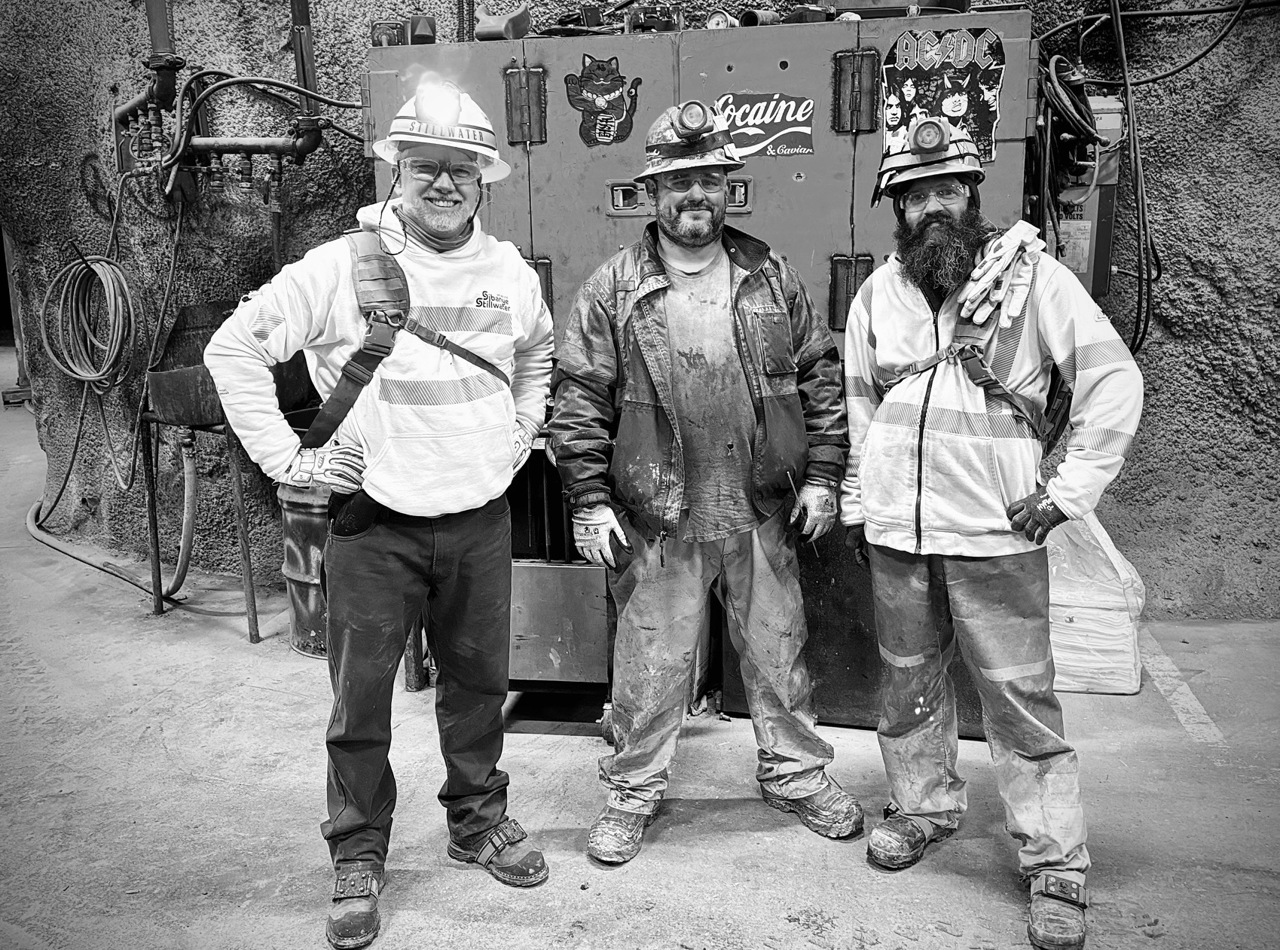

Born in Mowbray, Cape Town in 1962, Charles Carter studied social anthropology at the University of Cape Town before going on to Oxford to take his DPhil in politics. Social activism against the apartheid regime in South Africa was a major strand of his student days and his career has seen a continuing focus on improving the lives of communities through his work with mining and metals recycling across Africa and in the Americas. As Assistant General Secretary of the Rhodes Scholarships in South Africa, Carter also introduced and implemented important outreach initiatives to increase the diversity of the Scholarships. This narrative is excerpted and edited from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 15 February 2024.

Charles Carter

Diocesan College & Rondebosch & Wolfson 1986

On a socially active family life and studying social anthropology

My father had been in the RAF during World War II and trained in South Africa. My mother was a nurse at St Thomas’s hospital, and she and my father met in London when he was a young Anglican priest. After the war, he accepted a post in South Africa. Ours was a unique home in that my parents were very socially active, so we grew up without any sense of the boundaries that many of my cohort in white South Africa had at the time. There was a lot to cherish in our lives, but it was also a very weird time. Our telephone was bugged by the state security police because of my parents’ activities, and I remember vividly, when I was about nine, cycling around parts of Johannesburg stealing apartheid ‘Whites only’ or ‘Non-White’ signs on benches and posts. I used to take them down and take them home, and my parents never once asked why, in my bedroom, I probably had 50 signs that had accumulated. That gives you an insight into the bizarreness of that world at the time.

I was educated in private church schools that had grown out of a colonial experience. They had their issues and institutional baggage around culture and behaviour and norms, but they were liberal in orientation, and provided a very high-quality education for which I am very grateful. I went on to the University of Cape Town and ended up registering for a B.A. and subsequently doing an honours degree in Social Anthropology. So, my academic start was as basic and unscientific as that, but it turned out to be a very profound experience.

In South Africa in the early 1980s, social anthropology was at the cutting edge of critiquing the apartheid state and the way it had created divide-and-rule tactics around culture and language in black communities in a very dramatic way. I’ve remained very connected to the department, and I’ve endowed a fund to pay the costs of fieldwork for honours students, and that was a lovely thing to be able to give back. At university, I also worked on several student papers as a photographer and later as editor. It was a period of protest in South African universities against the apartheid state, and there were also a lot of community protests around forced removals of people in townships and in squatter camps. I did photography actively in the field around those forced removals, which was both exciting and scary as hell.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

My school in Cape Town was what exposed me to the Scholarship, and that’s obviously an application process that is fraught with critique because certainly in those days, it was a very narrow cohort that applied. And when I worked on the Scholarships in South Africa after Oxford, we all worked hard to make sure that things changed, and it’s evolved differently and slightly for the better. But at the time, I was lucky to be able to apply in the way that I did. Later, when I sat on Scholarship committees as Assistant General Secretary for Southern Africa, I have to say there is no way I would have selected me as a Scholar!

When I arrived in Oxford, I was due to do an MPhil in anthropology but when I walked into that department, the very first day, I realised this was not me. Anthropology in Oxford felt far more traditional than it had been in Cape Town. To be fair, I didn’t give it time to figure out what else was there, but I just knew this was not what was going to get me going. So, I deregistered in that first week and then scrambled to figure out what I wanted to do, and I ended up registering into politics. I hadn’t done politics as an undergraduate or a graduate student, but I found a very good Africanist cohort that was spanning different departments, so I then did the MLitt to DPhil track.

‘I had to figure it out as I went’

In my day, they dropped you in the deep end at Oxford. If you could swim, that was great. If you drowned, well then, you shouldn’t have been there, and it was as simple as that. So, I had to figure it out as I went. Luckily, there was a very strong cohort of Africanists in a seminar in South African history and politics anchored by Stanley Trapido and Gavin Williams, and with academics like Shula Marks and Terence Ranger. We also had a vibrant cohort of young Africanists, including a few Rhodes Scholars like Nici Nattrass (Natal & Magdalen 1984), Kumi Naidoo (South Africa-at-Large & Magdalen 1987), and Sarah Nuttall (Natal & Trinity 1989). The seminar included several ANC-in-exile participants, so it was very engaging.

The other thing that got me through was rowing. I’d never rowed before Oxford, but I actually made it into the university lightweight squad in my third year. There was a point where I had to choose between training through the summer with the chance to be selected for the lightweight Boat Race or going back to South Africa to do my doctoral research. I chose the latter, and I think if I have one Oxford regret, it’s not continuing with my rowing to see how far I could go.

‘No doubt the Scholarship opened doors for me’

My career unfolded in a very unplanned way, but I have no doubt the Scholarship opened doors for me. Back at the University of Cape Town, I’d done my fieldwork in Namaqualand. It’s a diamond industry environment, and Anglo American and De Beers had endowed the community that was then their labour pool with several initiatives. I went and critiqued the impact of those initiatives from a community perspective, and I wrote a very scathing dissertation about corporate philanthropy and sent it to the people I’d interviewed at Anglo American. I didn’t expect them to do anything with it other than be angry, but I got a call, effectively saying, ‘Now you’ve told us how badly we’ve done, why don’t you take up a job with us and come and see how difficult it is to get this right?’

I joined just before the first election in South Africa, and because of my Oxford doctorate in politics, I ended up managing the first democratic elections in South Africa in every Anglo American group company workplace. We took a strategic decision to create polling booths in workplaces and we got the government to align with that, and then I project-managed that across the mining, industrial, finance and other group companies of Anglo American. It was a massive opportunity, and it was super interesting.

I’ve gone on to work with businesses and often with communities and workforces that needed transition. To make it good, you’ve got to build off a values foundation that really is participative with communities and NGOs and others, and if you get it wrong, you pay a big price. My work has been about managing through the complexity of societal and economic endeavour, and how those two come together. What I would emphasise is that it’s always a collaborative endeavour. You kid yourself if you think it’s about you, because when you get it right, it’s about large groups of people who get aligned and motivated and committed and are held accountable. That’s the glue that makes it work.

On taking space and giving grace

Anybody who gets a Rhodes Scholarship is given something on a plate that is truly rare and exceptional. It’s an unbelievable gift. With that comes great privilege and pride and trepidation as to how you do justice to that gift, and I think that’s the challenge. You must figure out who you are in the process and what you bring to the equation.

To current and future Rhodes Scholars, I would say, be patient with yourself and the arc of your potential career. Those who win the Scholarship today probably graduate with enormous self-expectation, and yes, you can look to be a comet through the night sky but be careful you don’t flame out. Take space to breathe and reflect every step of the way and give yourself the grace to recalibrate. All of it ultimately has to be about being genuinely yourself, rather than trying to be true to other people’s expectations. If you can do that, I think you have a fighting chance of making a difference.