College and Santa Clara. So I read these books by Jim Martin, and I had, even before all of this, questioning, but I hadn’t really allowed myself- somewhere deep down, I realised later, had been this curiosity about, what would it be like to live a simpler life, still dedicated to public service, but in way that’s much smaller and more humble, a life dedicated to study and prayer and service? And so, once all of this began to happen in my life – 2016, 2017, 2018 – I now felt that I had the courage, I experienced the courage, to take that little voice of curiosity seriously, and I began to discern, and I met with a spiritual director, and I went and visited – all in secret at that time – the novitiate, where the novices of the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits, live, on the West Coast of the US, and I applied. I also during that time had the great fortune to travel to India twice to meet with the Dalai Lama.

CT: Wow.

CH: And ironic as it may seem since he’s a Buddhist monk, but meeting him and realising, ‘I want what he has.’ As much as I admire Obama, and having met Obama, I want what the Dalai Lama has, not what President Obama has. That was also clarifying. So, I became a Jesuit. I entered in 2020, as I was right at the very end of my term as lieutenant governor, and now, I’m in my fifth year. I spent two years as a novice, living in LA, after which I took my first vows. They are perpetual vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. I then went to Chicago where I spent two years studying primarily philosophy at Loyola University, Chicago. That’s one of the places where Jesuits in formation go for their philosophy studies. And now, I’m living in Nairobi – which is why the internet connection may not be as great as we’d like for this video recording – where I’m working for the Jesuit Justice and Ecology Network of Africa, helping to coordinate our many social ministries, social and environmental justice ministries, throughout the African continent. Jesuit formation takes over a decade.

CT: Wow.

CH: And it usually takes about that long to get ordained and the formation continues even after one is ordained a priest. So, it’s a long process. I came in having done ten years of higher education, and I already have added on to that, but it’s quite something to go back to school again in your 40s.

CT: And it’s exciting: the next few years will be so exciting, filled with education and, like you said, that focus on public service is really admirable. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about the Jesuits’ focus on public service, and what that looks like, and some examples.

CH: Yes. So, one of our mottos as Jesuits is that we find God in all things and in all people. By the way, for those who don’t know, Pope Francis is a Jesuit. He’s our first Jesuit pope, and you can see this very much in his approach to the papacy. We believe that we never go anywhere to bring God to people, whether it’s travelling to a new country or to the border or to work inner-city situations. We don’t go there to bring God. God is already there. We actually go there to find God ourselves and also to help those-, both to help them in a material way, but also in a spiritual way, to help them recognise how God has been at work for them. So that’s our attitude. It’s not proselytising. It’s actually grounded in the humility that irrespective of what a person’s religion might be or what their relationship with God is, God is there, God is already there, working with and through and in that person or in that situation.

So, as a Jesuit, I’ve been able to work with the homeless of Chicago, with a L’Arche community, a community of people with intellectual disabilities whom I lived with in rural Pierce County, Washington, with people in the final days of their lives in a nursing home in LA, now here in Kenya, and high schoolers in Seattle. These are all experiences where my own appreciation of God’s tremendous goodness has been enriched and all I’ve sought to do is just accompany people. Yes, of course there are always those, kind of, tangible things that you do: teaching Much Ado About Nothing to students in an English class or bringing someone a drink of water in a nursing home: those are some, kind of, concrete, material things that you’re doing. But ultimately, what doing it as a Jesuit means is that even before I’m a priest, I’m already accompanying people in moments of significance in their lives, to help to show them the ways in which their imminent frame – to use a term coined by fellow Rhodes Scholar, the great philosopher Charles Taylor (Québec & Balliol 1952) – is being broken into by a divine spirit.

CT: That’s so beautiful. And what has it been like moving to Kenya?

CH: Well, I’ll tell you, like, it’s a learning experience. The only other country I’ve lived in is the UK, [1:20:00] which I will say, given the influence of the UK here in Kenya, actually has been helpful in some ways. One of the gifts that I’ve already received is getting to meet some Rhodes Scholars here in Nairobi. In fact, only a week after arriving here, I went to the send-off dinner for two women who have just begun their studies at Oxford. They’re Kenyan Rhodes Scholars who were about to leave. And so, at that dinner, I got to meet a number of other Rhodes Scholars from right here in Kenya. It’s been an amazing experience already. I live with Jesuits from the DRC and Zambia, Zimbabwe, Angola, Cameroon, Scotland: so, yes, it’s tremendously rewarding. I work with Kenyans right here at the headquarters of the Jesuits in Africa. And being part of a faith-based entity that works in nearly every African country has also allowed me to learn so much more about Africa. We’re talking 54 countries, so many different political, social and cultural contexts. And so this is like, for me, a second Rhodes Scholarship in a lot of ways, maybe a Rhodes Scholarship combined with a Fulbright to work here and to study and to learn here. It’s just been a tremendous experience.

CT: That’s so great to hear. Thank you so much. I’ve got a few other questions. We’ve talked about your journey and we’ve been looking forward the whole time – what was next and what did you then do? – but now, I just want to reflect back a little bit with quite a big question: what is the hardest thing you have ever done?

CH: I shouldn’t say this interview, right? That would be the right answer.

CT: That would not be great for me.

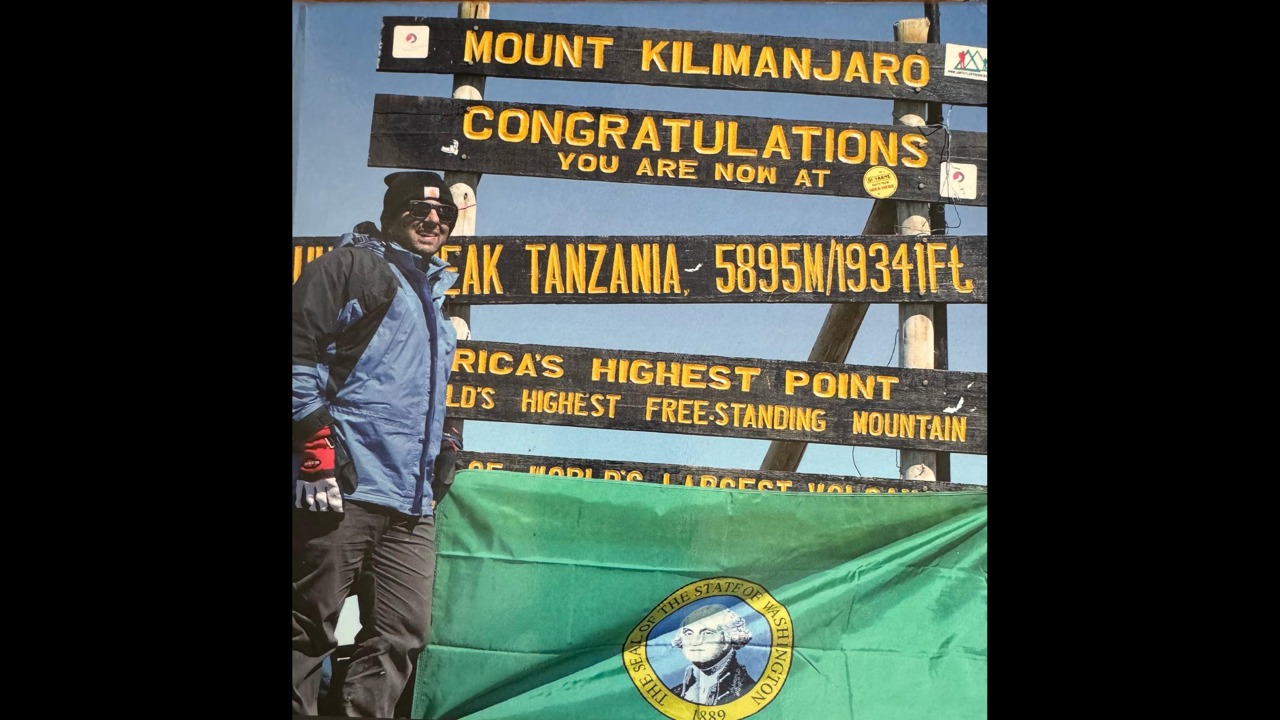

CH: No, no, no far from it. I’m actually going to give you-I feel like I risk, like, over-spiritualising, so, I’m going to give you a quite literal answer to the question, which is that, five years ago, I climbed Mount Kilimanjaro.

CT: Wow.

CH: Yes. And I did it to support a programme that my office founded when I was lieutenant governor. We started a programme-I told you the story about the playground and my mom. Well, all through my time in office, I had been thinking about, ‘What can I do to get at that, kind of, playground spirit?’, that risk-taking, and what I realised is that, in so many ways, yes, I had done a lot of things that people consider impressive: to be a blind Rhodes Scholar, to be a blind lawyer, or a blind politician, but none of those really require eyesight or eyesight is not a hugely important part of those activities or those accomplishments. I met a guy named Eric Weihenmayer, who is blind and who has summited not only Mount Everest, but fact what they call the Seven Sisters, the seven highest peaks on the respective continents. He’s an incredible athlete and writer and he’s fully blind.

And so, I was introduced to him, and so, I started thinking to myself, ‘You know what? Here’s someone who did something that’s actually quite hard, or harder if you’re blind,’ and I felt a little bit of that-, I don’t want to say competitive, because I knew I wasn’t going to try Everest. So not to compete with him, but just a little-, I felt a bit of an exhortation from his experience:‘Okay, Cyrus.’ I mean maybe it’s that, is it the third prong of Rhodes’ will, which is the one on physical ability? I felt maybe that call of, ‘Okay, do you have it?’ And being a literature person, Kilimanjaro with Hemingway and everything, had always held a place I my imagination. So, I said, ‘Look, let’s create an opportunity for other people with disabilities to have those kinds of playground experiences, to learn the outdoors and to learn, kind of, physical activity, and let’s launch it by me climbing Kilimanjaro to raise money to launch that programme.’

CT: Wow.

CH: So, we called the programme Boundless Washington. We actually partnered with a nonprofit that Eric had started, to provide some training to these young Washingtonians with disabilities and to raise money for it. I went and climbed Kilimanjaro five years ago. It was probably, in a literal sense, the hardest, kind of, discrete thing I’ve done, and the reason isn’t actually because I’m blind: the reason is because I got bronchitis on the way up. So, to reach 19,341 feet is hard for anyone, and it’s already difficult on your lungs, but to get bronchitis on the way up left me in a situation where I was, every, maybe ten steps – I was fine until the last night, when you’re summiting – I would be bent over, gasping for air.

CT: Oh, goodness.

CH: Feeling like I might have a heart attack. And I don’t know if it was grace or grit or ego or what that kept me going in the face of all that to reach the very top: certainly the friendship of the folks on the hike with me. But yes, those six days were some of the most memorable and enjoyable but, towards the end, also the most difficult.

CT: That is so impressive. What did it feel like to actually reach the summit?

CH: Pretty awful. I mean, because, the thing is, you get to, basically, almost the top, like, you’re basically at the top, but to get to the absolute highest point – the point where the sign is, okay? – you have to walk, kind of, around at that altitude for about 40, 45 minutes to get to that one spot, and I felt like I was on the moon. Like, that’s the feeling I had, like, extremely light-headed and like you’re in this barren, kind of, yes, otherworldly-, it all felt very, very otherworldly, is the best word I can use. But I was not going to be denied the photo having reached that point.

CT: That’s so impressive. Thank you for sharing that. Yes, that transported me for a second, as I was watching you climb. That’s an amazing thing to have done.

CH: Let me just say one more quick thing, though, which is that, what I learned from Eric, who taught me a bit about climbing before I did the Kilimanjaro hike, is just the tremendous creativity that exists out there in making the outdoors accessible to people with disabilities. And we did it in so many different ways. There were times when I would use my hiking poles, just like any other climber. There were times when someone would walk, several yards ahead of me wearing a bell and I would follow the sound of the bell. There were times when we would hold one of my poles laterally so that the person in front of me would hold one end and I would hold the other end and I could, kind of, feel the way that pole was moving and follow. And then, when things were really, really, kind of, tough going, [1:30:00] and we were scrambling, I would literally be holding on to the pack of the person right in front of me, moulding my bodily movements to theirs. So, it all just depended on the terrain and the circumstances, and I’ve later prayed about those experiences and viewed all of those experiences as a, kind of, metaphor for the spiritual life, or for life itself. We all go through different types of terrain and we need people in different ways. Sometimes, we even need to be carried.

CT: Yes. That’s really powerful, and that image of teamwork: like you say, it’s not always that you’re, quote unquote, holding the backpack of the person in front of you. Sometimes it’s just knowing that they’re there, and hearing that bell. That’s all you need. And it’s a lovely sentiment, actually.

CH: Beautifully put.

CT: So, my last question – and thank you so much for this. I never want to end these interviews, but this one has been particularly inspiring to me – we ask this question to everyone we interview, and it’s really interesting to see what the answers are, but do you have any words of wisdom that you would pass on to current Scholars in Residence?

CH: The first thing I would say is-, well there’s practical and then there’s maybe more aspirational. On a practical level, I would say what I think many Rhodes Scholars do say and, in fact, people told me, and I didn’t listen, which is-, and for those already there, it may even be too late, but just to say, be open to new things, whether it’s a course of study that’s very different from what you did as an undergraduate-, be open to new friendships, not just with Rhodes Scholars. My best friend-, well, I mentioned Chesa, but someone who became my godfather, actually, my sponsor and godfather when I entered the Catholic Church, Patrick Duncombe, was an undergraduate and a classicist at Oxford while I was there, and that friendship means so much to me. He changed my life. He taught me what it is be a Catholic and to care for the poor. He’s an aristocrat but he’s not what you might have in mind. He’s someone who knew every homeless person in Oxford by name and would hang out with them and share cigarettes with them, and he taught me what it means to live Catholic social teaching. So, that’s one, is just to be open to different things.

The more aspirational-, or, I don’t want to say aspirational, but the other thing I’ll say is the most important thing that’s happened to me in my life is that I’ve realised what I believe, not what I think, but what I believe. I’ve rejected the all-too-fashionable mindset, the, kind of, postmodern mindset that seeks to tell us that there is no truth, that relativizes everything. I haven’t rejected nuance, but I believe that there is truth in the world, that there is right and wrong by which-, again, I don’t want to say that in a narrow way: I mean that in the deepest sense. I found my life philosophy. I found my way of proceeding and obviously, I wouldn’t be wearing this collar if it weren’t influenced by my Catholic faith, ultimately by Ignatian and Jesuit values. When you discover that, all the other decisions around, ‘What am I going to study?’ ‘What am I going to do for work?’ all of these decisions are contextualised and they find their place, and you can live with the ups and downs of them because you have a, kind of, North Star.

And I’m not telling these hypothetical Rhodes Scholars who are listening or not listening that they need to choose what I’ve chosen, but identify what you believe by exploring these moral and social and philosophical and theological questions seriously, but with an eye towards discovery and truth, and then, once you’ve found it, commit yourself as best you can to trying to live authentically according to that way of being, recognising none of us is perfect, but at least you’ll know that you have a North Star to look to. And I think if you do that, you’re going to have a good night’s sleep more than you won’t.

CT: That’s really powerful. Thank you so much. Thank you for sharing.

CH: Thank you.

CT: I’ve come to the end of my questions, but I just wanted to leave it open, if you had anything else you wanted to add or to talk about before we finish up.

CH: No. I ‘ll just say that, as we sit here, 20 years ago, I was in Oxford, and, like I said earlier, I was at the very, very, very beginning of having my life changed by what I found there. I found God already waiting there for me. I found relationships, friendships waiting there for me. Sue Meng (New York & Lincoln 2003) and Chesa Boudin were both in my Rhodes class. Both of them have asked me to be, and I’m proud to be, godfather to their children. I mentioned Andrew Serazin and Jacob Foster and dear friends like Jared Cohen (California & St John’s 2004) and Allison Gilmore (Minnesota & Green 2004) and others. I crossed paths with Pete Buttigieg (Indiana & Pembroke 2005) and later, he would ask me to be his co-chair, his West Coast co-chair of his campaign for president.

There are so many graces and gifts waiting for us whenever we set out on a mission or an adventure, and the Rhodes Scholarship is a very rich one. So, I just want to express my gratitude for all those gifts that I’ve received, to you and to everyone at Rhodes House and throughout the Rhodes Trust and who make this opportunity available and who have worked to expand it, continue to grow it to meet the tremendous need and desire there is out there. There’s not really a need for fellowships so much as there’s a need for fellowship, and the Rhodes Trust does that. So, thank you so much. Thank you for this project, and I look forward-, because I won’t dare watch my own or read my own, but I look forward to learning about all the others that you’re interviewing. Thank you so much, and God bless.

CT: Thank you so much, Cyrus. This has been an absolute honour. I’ll just pause the recording here, but thank you so much for this interview. It’s been truly the highlight of my month. Yes, it’s been brilliant. Thank you.

CH: Thank you.

[file ends 1:39:05]