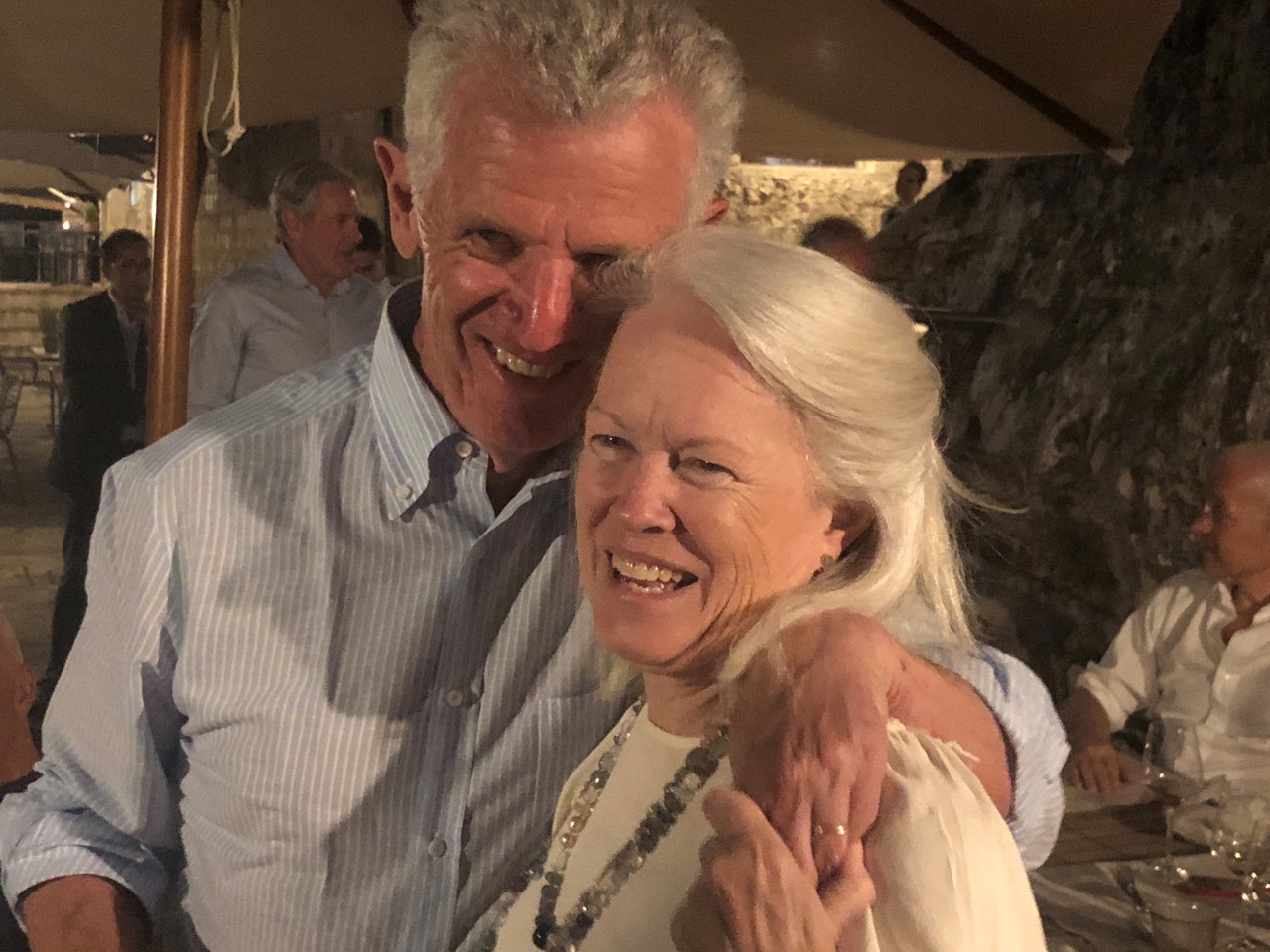

Born in 1947 in Seattle, Washington, Bruns Grayson joined the Army and served in Vietnam before going on to study at Harvard. In Oxford, he read for a second undergraduate degree in PPE (philosophy, politics and economics). After law school at the University of Virginia and working for McKinsey, Grayson moved into venture capital. He has been a Managing Partner at ABS Ventures for 30 years and sits on the boards of a range of venture capital firms. Grayson served on selection committees for the Rhodes Scholarship for 12 years, and he and his wife, Penny, are generous supporters of the Rhodes Trust and other educational causes. This narrative is excerpted and edited from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 23 July 2024.

Bruns Grayson

California & University 1974

‘A lot of things were formative about the Army’

My father was from Texas and had served on board merchant ships in the Second World War. My mother was the daughter of Serbian immigrants and didn’t speak English until she went to the first grade. My parents met in June of 1945 and got married on New Year’s Eve that year. I was one of six children, and sadly, my parents had also had twins who were born prematurely and died. The only one of my grandparents I knew was my father’s mother, Winnie, who was formidable. She was an English teacher, and when I sent her letters, she used to send them back corrected.

We ended up living in California. My parents had decided to become Catholics and we went to Catholic schools with a lot of discipline and rote learning. I didn’t work very hard, because I was good at memorising, and I was a library rat. But then, when I was a junior, I got kicked out of the Catholic high school. I went to the local public high school, and I got kicked out of that too, which was quite a trick. My father and I had butted heads a lot, and just before my 18th birthday, he told me I could leave home. I spent the summer doing odd jobs and living pillar to post and then, in September, I enlisted in the Army. I think my state of mind was that I needed to go away. Let’s just say I realised that if I carried on hanging around with my friends, there were poor trend lines.

The Army gave us a zillion tests and based on those, I was eligible to go to officer candidate school. In those days, the Army was the only branch of the service that would let you go to OCS without a college degree. A lot of things were formative about the Army. When I first enlisted, I was in barracks, living cheek by jowl with people from every conceivable circumstance, background and education. Because of the war in Vietnam, promotion happened relatively fast, so that by the time I was in Vietnam, I was a first lieutenant, and then, while I was out there, I became a captain. I was an ordnance officer, which meant that when I got shot at, it was random rocket attacks, occasional roadside bombs, stuff like that. I ended up as a company commander, responsible for around 200 men. It’s funny: I never lost sleep about that job. If I had it now, I would probably freak out.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

On the base, I enrolled in University of Maryland extension classes, and one of the guys teaching was named Jack Wheeler. He said to me, ‘What are you going to do when you get out?’ and I said, ‘Well, finally, I’m going to go to college.’ I’d taken the SATs in Vietnam and got good scores, and Jack said, ‘You should apply to Harvard.’ I knew nothing about admissions, but he did. For whatever reasons, the application materials didn’t arrive, so Jack helped me put together all the stuff that would have been required and then told me to write to the president of Harvard. He wrote back in the kindest possible terms saying that he was going to make sure the materials would get to me, and would I be kind enough to fill out a regular application? I did, and I got in. It’s so hard to imagine how my life would have been if I hadn’t met Jack Wheeler. He kept in touch with me while I was at Harvard, and he was the one who encouraged me to apply for the Rhodes Scholarship.

I absolutely loved Harvard. I majored in History and Literature, I did a bit of rowing, and I was also a sportswriter on the Crimson. I had no plans for what life would look like after college, but I did want to travel and see another country. That was a major reason for applying for the Rhodes. I spoke to the secretary of the selection committee for California, Sandy Tatum (California & Balliol 1947), who was one of the world’s most generous spirits. He was very encouraging, and I enjoyed the questions and discussions in the interviews. At the interview, I also made the first of an amazing group of friends from my Rhodes class in Tom Barron (Colorado & Balliol 1974).

On adapting and flourishing in Oxford

I remember arriving in Oxford after an overnight flight feeling like a zombie, but I soon settled in. In my degree, I was focusing on politics and philosophy, and my college, Univ, was a real big-hitter in philosophy especially. The intellectual framework of the Oxford tutorial struck me at first, and incorrectly, as easy. Then I did it for a while and I discovered that the tutors were very good at calibrating your intellectual capacities. It only took one instance of me not showing up well prepared to find out just how long an hour is. It was distinctly awkward, and I thought, ‘I’m not going to do that again.’

I rowed for the college, and that was a great way to meet people outside the group of Rhodes Scholars, because the Brits could be pretty remote, certainly at first. In my first year, I had the room that Bill Clinton (Arkansas & University 1968) stayed in a decade earlier. And then, in my second year, I lived in the Master’s lodgings. The deal was that the Master’s wife would let you live there as long as you helped out occasionally at lunch parties, being the extra man or carrying trays. The Master and his wife were really good people. They would memorise the names and faces of every single undergraduate and know all about them right from the get-go. The dons and the administrators also took their relationships with people so seriously. It was impressive.

‘They hustle, they have imagination and energy’

I was at Rhodes House after I’d finished my degree when I met Jerry Hillman (Massachusetts & Balliol 1966), who was a junior partner at McKinsey. He encouraged me to talk to McKinsey in New York, but my girlfriend Penny, who would later become my wife, had just started working in Washington, DC and I wanted to be near her. So, I asked for a job in the DC office, and I got one. I worked for McKinsey on and off while I was in law school. I realised soon I wasn’t going to be a lawyer, and McKinsey, for me, served as my business school, my introduction to commercial life.

It was 1980 and venture capital was a new thing. I landed at a firm called Adler & Co. After a few years, a friend of mine from law school recommended me to some people at Alex. Brown & Sons, who had raised a venture capital fund but didn’t have anybody dedicated to it. I ended up running their venture funds and after a while, my group spun off. That’s how ABS Ventures started. I was not possessed of the inclination or ambition to manage very large amounts of money, but I’ve always liked and admired the people I was working with, because they hustle, they have imagination and energy. They’re fun to be around, and that’s why I still do it.

‘It’s like a jewel’

I’m not sure today’s Scholars need any advice: they’re on top of their game. But I used to say to Scholars elected when I was running a selection committee that they should savour the experience in Oxford. It’s a different thing from your other educational experiences, and for that time, you’re not on the treadmill in the same way. It’s like a jewel that’s separate, that has its own identity.

What inspires me now? My family, certainly. My Rhodes, Oxford, and Harvard classmates too: those friendships where you can just walk into a room and pick up the conversation where it left off, no matter how long it’s been. What the Rhodes Trust does for people is important, and different, and that’s why Penny and I support it. I think if people take the time and the interest to encourage you, like Jack Wheeler encouraged me, then the idea of giving back just starts to come about by osmosis. It seeps into you, and you think, ‘I’ve got to try and help too, if I have an opportunity.’ It’s the least you can do.