Born in 1938 in Lawrenceville, Georgia, Bob Edge studied at the University of Georgia before going on to Oxford to read for a second undergraduate degree in PPE (philosophy, politics and economics). After Yale Law School, he took up a position with Alston, Miller & Gaines (now Alston & Bird) in Atlanta and remained there for 58 years, focusing on estates and trusts work. Throughout his time as a practising lawyer, and now in retirement, Edge has been a vigorous supporter of the arts and of education, sitting on the board of the Metropolitan Opera and helping to set up the Foundation Fellows programme at the University of Georgia. His support has also been vital to the Rhodes Trust. A member of many Scholarship selection committees over the years, Edge was also the president of the American Association of Rhodes Scholars (AARS), where he pioneered the Bon Voyage weekend for newly elected Scholars from the US and Canada. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 18 September 2024.

Bob Edge

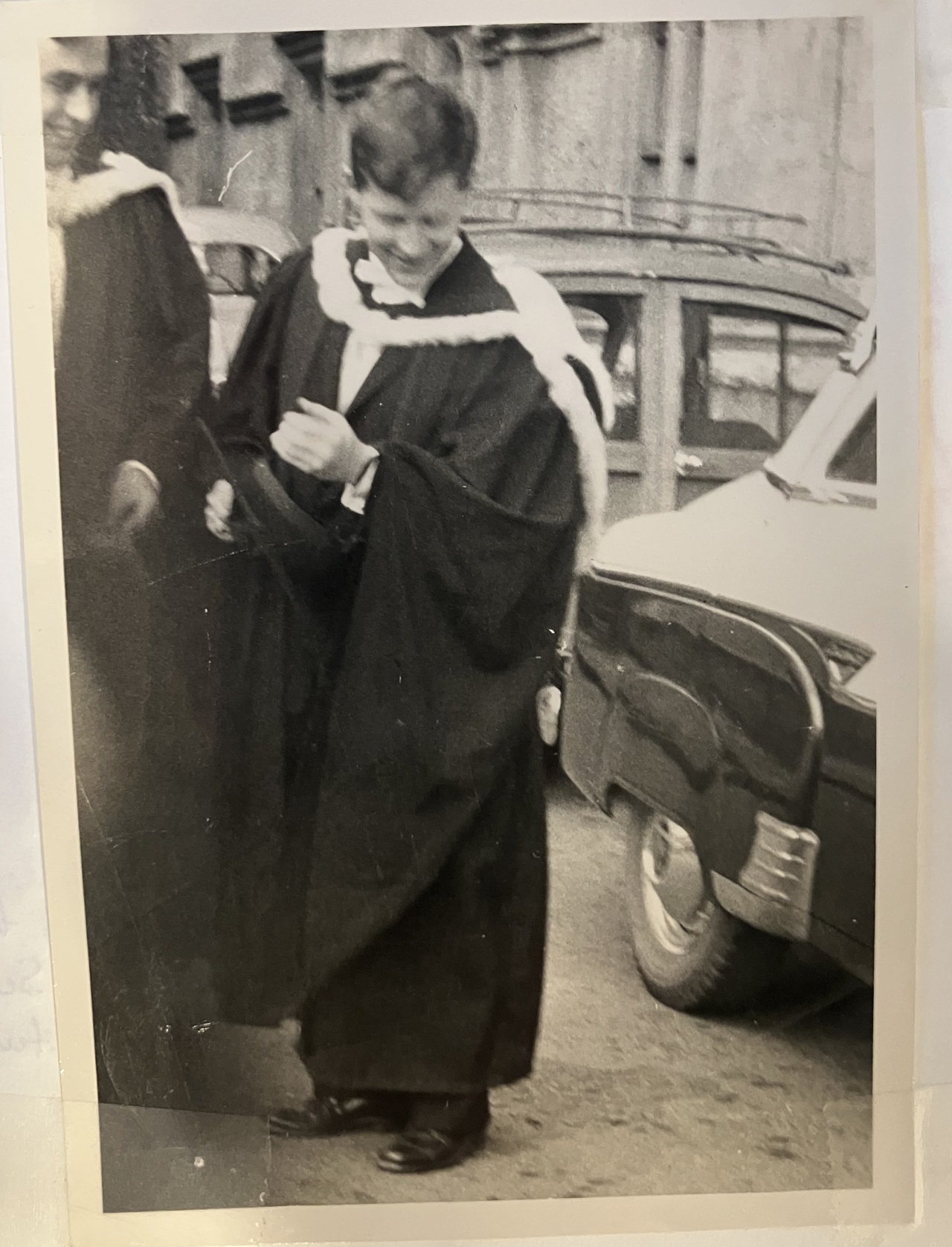

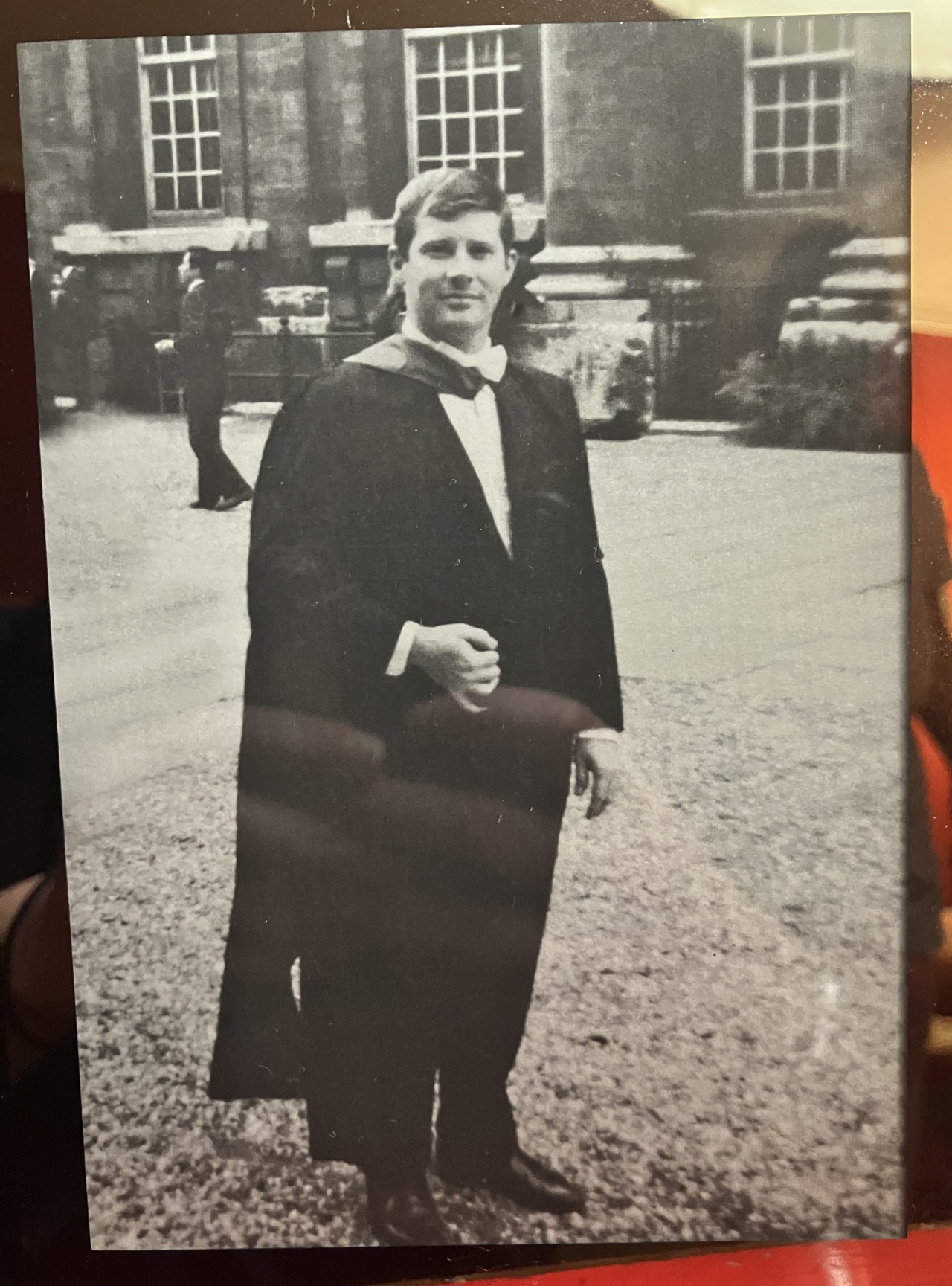

Georgia & Oriel 1960

‘A very typical Southern town’

I grew up in Lawrenceville, which was a very typical Southern town. I felt privileged to grow up in a small town, because that dynamic is so important, with everybody in the same rowboat, except, of course, that at that time, it was all segregated. I was a tiny boy, redheaded, and people say to me, ‘Well, were you bullied?’ but I never was, because the other people in my town would not have stood for that. So, I loved growing up there.

I had a great education when it came to English literature and that sort of thing, although in my little country high school, we had almost no science. But the memorable element of my education was that I was interested in music, and so, when I was in seventh grade, I was taken on by the head of the music department at the University of Georgia in Athens. I started going over there for piano lessons with Hugh Hodgson, who was what you might call the musical czar of Georgia at that time. It was a life-changing experience for me. When I started going to the Brevard Music Center, I even thought for a time I might have some kind of career in music, but I had the sense to know that I wasn’t good enough to be a professional pianist and I expanded out.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

At the University of Georgia, I was involved in all kinds of activities and I kept winning all kinds of awards, but I didn’t know anything about the Rhodes Scholarship, except that Morris Abrams (Georgie & Pembroke 1939) had won one. He came to speak to the Phi Kappa Literary Society when I was president, and he spoke to me afterwards and said I should apply. I thought, ‘Well, I might as well try.’ When I won it, I was thrilled, although even then, I didn’t know exactly what it meant.

When I was elected, I was the first Rhodes Scholar to come from Georgia for about 14 years. There was a lot of excitement about that, and I was actually invited to speak to the Georgia legislature. What does a 22-year-old say to the Georgia legislature? Well, that was when we were going through the integration crisis, and the legislature was debating whether to keep the public schools open or to close them, rather than integrating them. I was later told that I was the first person to openly say on the House floor, ‘Gentlemen, we have got to keep the public schools open.’ It seems crazy that they would even think of closing them rather than integrating them, but I take pride in having said that.

‘I decided to take advantage of the cultural opportunities’

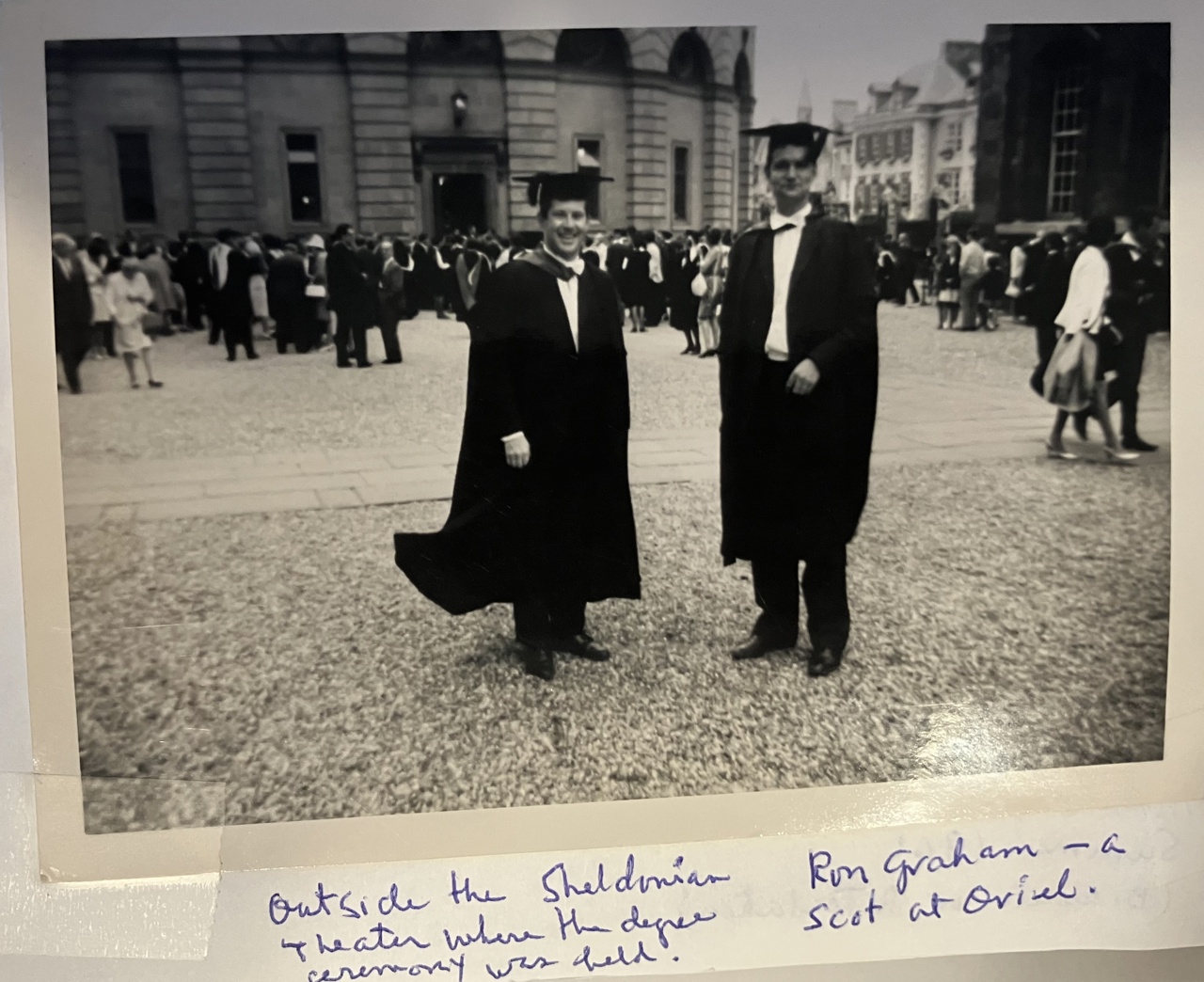

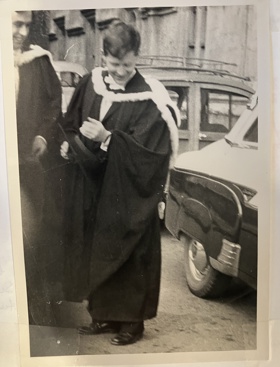

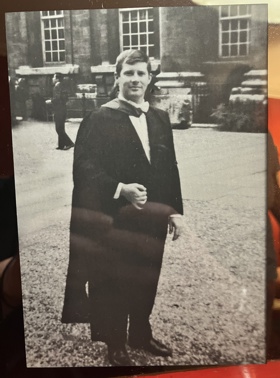

My class of Scholars from the US sailed over to Southampton together, and it was a wonderful way to get to know one another. I remember the bus arriving in Oxford late in the evening, and the driver saying, ‘All out for Oriel.’ So, I got out, and it was pitch black, with no lights. I managed to find my way to the door, but the porter wasn’t very friendly, and I was thinking, ‘Where in the world am I?’ Just then, Ron Lee (Minnesota & Oriel 1959) came out and said, ‘You must be Bob Edge. I’ve been waiting for you, because I know how traumatic it was last year when I arrived here and I was left on my own.’ He took me to my staircase, and introduced me to a few people, and I was off and running.

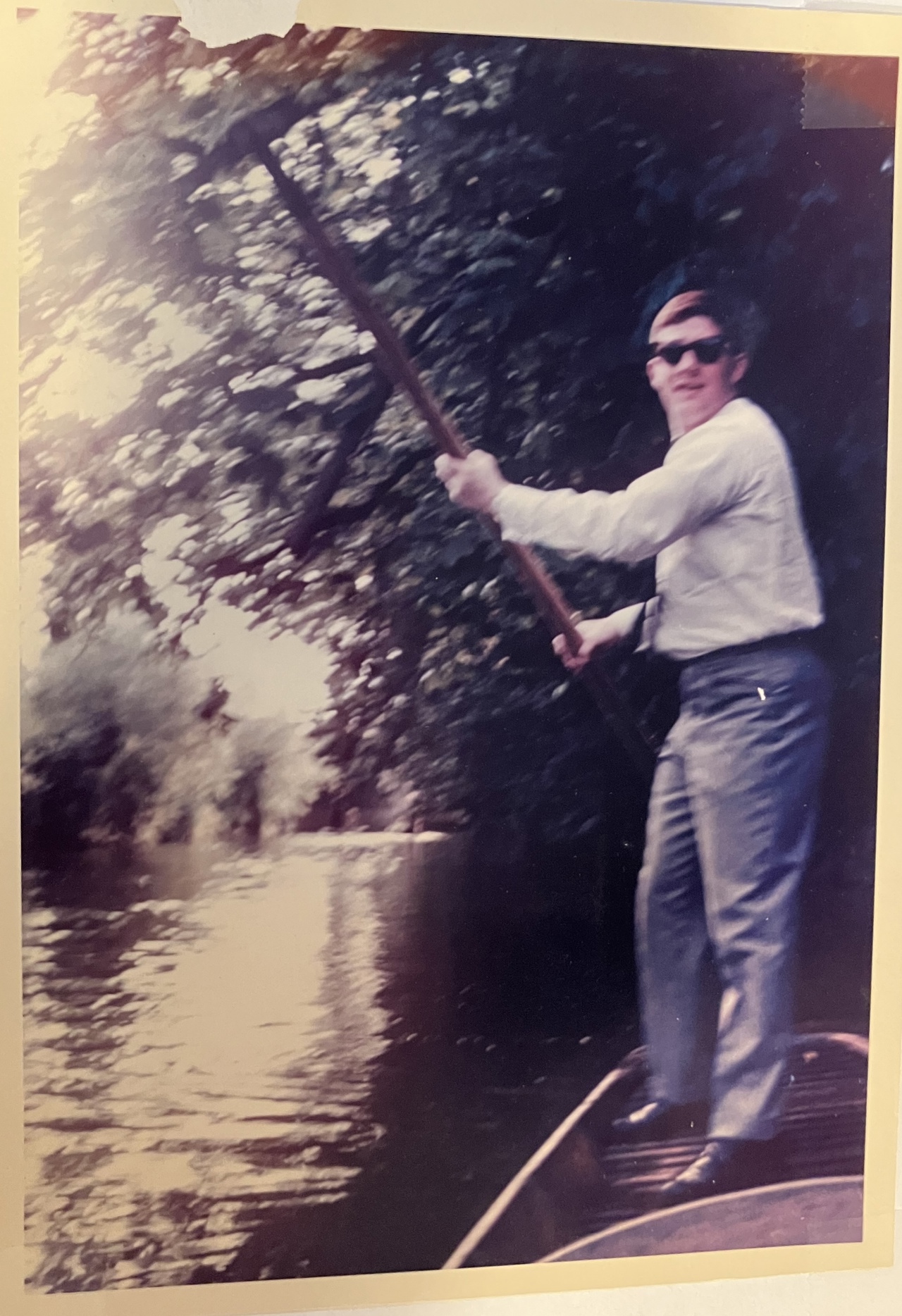

I started off intending to read English, but I wasn’t really enjoying the books that had been recommended beforehand, and then I met a lawyer in Atlanta who had been at Oxford, and he suggested I should think about law. When I got to Oxford, I still wanted to be a lawyer, but I did not have a good start with the law course, and so, I switched to PPE. I have to say, my tutors were not great. So, instead of working to get a first, I decided to take advantage of the cultural opportunities there. While I was at Oxford, I went to over 100 operas and over 150 plays, and had the most incredible trips in the UK and in Europe. I know exactly what I did, because every day, I would write a letter or postcard home to my parents, and my mother kept all of them, around 710 or so. It’s been wonderful to recall those rich details of my life at that time.

‘It was just right for me’

I went on to Yale Law School, and when I graduated, I was asked if I wanted to consider a clerkship. But by then, I was 27 and I wanted to get back to Atlanta and start working. I joined Alston, Miller & Gaines and I worked doing whatever was expected. I had actually been offered a job with a firm I worked with in New York, and because of the musical resources there, I was tempted to take it, but I came back to Atlanta, and I’m so glad I did. I ended up specialising in estates and trusts law, and it was just right for me. It was so highly personalised. I would sometimes find myself working with several generations of the same family. My clients would become my friends, and my friends would become my clients.

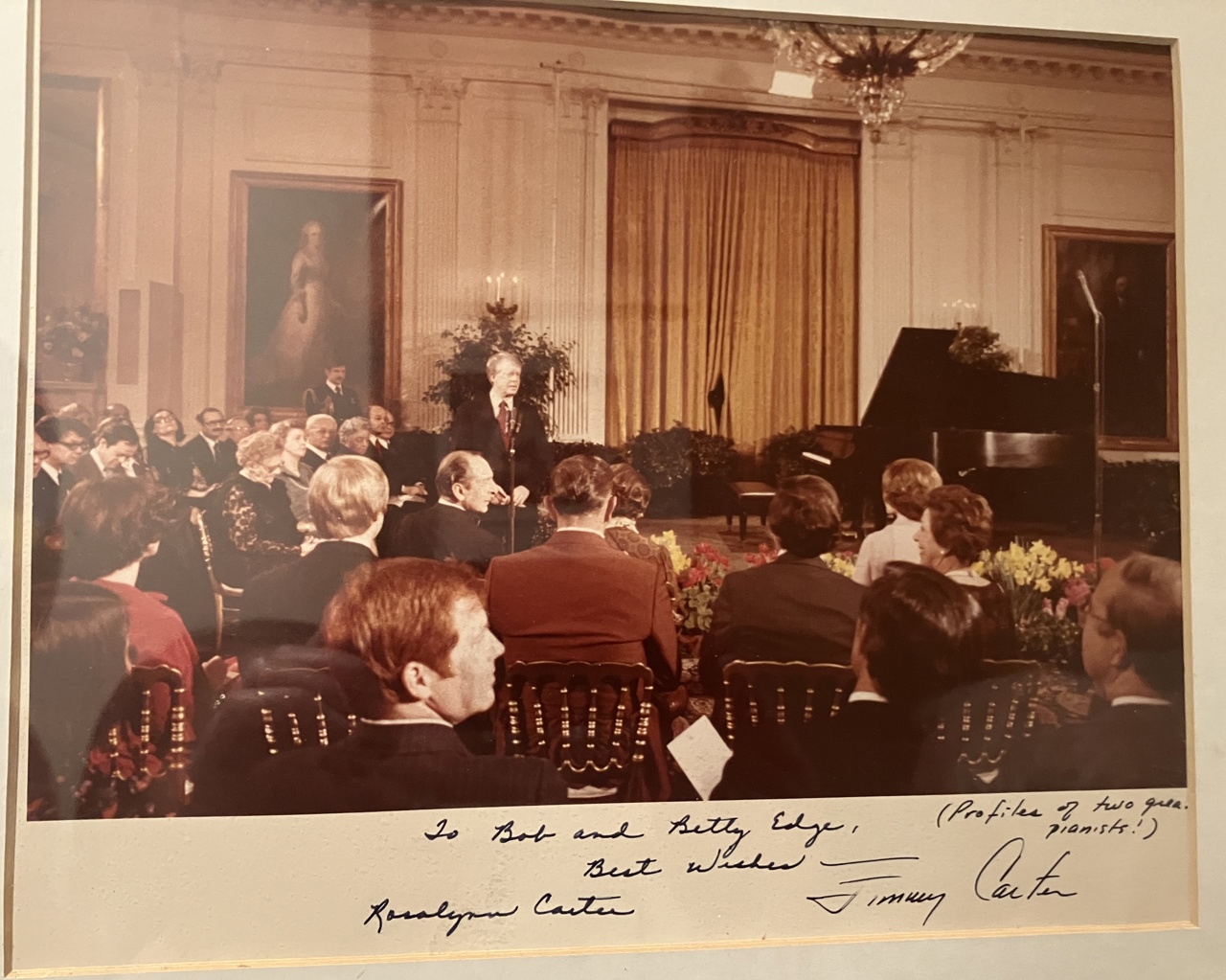

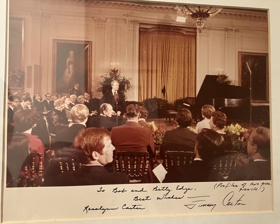

There was also a lot of crossover with my love of opera, not least because a lot of the clients I worked with were also opera-goers. My passion for opera has been so important throughout my life. I became the head of the group that sponsored the Metropolitan Opera tour to Atlanta, and because of that, I was then asked to join the advisory board of the Met. Later, I was asked to join the managing board. I taught and still teach classes, trying to take people who know little about opera and music in general and say, ‘Let me tell you why this is wonderful.’ Music has provided so many special opportunities. Jimmy Carter, who had been a client of mine, became a friend, and my wife Betty and I would invite him and his wife to the opera. Later, when he was President, I even managed to get him to come to the Met, and we’ve maintained our friendship to this day.

Alongside law and music, I feel so lucky to have had the opportunity to work with the American Association of Rhodes Scholars. As president, I introduced the Bon Voyage weekend, to give newly elected Scholars a chance to get to know each other and former Scholars across a few days, now that Scholars don’t sail over together. I think I’ve also been on 31 selection committees, which may not be a record, but surely comes close. And, of course, giving back to the University of Georgia is also something that is very easy, because it’s done so much for me. When I think about the things I’m proud of doing, one that comes very near the top is starting up, with others, the Foundation Fellows programme at the University of Georgia. This year, the University of Georgia had three Marshall Scholars, and one of those three didn’t take the Marshall, but only because she took the Rhodes instead!

‘The Rhodes Scholarship was unbelievably impactful’

To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say, don’t listen to people who were at Oxford more than five years ago! All the dynamics have changed so much. Certainly, for me, the Rhodes Scholarship was unbelievably impactful, although I should say, being a Rhodes Scholar and having served on selection committees, there is so much luck involved in getting the Scholarship. I think virtually anybody who makes it to the final stages would do just as well as any of us did. So, my central feeling about the Scholarship – about my life, in fact – is gratitude for what I’ve been given.

Transcript

Interviewee: Bob Edge (Georgia & Oriel) [hereafter ‘BE’]

Moderator: Jamie Byron Geller [hereafter ‘JBG’]

Date of interview: 18 September 2024

[file 1 begins]

JBG: This is Jamie Byron Geller on behalf of the Rhodes Trust, and I am here on Zoom with Bob Edge (Georgia & Oriel 1960). And we are here today to record Bob’s oral history, which will help us to launch the first ever comprehensive Rhodes Scholar oral history project. So, thank you so much, Bob, for joining us in this initiative. Today’s date is 18 September 2024. And before we begin, Bob, would you mind saying your full name for the recording, please?

BE: Robert Glenn Edge.

JBG: Thank you. And do I have your permission to record audio and video of today’s conversation?

BE: Absolutely.

JBG: Wonderful. Thank you so much. So, Bob, we’re having this conversation on Zoom, but where are you joining from today?

BE: I’m at my house, in my wife’s media room.

JBG: And where is home?

BE: Home is Atlanta, Georgia, in Buckhead.

JBG: And I know we’ll talk about this in a little bit more detail, but how long has Atlanta been home?

BE: Well, you know, I grew up in Lawrenceville, which is 25 miles away. But we were always coming to Atlanta for all sorts of things: doctors, clothes, that sort of thing. And then, after I got out of law school in 1965, I came to Atlanta. Been here ever since.

JBG: Right. And were you born in Lawrenceville?

BE: I was born in Lawrenceville, absolutely.

JBG: Wonderful. And when were you born?

BE: I was born on 23 June 1938. So, now I’m talking to you, I’m 86.

JBG: Wonderful. And I know we spoke about this a little bit before we started recording, but I would love to know more about your childhood in Lawrenceville. Would you mind sharing with me what you shared before we started recording you?

BE: I’d be glad to. Lawrenceville, when I was living there, was a town of 3000 people and a typical Southern town and I felt privileged to get to grow up in a little town because the dynamic there that is so important is that in a small town, everybody is in the same rowboat. So, you can play with the boy from a family with a little more money or you can play with the poorest people. It was segregated all the time I was there and it was a typical, you know, Southern town. Loved it, and the neighbours all took care of each other and no question about it. And I was a tiny boy, was redheaded and, you know, all of that stuff, and people say, ‘Well, were you ever bullied?’ I was never bullied because no, the town would not have stood for any of that sort of thing. So, I didn’t have any of that experience, and so, I loved growing up in Lawrenceville.

JBG: That’s really lovely. And I’m curious about your educational experiences, your elementary and high school education experiences in Lawrenceville.

BE: Well, the thing is, we had no science really in this little country high school. We had no science to speak of. But I got a great education when it came to, you know, English literature, for example, that sort of thing, and all that, and when I got to Georgia, I was well prepared, except for scientific things.

JBG: And are there particular teachers from your earliest education years that stand out as particularly memorable.

BE: Well, what I would say is, the memorable part was that I was interested in music. And so, I was lucky to be taken for piano lessons by the head of the music department in Athens at the University of Georgia when I was in seventh grade. So, I started going over there. My wonderful mother would drive me to Athens – it was about an hour away – and I’d have lessons with Hugh Hodgson, who was, kind of, the musical czar of Georgia at that time, and he was wonderful, and he was the biggest influence in my life after my mother. So, you know, I had my regular education but I had this extra component that was unbelievable, because Mr Hugh would say to my mom, ‘This boy needs to come over and hear this lecture,’ and, ‘This boy needs to come to his recital.’ And so, that was the extra element in my high school education that I was so privileged to have. It was a life-changing experience for me.

JBG: Really lovely. And did you have a vision, as you were growing up, of what you thought your career could look like someday?

BE: Well, you know, I did very well in school, but I had this special musical element in my background. I played with the Atlanta Symphony when I was 15 or 16. And, you know, was captain of the literary team and we won the state championship. I’ve won a fair number of things, but I think that nothing was more thrilling than when my little country high school won the state literary meet, and I can just remember that with such joy. It was just great. And then also, in high school, I started going to Brevard Music Center – that was Transylvania Music Camp at the time – and that was my first exposure to people, you know, that were like me really, with this special musical interest, and I went there for four summers and it was just such an expanding experience and I just loved it. And so, it was the music aspects that made me education and my life in Lawrenceville different.

JBG: Yes. And I apologise if you mentioned this, Bob, but what instruments were you gravitating towards at this time?

BE: Piano.

JBG: Okay.

BE: Yes.

JBG: Wonderful.

BE: And so, I guess, in the back of my mind, you know, I had this music factor in my life, but, you know, when you’re 15 or 16, you really don’t-, I didn’t know-, I excelled in that area and all of that, and I guess I thought about having some kind of career in music. I’m not sure, if you really want to know the truth, but when I went to Brevard for the music camp, I excelled there. But thank goodness, I had the sense to know I wasn’t good enough to have a really good life as a, you know, pianist, and so, I expanded out, thank goodness.

JBG: And so, you mentioned when you were taking lessons with Hugh Hodgson, that was at the University of Georgia?

BE: That was at the University of Georgia. So, I got to started working and going to the university and taking classes and attending lectures and meeting people when I was in the seventh grade. And so, I stayed with Mr Hugh, you know, for ten years, because I went to the University of Georgia and started out as a music major, getting a BFA. But fortunately, and I don’t know how this happened, I thought, ‘No, I need to be broader than that. I need to get a BA, not a BFA.’ And so, then I decided-, you know, to be a successful musician, I felt you had to be in, kind of, the top one tenth of one percent of musicians. But, you know, there are other things that you don’t have be at the very, very top to live a pretty good life. So, I decided I would be an English professor. Anyhow, so, when I went through the Rhodes competition, I went through, you know, on the idea of becoming an English professor in college. And so, that was another big development.

JBG: Yes.

BE: And then, just to go on through, at Georgia, I was, you know, involved in all kinds of activities and kept winning all kinds of awards, and I was studying or working all the time, and that was so good for me. That’s exactly what I needed to do. And so, I debated, I was captain of the debate team and head of this and head of that, but I was working all the time and thank goodness, because it was good for me. [10:00]

JBG: And you mentioned speaking about your hopes to be an English professor as part of your Rhodes interview and application process, but I’m wondering if you would mind if we back up for a moment. I would love to know about what inspired you to apply for the Scholarship.

BE: Well, I didn’t know anything about the Scholarship except, you know, there was a wonderful former Rhodes Scholar from the University of Georgia, Morris Abram (Georgia & Pembroke 1939), and he had been very distinguished, and he said, ‘You know, you ought to apply for the Rhodes Scholarship,’ because I was president of the literary society, Phi Kappa, on campus, and he came over to speak, and he had followed me because I had been involved in musical activities in Atlanta. So, he knew about me, and he said, ‘You know, Bob, with your interest in all sorts of things, you ought to apply for the Rhodes.’ Well, I didn’t know anything about the Rhodes, and Mr Hodgson said, ‘Well, it’s fine to apply, but you know, just know in advance you’re not going to get it.’ So, anyhow, that’s how it came about. You know, I was winning all the other awards, so I thought, ‘Well, I might as well try for this one,’ and I did.

JBG: And had you had the opportunity to spend time in the UK prior to that?

BE: No, I had never been abroad?

JBG: Okay.

BE: I graduated from high school in 1956 and graduated from Georgia in 1960 and, you know, I’d ridden the plane for three or four times. But I mean, that was a different era. People just didn’t do that at that particular time and, you know, we were still coming-, America was doing well. We were still, kind of, post-war in some ways and just beginning to take off into this modern world we now know a little bit more about.

JBG: And do you recall that moment of learning that you were selected for the Scholarship?

BE: I do, yes. You know, I remember well. We were at the Capital City Club downtown, where the interviews had been held, and I was thrilled. I didn’t know exactly what it meant, quite frankly. I knew that Oxford was outside of London, and that was the extent. So, today, to hear these, you know, people who have been elected and they’ve been in correspondence with their tutors for years and have spent time in Oxford and Uganda, and it’s unbelievable how different the profiles are these days, I think. But anyhow, that’s what I can tell you.

JBG: And did you sail to Oxford with your class?

BE: I did. In those days, we gathered, and Courtney Smith (Iowa & Merton 1938), he was the American Secretary, and he had a luncheon and then we all sailed together on the SS United States. They gave us first-class state rooms and then we ate in the tourist room, or whatever, but it was all wonderful. So, we had four or five nights together, you know. At that time, it was the SS United States, which is about to be scuttled. It was the fastest liner on the ocean and it was incredible. We had a wonderful time, and that was so important, to get to know the members of my class at that time.

JBG: That’s wonderful. And do you recall the moment of arriving in Oxford for the first time?

BE: I do recall. We landed at Southampton and then the Warden met us for dinner someplace and then we got on the bus to go to Oxford, and when we got to Oxford, I remember it very well. We got to Oriel Square and the bus driver said, ‘All out for Oriel.’ So, I got out in the pitch-black dark. There were no lights.

JBG: Wow.

BE: Except for lights coming from a doorway, and I assumed that might be Oriel, and I went, and it was the doorway to the porters’ lodge, and the porter wasn’t very helpful. He told me where my room was and that was about it, and I think, ‘Where in the world am I?’ And then, there was this guy, his name was Ron Lee (Minnesota & Oriel 1959), a big, tall, good-looking blond-headed guy from Minnesota, and he was captain of boats, and he came and said, ‘You must be Bob Edge, and I said, ‘I am,’ and he said, ‘Well, I’ve been waiting for you, because I know how traumatic it was last year when I arrived here and I was left on my own.’ And so, he took me to my staircase, introduced me to a couple of people, and I was off and running.

JBG: Oh, that’s really lovely. So, Ron was a Rhodes Scholar from the class of 1959?

BE: Yes, that’s right.

JBG: Okay. And were you the only Scholar in your class who was at Oriel that year?

BE: Yes, I was the only American Rhodes Scholar, yes.

JBG: Okay. And what did you read at Oxford?

BE: Well, I have an interesting history. I was going to read English, but my tutor had sent me a letter at the beginning of the summer, before I was to go up, and he said, ‘Dear Edge,’ and I didn’t know that was a mark of acceptance. So, ‘Dear Edge, I hope you will pay attention to the following works before you come,’ and then he gave me this unbelievable reading list, you know, also Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Reader and all this stuff. I started reading-, I graduated from Georgia. I’d had a very difficult, challenging, work-hard year, and took two weeks off and then starting reading, eight hours a day.

JBG: Wow.

BE: And so, anyhow, I was in the middle of that project-, because my personality is, somebody in authority says, ‘Do this,’ and then I’m likely to do everything I can to get it done. So, I was really working, and in the middle of that summer, I met a lawyer in Atlanta who had read law at Oxford, and a friend of my mother knew this guy, used him as a lawyer: his name was Allen Post (Georgia & Pembroke 1927). He invited me to lunch. And so, anyhow, I went down, and he asked me what I’d been doing, and I told him what I’d been doing, and at that time, I was in the middle of The Faerie Queene, and he said, ‘You think you want to do that the rest of your life?’ and I said, ‘Well, I’m not so sure,’ and he said, ‘Well, you ought to consider being a lawyer. You’ve done so many things that mark lawyers, like debating and all of those things.’ And so, I think, on the spot, I became committed to becoming a lawyer: ‘Sounds great.’

JBG: Wow.

BE: Well, so many big decisions in life are made spur of the moment, I’ve found. So, anyhow, at that point, I decided to change. So, when I got to Oxford, I got permission to change from English to law. You couldn’t do this now, I understand, but I got permission to do that, and then, I take it as divine signals about reading law there, because one of my first assignments was out of college, to this tutor who turned out to be a grumpy old fella, and I thought, ‘I’m not sure I want to spend a quarter with this guy,’ and also, the class smart alec was assigned to be with me. I thought, ‘This is not a good sign.’ And then, the other course was the Roman law of sale, and you had to do a lot of Latin. I had no Latin. So, I thought, ‘You know, maybe this is not a good idea.’ So, then I got permission to change to philosophy, politics and economics, because Morris Abrams, who is the fellow who had first told me about the Rhodes Scholarship, he said, ‘If you get to Oxford and you’re not sure what to do, read philosophy, politics and economics. It’s just broad enough.’ And I’d been a music and English major in college, and so, I’d never had an economics course. I’d never had a philosophy course. So, it was a chance, really, to broaden, for somebody who was maybe on the path to going to law school. So, that’s my history there.

JBG: Lovely. And did you live in college both years that you were in Oxford?

BE: I lived in college both years. The first time, I had nice rooms, but on the second floor, and I had an [20:00] upright piano in my room that I rented from the High Street. And then, my second year, I had the pick of the rooms of the college. It was between the first and second quads, with a huge sitting room, and I had a grand piano there.

JBG: Wow.

BE: Yes. And then, there was my bedroom. My bedroom was an oversized closet, basically, with no heat. I thought I would probably die in the night from being cold or something, but my mama sent me an electric blanket, a US electric blanket, because in those days, the tabloid newspapers were filled with stories every morning about how many people had died in the night from the non-American electric blankets, you know, catching on fire or whatever else. But my mama sent me an American one that I, you know, got the converter to work on, and I warmed up at bedtime. So, that was good.

JBG: And were there activities out of your studies that filled up part of your time at Oxford?

BE: Well, my main activity, if you really want the truth-, well, first, I have to back up. It turned out that my tutors at Oriel for philosophy, politics and economics, they were very subpar. The worst teaching I ever had was at Oxford, but that’s not bad. I’m going to tell you why. I mean, and there were special reasons: the economics don had been very distinguished in 1930, but that was it with them, quite frankly, and he wasn’t there. The philosophy don, who was supposed to be pretty good, he was in America. So, they brought in somebody who had never taught, and he was no good. And then, I had a very lazy politics don. But that turned out to be a good thing. So, instead of working to get a first, I decided, ‘No, I’m going to take advantage of the cultural opportunities I have.’

So, while I was at Oxford, I went to over 100 operas. I went to over 150 plays. I went to every lecture, you know, by a distinguished person. It was not so much I was interested in this subject as just seeing this distinguished person, you know, which was great. And then, just travelling. So, anyhow, in those days, Rhodes Scholars didn’t go home at Christmas, so, I was travelling, and it was unbelievable, because Oxford, then and now, eight weeks a term, really, those three terms, and then the rest of the time, you know, you had on your own. You were supposed to be reading, but that was not a big deal in those days. You know, I really don’t know what goes on today, but I was used to working all the time at Georgia, and the workday at Oxford, you know, they thought I was overworking by reading four hours a day. But it turned out to be so liberating, because instead of doing things that I could do and I knew I could do, I was free to do things I hadn’t done, with all of that opera, all of those concerts, all of those plays, and it was just unbelievably fabulous for me.

JBG: That’s amazing. It sounds like you did quite a bit of travelling. Was that within the UK, primarily, within Europe?

BE: No, it was western Europe.

JBG: Western Europe. Okay. And at that time in the UK, Rhodes Scholars, and maybe some others, would get a letter from a wonderful lady called Miss MacDonald of Sleat, and she was the head of something called the Dominican Society, and these were ladies who were supposed to be helpful, offer opportunities to American students, like Rhodes Scholars, who were there. And Miss MacDonald would say, ‘Can we arrange for you to visit in a home during the Christmas vacation?’ or whatever else. So, the first night I spent in London was in Thackeray’s house. That was owned by a lady Member of Parliament. And then I went on several of those. You know, unbelievable experiences, and I wouldn’t take anything for that. And they mainly just provided, you know, room and board and then we were free to, kind of, wander around as we wanted to, in London, or I spent three weeks in the Lake District, you know, before exams were coming up. And it was one of the greatest things I’ve ever done in my life. It was unbelievable. So, I mean, like, on that week that Miss MacDonald had arranged, a friend and I – he was at Oxford. He’d been my college roommate at Georgia – and he and I, the first place we visited was with a viscount and a viscountess in Keswick, and then the next one, we went to a Peel Tower Castle that had been built in 1125 and occupied by the same family since then.

JBG: Wow.

BE: And then, the third one was with a lady Member of Parliament again. We saw a little of her, but she’d say-, well, let me go back to the first one, the Peel Tower people. They were older, and they’d given their house to the National Trust and the whole thing, and they were older and they didn’t want to do a lot of stuff, and they said, ‘But we’ve arranged for you to go to our neighbour who has this castle.’ So, we got to see, you know, other castles. But it was one of the most magical three weeks of my life, without any question. So, I did a lot of that. And then, I had good friends, you know, from college, and I visited them, and that was very wonderful. And then, on the continent, travelling, but so much of where I was going to go was built around going to the opera: so, La Scala, Vienna, you know, that sort of thing. Berlin. And so, that’s how it worked out.

JBG: Wow, that’s incredible

BE: I still have the programmes from those things. I kept those.

JBG: Wow.

BE: So, the people I got to hear, and some of them became really famous after I heard them-, but anyhow, it was just such an enriching experience. And while I was in Oriel, I saw almost everything that the Royal Shakespeare Company did at Stratford. I saw almost all of their productions, you know, and it was just unbelievable.

JBG: Wow, that sounds incredible. And I’m curious, Bob. You shared that that time on the boat together was a really great opportunity to get to know your fellow Rhodes Scholars. I’m curious if the rest of your class continued to play a role during your time in Oxford.

BE: Oh, yes. I had very close friends there. But I was determined I was going to get to know, you know, the British students and the Scottish students too. My college was a very Scottish college, and so, I belonged to the Scottish reels club, and, you know, that was wonderful.

JBG: Great. So, as you’re approaching the end of your time in Oxford, are you still envisioning that perhaps being a lawyer and going to law school would be a next step for you?

BE: Yes, I was. And so, anyhow, I didn’t know what being a lawyer meant, really. And it was funny: where do you go to law school? Especially at that time, you know, Rhodes Scholars could get into most law schools they wanted to go to, and so, I had many choices. And I had sat at table on the ship with a friend of mine who had been at Brevard with me, and his girlfriend was going to go to Oxford, and she was leaving Yale Law School after a year to be with her boyfriend because at the time Rhodes Scholars could not be married. So, anyhow, I remembered her saying, you know, ‘If you talk to a Harvard Law School student, they’ll say, “I wouldn’t be anywhere else, but I’m not that crazy about the place.”,’ and she said, ‘At Yale Law School, we wouldn’t be anyplace else, but we loved it.’ And it as on that basis that I decided to go to Yale. I didn’t know anything about Yale. I thought I’d go to Princeton law school, and of course, they don’t have a law school. I didn’t know that. [30:00] So, anyhow, I was naïve about so many things. I was learning the world.

JBG: Yes. And as you were travelling through your law school experience, did you have an idea of what kind of law you might want to practise?

BE: No, I had no idea whatsoever. If anybody had asked me at the time to say it, I would have said, a litigator. But I don’t know. I mean, I was not quite sure what litigation was, but I would probably have said litigation because of the debating I had done in high school and at college. I was captain of the debate team at Georgia.

JBG: Oh, great. And so, where did your journey bring you after Yale, after you graduated from law school?

BE: I came immediately to Atlanta to go to work. I was 27 by that time, and I was asked whether I’d be interested in a clerkship or something, and I said, ‘I need to go to work.’ I was 27. And you know, time to move on.

JBG: So, you spent over 50 years at what is now Alston & Bird. Was that the firm that you joined upon moving?

BE: I joined the same firm, but it was a different name - Alston, Miller & Gaines – at the time. And I went there because Hugh Hodgson’s son Dan was a partner there, but also, the secretary of the Rhodes selection committee I had gone through, John Moore (Florida & Balliol 1951), he was at that firm. So, anyhow, at least I knew two people there.

JBG: Yes. And what was the focus of your work during those earliest years of your law career?

BE: Well, they had no focus. At that time, you did everything that was expected of you, and I’m so grateful that I had that experience. It was really good for me. And I had a little, you know notoriety. Backtracking a little bit, after my second year, I spent time with Debevoise & Plimpton, a great firm, and knowing about the musical resources in New York and being in this firm and being offered a job, I was very tempted to stay in New York. But I said, with my credentials and everything else, and with my family, ‘That’ll go a lot further in Atlanta than it will in New York.’

And so, I came back at that time, and I’m so glad that you didn’t have to specialise those first three or four years. I had thought that I might be a litigator, but Dan Hudson had come to Yale and he asked me what I’d be in and he said, ‘You’re not mean enough to be a litigator,’ and he was probably right. And so, as it turned out, I was doing everything, trying a little of this, trying that. That’s what the firm wanted at that time. But the first business that I attracted was in estates and trusts, and so, more and more, you know, they thought of me as an estates and trusts lawyer, and when the firm started specialising, that’s where I ended up, and thank goodness, because it’s such a highly personalised practice and just right for me, and I just loved it.

JBG: Would you mind sharing more about that, Bob? What is it about that work specifically that you really love?

BE: Well, you know, I became close friends with my clients, and ended up representing, in three or four situations, four generations of a family. And so, my clients became my close friends, my close friends became my clients, and it just worked, and I had some special clients. You know, it was a good fit for me, and I just loved it. I loved my practice, and I hated to give it up after 58 years, but I was 85 years old at the time I retired. But I still miss the clients, still talk to some of them, not doing their documents or planning them but, you know, we talked a little bit about some ideas they may want to consider. So, it was wonderful.

JBG: Yes.

BE: And, you know, they would get to know my wife, Betty, and they loved and she loved them, and it just worked out fine. The other thing is, my principal outside interest is music, especially the opera. Well, if you want to talk about rich fishing grounds in the States for a trusts lawyer, you’re looking for people who go to the opera, because they typically have more money. And so, you know, my extracurricular activities fit into my professional life so beautifully.

JBG: And so, you love of opera, did that love exist prior to Oxford, or did you discover that during your time in Oxford?

BE: No, no. I’ve been an opera fan since I was in high school.

JBG: Okay.

BE: You know, Brevard Music Center added to that, in so many different ways. And Mr Hugh, we were always talking about opera and taking class on opera or whatever else. And so, it had been with me a long time before I got to Oxford.

JBG: And it sounds like that has continued throughout your life.

BE: It has continued. It has been a big factor in my life. I became the head of the group in Atlanta that sponsored the Metropolitan Opera tour to Atlanta and we had the most successful tour city operation. And because of that, I was asked to join the board of the Metropolitan Opera in 1976, I think it was.

JBG: Wow.

BE: And I’m still a member of the board. It has three levels, and at that time, I was not on the lower level, which is called the association. I joined the advisory board and then, I think in 1977 or 1978, I don’t know, I was asked to join the managing board. And so, I was very much involved in the Met as a managing director for almost 20 years. Then you move down to advisory and now, it’s more nominal than anything else. I’m a member of the association. But the Metropolitan Opera has been very centrally important in my life and, as I said, I headed the group that, you know, sponsored the seven nights in Atlanta, seven different operas. It was unbelievable.

JBG: Wow.

BE: I mean, it’s just incredible, and I got to know lots of the stars, and it’s so funny. I mentioned earlier that I decided one of the temptations about staying in New York to practise law had been, you know, the musical opportunities there. Well, coming to Atlanta, I’ve had so many more. I never would have been a member of the board of the Metropolitan Opera. I mean, let me tell you, that’s a big deal. If I had been in New York, nothing would have happened, but it happened from Atlanta.

JBG: Wow.

BE: It was just unbelievable.

JBG: Wow. And what incredible longstanding service, and to serve an element of your life that is so important in a way that helps to bring that further to your community is just really lovely, and to give others that experience.

BE: Yes. Well, one of my passions has been trying to take people who knew little about the opera or music in general and saying, ‘Well, let me tell you why this is wonderful.’ I taught a music class, not every Sunday, but, you know, annually I had a seven-week stint teaching a music class at All Saints’ church. It had nothing to do with church except that was the location. But, you know, just taking people by the hand, saying, ‘Let me tell you why Debussy is really special,’ and they just love it. And it’s like somebody before going to a hockey game. I know nothing about hockey, but basically, if somebody would take you by the hand and say, ‘This is what’s going on. This is what to look for. There are some special treats you can get,’ and if you do that, you just eat it up, and people in my class, they seemed to eat that up, and I’ve continued doing it.

JBG: Wow.

BE: You know, so, I don’t do it on a regular basis yet, but now, I do it periodically, and I’m doing a music class at All Saints’ in early November [40:00] that will talk about the music of Advent. I’m cheating a little bit. It’s going to be much broader than that. But I love doing that and I have the knack for it. I think that, you know, I’ve got a teacher’s knack.

JBG: You said that was in early November that you’ll be teaching at All Saints’?

BE: Yes.

JBG: That’s so lovely. Wow.

BE: But, you know, also, the Atlanta Opera, which is doing so well, they’re in the middle of doing the Ring operas. And so, last spring, we got The Valkyrie. So, anyway, I’ve been used to doing operalogues, so, I have an operalogue in my house and have, you know, people come, and we take them by the hand and try to say, ‘Listen. This is what is wonderful about it. Listen for this,’ you know? I love that. And this coming spring, I’m going to do two, one on Verdi’s Macbeth and I’m going to do one on the third of the Ring operas, Siegfried. And our house seats comfortably, you know, for a class like this, about 25 people, and that’s all I want to have, and I take these people by the hand, and say-, and I work so hard, and they get a handout. I them little leitmotifs and we talk about the subtleties of it, and it’s fun. I just have a passion for that.

JBG: That’s really lovely.

BE: And I used to do a programme, before the Met came to Atlanta – and this started before I became president of the group supporting the Met – and it was called ‘The Opera Sampler.’ And, you know, I would get local singers and I would coach them and accompany them and all of that, and we would at least have a snippet about each of the seven operas the Met going to perform, at the opera sampler, and it was one of the joys of my life, and an incredible amount of work, and I loved doing it.

JBG: Yes. Oh, that is so lovely. And it leads me beautifully into my next question, because I was hoping to speak with you in more detail about his incredible service work that you did beyond your professional career and during your professional career. And I know that you’ve been very involved with the University of Georgia and continued to have a wonderful relationship with them, and just so many other areas of service and advocacy for the arts, and I was wondering if you would mind speaking to what’s inspired you to really nourish those relationships and really lean into that service to your community and beyond.

BE: Well, you know, I felt like I’ve been given so many spectacular opportunities: the Rhodes, you know, being able to go to Oxford and Yale Law School, all that. But you know, I do have to say this to you: you know, you put those three institutions-, and I’m stealing guess this from somebody who was a Rhodes Scholar from Georgia, and he said, in his case you, ‘I have degrees from Oxford and Yale, but I got my education at Georgia,’ and I feel the same way.

JBG: Yes.

BE: And it was unbelievable. So, you know, giving back to Georgia is so easy for me, because it’s done so much for me. And I got to be chairman of the foundation with all these old men – they were all old white men at the time – and I got on the officer ladder and became chairman when I was 39 or 40 or whatever else, and I’ve been really active ever since. That’s over 40 years, I mean, at that level, and I’d been before. And then, on the music side, that’s just exercising a passion, and I love doing it. We have a foundation that’s controlled by partners of Alston & Bird and I became chairman of that in 1983 and was chairman for about 40 years. And I seem to have no imagination: I get in this job and it lasts for 40 years or 58 years or whatever else, you know, and that’s how you can really make a difference. So, I mean, you’re learning all the way, and I’m constantly wanting to get better. And so, that’s, kind of, how I’ve stayed involved that way. And the music has provided so many special opportunities. Jimmy Carter and I became friends. And so, you know, for example, he made me the chairman of the state arts commission. Now, he wouldn’t give us any money, but I had that special experience, you know, doing that and developing that relationship with him, which has remained special.

JBG: Really lovely.

BE: And I’ll just have to tell you one story. Betty and I would always invite the Carters to go to the opera with us during his term as governor, and they came and, you know, he’s really interested in all of those things. We almost had no other president who was so interested in cultural things and arts things, but that led to our friendship. So, he got to the White House and the first major cultural event they had in the – whatever it’s called. I’m missing the name of the room. I forget-, but it was to have this great pianist, Horowitz, perform at the White House. And so, he invited, you know, Betty and me to come up for that. It was unbelievable.

JBG: Wow.

BE: And then, at the Metropolitan Opera, I helped arrange for a special children’s ballet, The Babar, to come to the White House for their embassy children’s party. And then, the Met always wants a sitting president – not only the Met, but every major cultural-, ‘Oh, if we could just get the president to come.’ So, the Met was trying to get him to come and I thought, ‘Well, maybe I can help.’ So, I had represented him. He’d been a client. And so, I used the private, you know, mail system we had to say, ‘I’m so glad that the Met is encouraging you to come. I hope you will go, because there has never been a sitting president go to the Metropolitan Opera,’ and that too, and I thought it might take. So, then when he’s going, he accepts the invitation, he invites Betty and me to go with him.

JBG: Wow.

BE: And so, we got to fly to Washington and I was just going to take a taxi to the White House and this guy in his raincoat comes out and says, ‘Mr and Mrs Edge’ So, he takes us to the White House and we’re taken to the Lincoln Bedroom. So, we got to spend the night in the Lincoln Bedroom, flew Air Force One – that’s the helicopter – from the South Lawn to Dulles, and then got on Air Force One from Dulles to New York, and it was all unbelievable. And then we came back that night and spent the night at the White House. But it’s very interesting: when Betty and I were sitting with the Carters on the front row of the main box at the Met, and they were performing Aida, that was the same opera with the same cast that we had taken them to in Atlanta. And so, I had all these, you know, things like that. It was just great.

JBG: Wow. What an incredible experience.

BE: Yes. And we’ve maintained our friendship. My wife, Betty, is a photographer, and we had used one of her beautiful photographs on our Christmas card, and we’d stayed in touch with the Carters, but Betty got a call from Rosalynn Carter’s secretary, and she said, ‘Oh, Mrs Carter likes that and would like to see more of your photographs, and could we arrange that?’ And she said, ‘Of course, we’d love to,’ and then this secretary said, ‘They are available for dinner on 17 October.’ This was in March, and she said, ‘They are available for dinner.’ So, they came to our house two years ago, you know, for dinner, and we had entertained them before, but they came, and we were a nervous wreck, because they didn’t walk too well at that time. But it was a wonderful evening. So, anyhow, that’s been one of the rich things to my life, this friendship we’ve had with them, because they’ve been so nice to us.

JBG: That’s really, really lovely. We’ve spoken a little about your longstanding service to other organisations, and you’ve been such a [50:00] longstanding friend of the Rhodes community and served as president of the AARS, and have been an incredibly dedicated member of selection committees for many years, and we’re so grateful for that, and I would love to ask two questions. One, what inspired you do stay involved with the Rhodes community in that deep way? And two, what about your continuing relationships with the Rhodes Scholar community have you found personally most meaningful and most rewarding?

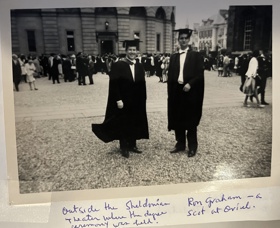

BE: I see. That’s lots of questions. I’ll start with, how did I get involved? I came down in 1962, and there was some kind of gathering of Rhodes Scholars in, like, 1965, and Courtney Smith asked me to speak, so, I spoke. That was the first, kind of, invitation that, sort of, I had gotten. And then, when they had the 1983 reunion in Oxford, they asked four Rhodes Scholars from around the world to speak, and Robin Fletcher – he was the Rhodes Warden at that time, and a nice guy – he asked me to be the American speaker at the reunion in the Sheldonian. So, that was the next thing. As a result of those two speeches, I was asked to join the AARS board, and so, I did, I would go to the meetings. We had a sailing dinner or lunch, you know, at that time, because there was no sailing, but this was before the Scholars were departing for Oxford, and anyhow, I was on that board and I’d served two terms. We had never done anything as far as I was concerned.

And so, the nominating committee chairman called and said, ‘We’d like to nominate you again,’ and I said, ‘Please don’t,’ and he said, ‘Well, what’s wrong?’ And I said, ‘We don’t do anything.’ I remember we had a debate whether or not we could afford to have printed envelopes, and I thought, ‘That’s not what I want to do.’ And so, anyhow, they said, ‘Well, we’re sorry you feel that way, but anyhow, thank you very much.’ Then I got a call back later, saying, ‘Okay, if you were, kind of, more involved, what would you do?’ and I told them some of the things I would do and they said, ‘Thank you very much.’ And so, I thought that was the end of it. Two weeks later, I got a call saying, ‘We want you to be the president,’ which is so ironic. And I was lucky, because of the Loridans Foundation at my firm, that I was a trustee of. We had a policy that if a partner was involved with an organisation, they would provide some support. So, they gave me $10,000 a year for each of the years I would be in office. Well, the AARS didn’t have any money whatsoever, and it didn’t do anything. They did plan, you know, a nice reunion one year, and nice people.

But anyhow, so, that’s when I put together a terrific team: Ila Burdette (Georgia & Christ Church 1981) and John – you know, I’m missing his name. He was wonderful. So, as a team, I suggested-, so, I had sat with these people at the luncheon, these Rhodes Scholars off to Oxford, and I sat with them and said, ‘Well, what do you think about New York?’ and they said, ‘Well, we arrived this morning and we’re leaving this afternoon.’ So, they didn’t know anything. I thought, ‘Well, that’s just terrible, that we’ve got, you know, people going off to England and they’ve never done our major city, or whatever.’ So, that’s how the Bon Voyage came up. And it was funny: the old guard on the board didn’t want to do anything. They didn’t think we should do activities like that. I basically said, ‘Well, you don’t have to come. We’re going to do it,’ and I had the money, from the foundation, to pay for it. So, anyhow, I was on a $10,000 budget.

We started the Bon Voyage weekend, which remains the major activity of the association. And also, Ila Burdette started the newsletter that gives you the biographies of everybody, because before then, we got ‘Robert Edge, Georgia, Oriel,’ and that was about it, and you got a letter, and nobody knew anything about anybody. And Ila started, you know, putting that newsletter together and it’s still fabulous, you know. So, that was my four years. And we went to the White House, to see Bill Clinton (Arkansas & University 1968), and I took them to the Metropolitan Opera, for the Bon Voyage weekend. Unbelievable, because I arranged for the to go to the opening night of the opera. I had those special opportunities. On another occasion: we had the heads of all Oxford colleges, and they were invited to a rehearsal at the Met. So, you know, so many of these things just tied in together so unbelievably and so wonderfully.

JBG: That’s so lovely, and what a remarkable legacy with regards to the Bon Voyage weekend. It’s incredible.

BE: And, you know, Elliot Gerson (Connecticut & Magdalen 1974) and I have become close friends, and he came down to the one of the last-, well, I was the secretary. I served on those committees in Atlanta and Alabama, and went to Florida once, and maybe someplace else. But anyhow, I was on those committees for 31 times.

JBG: Amazing.

BE: And I don’t know if that’s a record, but it’s got to be close.

JBG: Yes.

BE: And I loved doing that. That was so much fun, and I appreciate the opportunity to have been asked by the American Secretaries to play that role.

JBG: And thank you for doing so, Bob. It’s incredible, your service to the Rhodes community and the impact that you’ve had.

BE: I’ve loved it. It feels fortunate to have had the opportunity.

JBG: I was wondering, Bob, if you would mind sharing, at this point in retirement and at the point where you are in your service to various organisations, what would you say motivates and inspires you today?

BE: Well, gratitude. That’s my major feeling, and I’m just so grateful for the opportunities, you know, I have been given, and that’s what inspires me, and my passion for music, and not just music, but the arts in general. My wife and I have both been very much involved in the arts life of Atlanta. She’s a very terrific photographer and we’re both passionate about the arts. And one of the main things-, during my chairmanship of the Loridans Foundation, we didn’t have much money. We had eight million dollars, twelve million dollars, whatever else, and that’s just a small foundation. So, I felt we should come into a focus, and we came into a focus to support arts organisations, especially those in Atlanta without endowments and without reserves, and another part of that is sponsoring new initiatives that can help elevate those small organisations. And so, anyhow, the Loridans Foundation has made a tremendous difference in the life of Atlanta, especially in the arts world, because we focused on the small organisations and help keeping them alive. And, you know, we occasionally get away from small organisations and to move to a large organisation. So, we have sponsored-, in fact, we have regenerated the restoration of the free parks concerts by the Atlanta Symphony at Piedmont Park.

JBG: Wow.

BE: And we had one recently, and there must have been 13,000 people there.

JBG: Wow.

BE: Just incredible. You know, it’s just unbelievable, and that was such a joy.

JBG: That’s remarkable.

BE: Yes.

JBG: You’ve shared a little bit about Betty, Bob, but I was wondering if you would like to share more about your family.

BE: I’m glad to take that up. They’re central to who I am and what I want to do and all of that. Betty grew up in Columbia, came to Atlanta, and we met and got married in 1969, and [1:00:00] we’ve been happily married since then. We’ve just had our 55th anniversary, and it’s terrific.

JBG: Wow.

BE: People think I don’t have any imagination, because I married the same woman, was at the same firm for 58 years. We’re living in the house that we bought in 1975, but anyhow, it’s all wonderful.

JBG: Wow.

BE: I seem to have these things of staying with something a long time. But Betty, she’s so involved in the arts world, and she has been helpful to the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgie. We’re both involved with that, but she’s especially involved and she works with them. She’s been the head of the friends of the library, and she is as active as I am, and on two hours less sleep each day. And she gets up at five-thirty and goes for a three-mile walk-run and then comes home and gets ready to play a tennis game. So, anyhow.

JBG: Wow.

BE: But she’s wonderful, and she’s a great cook. She’s been at my side with all the activities I have had. We entertain a lot, and that was important to my profession. It’s been important to our extracurriculars also, and she’s a great cook and she entertains so beautifully. We have two daughters, both here in Atlanta, fortunately, and one daughter, Elizabeth, is a psychotherapist. She gets to work from home, which is wonderful. She has three children. And then Phoebe, our other daughter, who had been, kind of, a hippie for many years-, then she decided that she needed to settle down and do more for her own daughter, Emma, who is spectacular. And so, anyhow, she became a lawyer.

JBG: Wow.

BE: Well, she’s a good one, and people say, ‘Well, she’s following in your steps,’ and I say, ‘Absolutely not. She doesn’t follow in anybody’s steps, she’s so independent.’ But I’m so proud of them, and the grandchildren.

JBG: So, how many grandchildren do you have?

BE: Four.

JBG: Four.

BE: Yes. Two seniors in high school, and we have two twins, who are 12.

JBG: Lovely. Oh, great. Well, as we come to the end of our conversation, Bob, I’d love to ask you a few questions related to the Scholarship. So, the first being, what impact would you say that the Rhodes Scholarship had on your life?

BE: Unbelievably impactful. You know, it’s unbelievable. I keep describing the Rhodes Scholarship as the gift that keeps on giving. It’s unbelievable, the doors that are open when people know you’re a Rhodes Scholar. And I think there are good and less good Rhodes Scholars, but it’s just magical. You know, when people find out, they make assumptions from the fact that you are a Rhodes Scholar. And what I know is, being a Rhodes Scholar, there’s so much luck involved in that: what kind of questions did you get at the interview? Who is on the committee? I mean, all of those things. And, you know, I think that virtually everybody that makes what used to be the finals of the Rhodes Scholarship, they could have been elected, just as much as well as those of us who did get elected. So, I have that inner knowledge, but it’s just incredible. I mentioned earlier, I think, that, you know, when the admissions committee for Harvard Law School or Yale or whatever, they see ‘Rhodes Scholar,’ there’s just an automatic presumption this is going to be a strong student.’ So, that helps. And obviously, I never applied for any job except the one I took, and stayed for 58 years, but, I mean, that makes a difference. They make assumptions about you, and that’s a real advantage.

JBG: And as I shared earlier, we just marked the 120th anniversary of the Scholarships last year, and so, it’s a natural opportunity to think ahead to the next chapter of the Rhodes Scholarship, and I’m curious what your hopes for the future of the Rhodes Scholarship might be.

BE: Well, I guess I’m too old-fashioned in that regard. I’m mainly concerned about the American Rhodes Scholarships and keeping those strong and central, and, you know, they have these other programmes, but they are of less interest to me, and I find that’s true of almost all my generation. We’re interested in the American Rhodes Scholars and that community and not expanding that too much. Now, that may be lack of vision, it may be probably old fashioned, or old, or whatever else you want to say, but I think it’s true.

JBG: Thank you. Yes. And I’m appreciative of that, and appreciative of all that you have done to build that community through the AARS in your service to the Trust, to build that continued community for Scholars in the US.

BE: Thank you.

JBG: And then finally, I would love to ask if you have any advice or words of wisdom that you would pass on, either to today’s Rhodes Scholars or the Rhodes Scholars of tomorrow.

BE: Don’t listen to people who were at Oxford more than five years ago, is what I would say. I mean, I’m so amazed. I mean, it has changed so much. All the dynamics have changed, you know, and I have seen some of the older Rhodes Scholars offering advice to the newly elected from, you know, the committee meetings that we have, and I think, ‘Lord, that person, his information ins 25 years old, and that’s not good.’ Think about the changes we’ve gone through in the last 25 years. So, I would say, ‘Listen to the people who know currently what Oxford and the Rhodes Scholarships are all about.’ That’s what I’d say.

JBG: Wonderful. Well, Bob, we’re so appreciative of your partnership in the oral history project and your incredible service to the Rhodes community and friendship and support, and I would love to ask, before we close, if there is anything else that you’d like to share.

BE: No. As I said, you know, my central feeling about all of this, and in my life, in fact, is this gratitude for what I’ve been given and, you know, the opportunities I’ve been given. And, you know, people can talk about the controversy that surrounds Cecil Rhodes. My feeling about Cecil Rhodes, I’m just so grateful to him. He may have been a terrible person, but I’m so grateful for what his vision has provided for me and so many others and, you know, that’s my thing. Let me see. I made a note of thing I’d make sure we might touch upon. I we’ve talked about the Carters and the Met Opera and teaching music and the AARS and small town, and Georgia. One thing we didn’t-, one of my things that I’m proud of, and they’re both related to the Rhodes Scholarship-, right after I was elected to go – and I was the first Rhodes Scholar coming from Georgia in, like, 14 years.

JBG: Wow.

BE: And so, anyhow, there was a lot of, you know, excitement about it, and I was invited to speak to the Georgia legislature. What does a 22-year-old say to the Georgia legislature? Well, that’s when we were going through the integration crisis, and the legislature was debating whether to keep the public schools open or close them, rather than integrate them. And so, what was I going to say? And I was later told I was the first person openly to say on the House floor, ‘Gentlemen, we have got to keep the public schools open.’ And that seems so crazy, that that would be such a, you know, kind of, big statement, but they were going to end up closing the public schools rather than integrate. And so, you know, I took that stand. And, you know, so many of the groups that I came to head, they were old white men, and whatever else, and I played a role in changing that, and I think, you know, I take a real pride in that.

And there’s one more.

Let me see whether I can remember what it is that relates to that too. Oh, I know what it was. This is through the [1:10:00] University of Georgia foundation. At that time, the largest scholarship-, there was one one-thousand-dollar scholarship at Georgia to attract students. There were, you know, a few, maybe ten, at the $500-level, but almost no other scholarships. And so, I thought, ‘Well, one thing that we’ve got to do at Georgia is have some kind of programme that will attract people, because it might cost some people more to go to Georgia than to go to Princeton,’ which was crazy, because they’d get all these scholarships and whatnot at Princeton and get nothing from Georgia.

So, I took inspiration from the Rhodes Scholarships and the also the Morehead, in saying, in saying, ‘We need to have some startup programme that will provide more money to at least keep the good in-state students, at least a couple of them.’ You know, ‘Instead of going to Princeton, come to Georgia.’ So, at that time, we proposed – and it’s based on the Rhodes model – and that’s a merit-based scholarship with a little more money. And tuition at that time at Georgia was, I don’t know, probably $100 a quarter, or something. So, we were going to offer a $2,500 scholarship, two of those. And it turned out that the admissions guy at Georgia, who was a friend of mine, he said, ‘Well, Bob, we really don’t want that. We’d rather have ten $500 scholarships than one or two $2,500 ones.’ And so, I said, ‘Well, actually, my partner and I, Alex Gaines and I, have raised the money. You don’t have a choice on this. If you get it, it’s going to be on our terms.’ And that has become the premier programme at the university.

JBG: Wow.

BE: So, when I think about things I’m proud of doing, that’s very near the top, because we had the idea and started the programme and funded it in the early stage. But then, Bernie Ramsey, and he was a fellow who had made some money in the investment world, and he gave a bunch of money, and that’s what enabled the Foundation Fellows programme to become competitive and offer the kind of opportunities that the Morehead and the Jefferson in Virginia do, and now, it’s on a parallel with that.

JBG: Wow.

BE: And it is out of that Foundation Fellows programme, that I had a role in starting, that the Rhodes Scholars from Georgia come from, the Marshalls. This year, the University of Georgia, if you can believe it, had three Marshalls, which is unbelievable.

JBG: Wow.

BE: But it ended up, only two of them took the Marshall, because the third one took the Rhodes. And so, I mean, that just makes me glow with joy.

JBG: That’s really, really lovely. Thank you for sharing that, Bob.

BE: I love it. I mean, you know, you look back and say, ‘What am I proud of?’ That would be one of them.

JBG: Great. Well, thank you so much, Bob. This has been such a joy. I am so grateful for your time and friendship, and if it sounds good to you, I will end the recording there.

BE: That’s fine. It’s up to you. But I’ve enjoyed it, Jamie, and I thank you very much, and you’re a good questioner.

JBG: Oh, thank you. Thank you. Well, it’s been a pleasure.

[file 1 ends]

[file 2 begins]

JBG: Okay. So, Bob, we’re recording again. You were just sharing with me about the way in which you stayed in touch with friends and family back home while you were in Oxford, and I was wondering if you would mind sharing that again.

BE: Well, I’m pleased to share with you, because when I was gone, from the end of September 1960 to returning to America in August 1962, that’s a long time. I wrote a letter home every day to my parents, and my parents, especially my mother, she kept all of that, and there are something like 710 letters or postcards, and I have them all. And, you know, I’m just so glad to have that, because it reminds me in detail of what went on in Oxford, and that’s how I can absolutely enumerate the plays and the operas and all that I got to see. But I mean, it’s a lot of domestic detail, you know, in these letters, but, you know, for me, it’s very important, and I’m so glad I have that. And when Covid started and I wasn’t going to the office and all of that and I had a little more time, I decided, you know, to write my memoirs, the story of my life, and for that period in my life, having those letters was so valuable. And I’ve read the letters once and made little summary notes, and it’s wonderful to be able to recall all the details of my rich life during 1960 to 1962.

JBG: That’s really lovely. It sounds like such a meaningful way to stay in touch with your family while you were away. Did they have occasion to visit you at all while you were in Oxford?

BE: My mother came, the first summer I was there, and she came to Oxford and met my friends there, and we had a wonderful time. Then we went travelling in Europe for three weeks and so, we did the Grand Tour together, and it was fabulous. My dad had bought me a car. My parents were-, you know, they were so generous. I had some prize money I’d won and I always worked, so, I had that money that could supplement, you know, the Rhodes stipend, and then, my parents were so good to me and generous, and so, that’s how I got to go to all those operas and travel around the way I did, because of the supplements I had from my family and my working, and that sort of thing.

JBG: Lovely. Did your mother share your love of opera?

BE: Well, not really. I mean, she would go, and, kind of, the day after she arrived, we went to Glyndebourne. I, you know, took her there. Of course, Bob Darnton (Massachusetts & St John’s 1960) – he’s director of the libraries at Harvard – he had two tickets, and he went. So, I didn’t have a ticket for my mother and a friend who came with her, but they got to sit in the sitting room while we were at the opera. It was wonderful.

JBG: Wow, that’s really lovely. Thank you so much for bringing that up. I think it’s really important to capture.

BE: Thank you.

[file 2 ends]