Born in Calcutta in 1950, Biswajit Banerjee studied at St. Stephen’s College, Delhi University before going to Oxford to take an MPhil and then DPhil in economics. He taught at Oxford during 1977-82, and then joined the International Monetary Fund, where he became a senior staff member, working across Asia and eastern Europe. Banerjee has taught at Haverford College, the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, Wellesley College, the Economics University of Bratislava, and Krea University. He has also been affiliated with the Bank of Slovenia and Ministry of Finance of the Slovak Republic in senior positions. In these capacities he was a member of the Monetary Policy Committee of the European Central Bank and the Economic Policy Committee of the OECD. Since 2018, he has been Professor of Economics at Ashoka University. Since 2019, he is also affiliated with the National Bank of Slovakia as Expert Advisor to the Governor. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 9 August 2024.

Biswajit Banerjee

India & St Catherine's 1972

‘There were no schools to speak of’

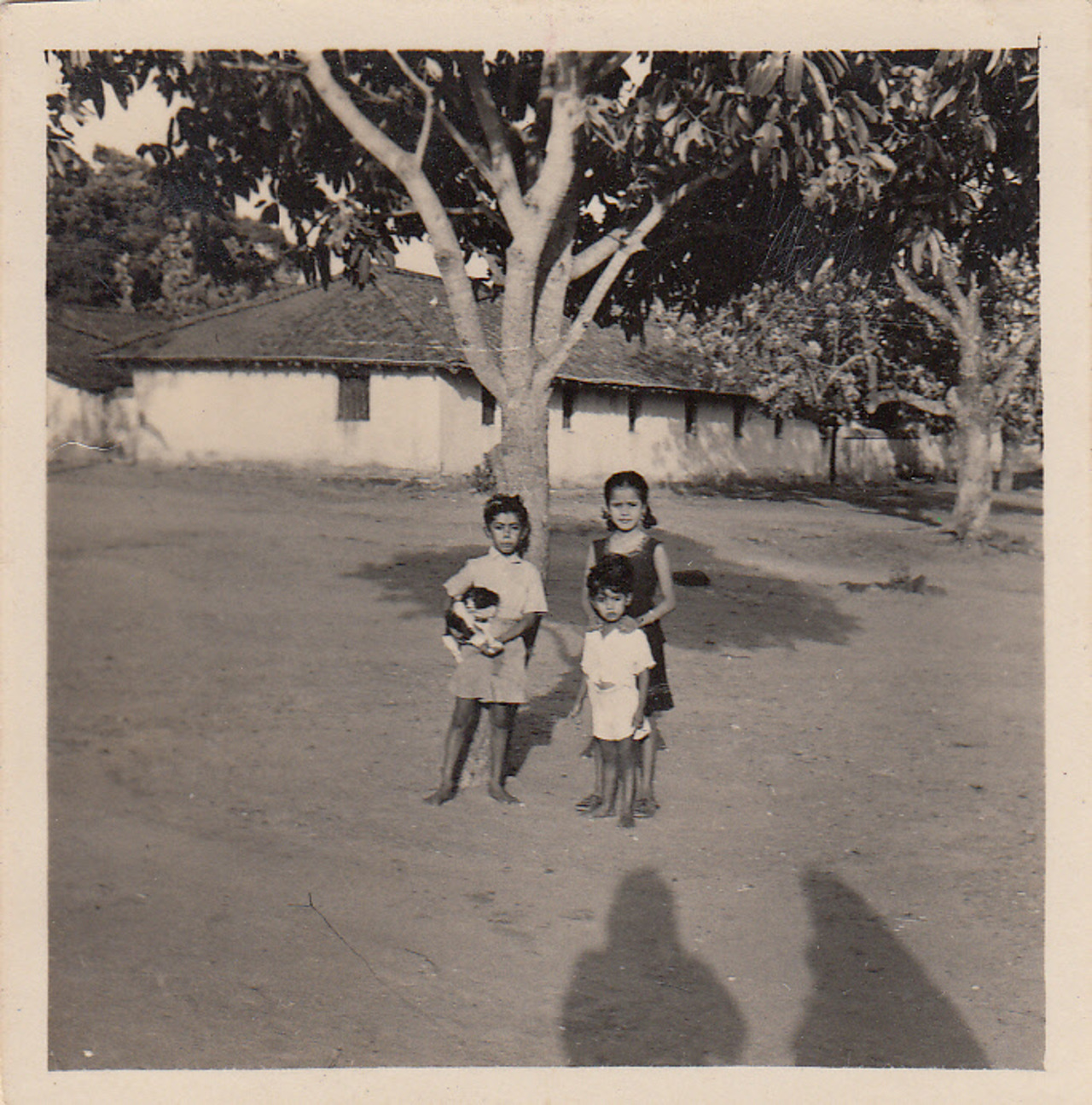

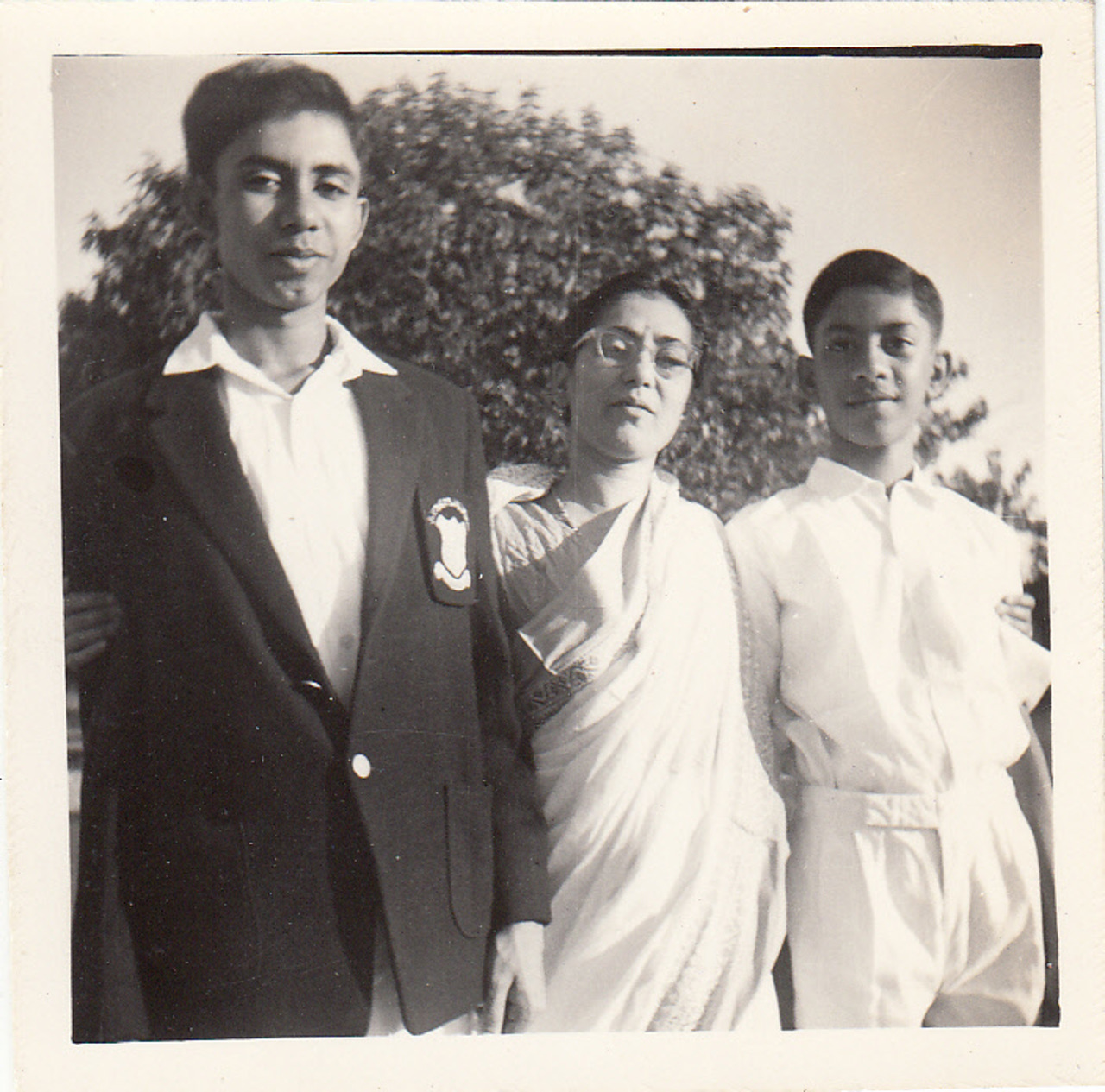

I grew up in a very remote mica mining village about 300 miles north of Calcutta. My father had also grown up there before studying medicine and then returned to the village to practise as a doctor. Our community only had about 100 households and the houses were made of unbaked bricks with a tiled roof. We didn’t have any electricity until I was about six or seven years old, and water had to be obtained from a well. There were no schools to speak of, and I was essentially home-schooled by my mother until I was eight. She taught me and my brother and sister and also the other children from the village who would come. She was not only the only woman graduate in the area, but the only woman there who could read and write.

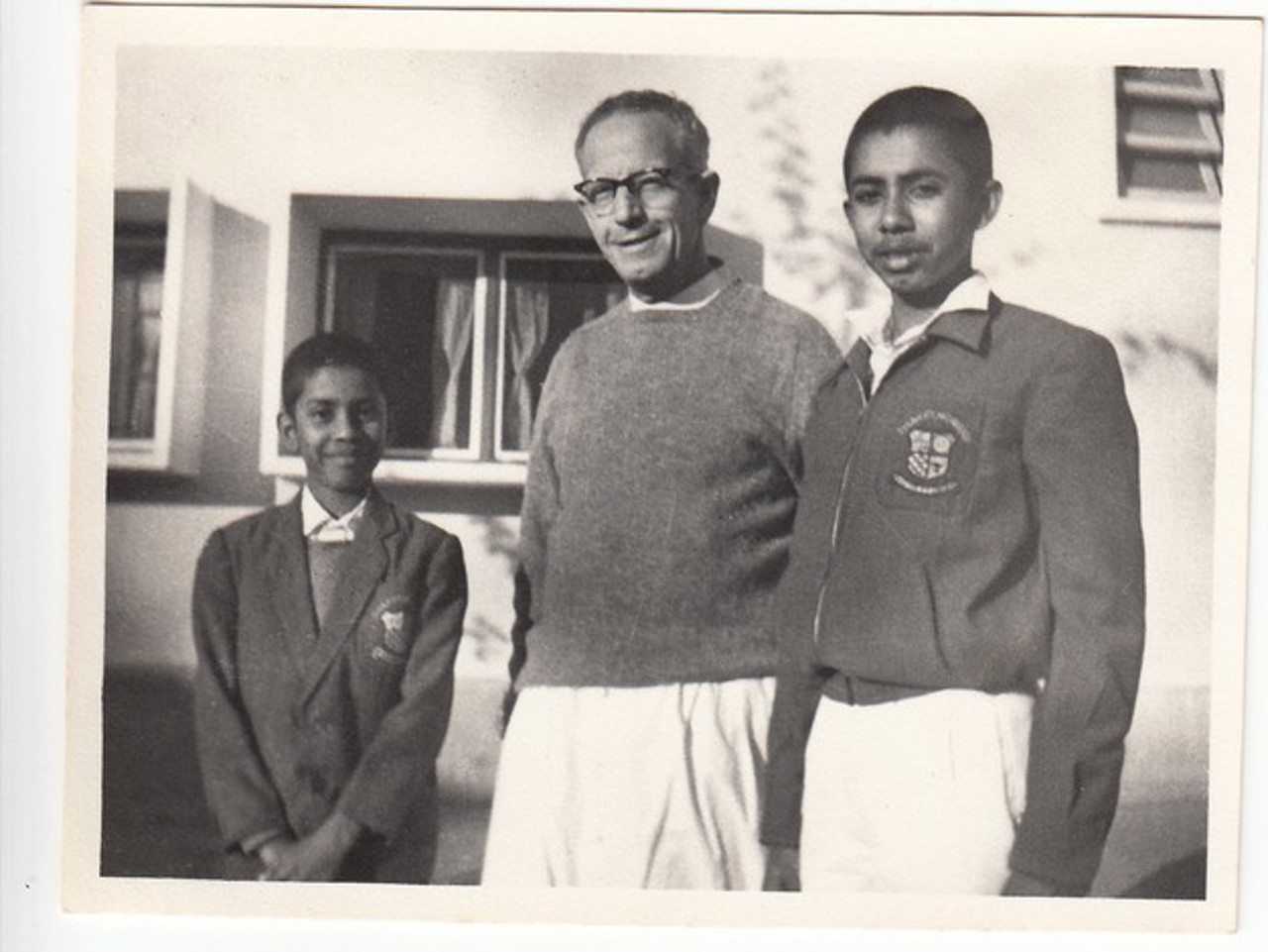

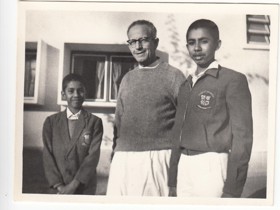

Our village community was very close: we would go into the forest to pick berries together, and we also played soccer and other games together. When my maternal uncle came to visit us from abroad, he brought me a cricket bat and ball, which meant I got introduced to cricket, and so did the village. That was a real hit! I took that enthusiasm with me when I went off at the age of ten to a boarding school in the district town. It was run by Australian Jesuits and we were very nurtured and very well looked after. The standard of education was superior to what those around us were getting. I developed a great interest in other countries in the world, largely because of stamp collecting, and I had lots of pen friends. I still have my stamp collection from that time. To this day, I collect all the first day releases of stamps of selected countries.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

After finishing high school, I went on to St. Stephen’s College in Delhi. It was like going to a foreign country—so far away from home and a totally different environment. When I went to the cricket ground and saw the students playing, I was awed by how sophisticated they were. I wanted to rise to that level and compete, but then I learned that they would all go to a local restaurant after practice sessions for snacks and spend more than my monthly allowance in one sitting. So, I took up soccer and athletics instead. I got selected to represent Delhi in the North Zone Athletic Meet and the National Games. I was running barefoot, and I didn’t even know you had to warm up beforehand. I paid the price for this. I did well for a while, but eventually I pulled a hamstring repeatedly and had to stop participating in competitive athletics.

At St. Stephen’s, several people said, ‘Oh, you’re good in your studies, you’re good in sports: you should apply for the Rhodes.’ I didn’t know much about either the Scholarship or Oxford, but I knew I wanted to go abroad, and it wasn’t something that I could finance myself. So, I said ‘Yes,’ to applying. It was highly competitive, because at that time, there were only two Rhodes Scholars from India.

“Tell me what you see”

My tutor at Oxford was Jim Mirrlees, who subsequently went on to win a Nobel Prize in economics. We would meet once a week and he would ask me to write essays. I was encouraged to read original articles: no textbooks! After two weeks, he told me that I had some basic shortcomings that I needed to overcome. First, I had to stop accepting what I read as the gospel truth. Second, I had to answer the actual question asked. And third, I had to question my teachers more and probe everything I read. I was very upset with this feedback, but he said, ‘I’ll show you.’ He opened an article in an academic journal, pointed at a table and said, ‘Interpret that for me. What’s the narrative embedded in the table?’ I said, ‘It’s written there, in the article,’ but he said, ‘No, forget what you’ve read in the article. Tell me what you see.’ So, for the first time, I started looking critically, and I told him what I saw. Eventually he said, ‘I agree with everything you’ve said, but that’s not what you wrote in your essay.’ Professor Mirrlees showed me that alternative narratives could be crafted out of the same set of information, and I’ve never forgotten that.

At Oxford, I wanted to get assimilated as much as possible. I started playing hockey, and we had matches with other colleges and also with the hockey team in town, which meant I got to know the local population a bit too. I became close friends with some of the other Rhodes Scholars, from the US and Canada in particular. They weren’t economists, but looking at them and what they were planning to do with their lives had an impact on me. It was not so much that the Rhodes opened doors for me as that it opened opportunities: so many things which you would not have done otherwise, or been exposed to, were being shown to you.

‘We had to work fast’

Soon after I arrived at Oxford, I went to a lecture where there were recruiters from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). I said I was interested in a summer job. Even though these summer interships had only gone to US students in the past, they agreed to interview me. After being interviewed again by a senior IMF official, I got the opportunity to work in Washington, DC that summer. It was such a boost. While I was in Washington, I worked in the evenings in the Library of Congress, researching for my MPhil thesis. By that time, my supervisor was Nicholas Stern (Lord Stern today). When he asked me to review a paper submitted by a job candidate at St. Catherine’s, I told him, ‘I can do better.’ He responded, ‘Do it.’ That work, on rural-urban migration in developing countries, became my MPhil thesis topic and eventually my D. Phil topic. I approached the Rockefeller Foundation for financial support to do data collection in India. They agreed, and the Rhodes Trust allowed me to defer the third year of my scholarship. I was extremely lucky.

When I returned to Oxford and finished my D. Phil, I stayed on as a tutor for several years, until it became clear that the landscape of academic appointments in the UK was changing. I had an offer to go to another university outside the UK. But instead, I asked the IMF if I could interview again for a position there. A lot had changed since my summer job, and I really had to think on my feet in response to their questions during the panel interview. But I got the job, and I was very fortunate in terms of my assignments. I worked on the desks for the exotic Pacific island countries of Fiji and Samoa. I also worked on the desk for the Philippines during the period when Marcos was being deposed. In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell and I got involved in providing advice to the newly transitioning eastern European countries. There was unthinkable change taking place, and you didn’t have the luxury of saying, ‘Oh, we need to take our time: let’s get a blackboard and chalk out our plans.’ We had to work fast. Initially I was on the Poland desk, followed by the Czech Republic, Slovenia, and then Macedonia during the Kosovo war. It was far more exposure and experience that I could have ever imagined.

If you ask what my greatest achievement has been as an economist, I would say it was helping to get Slovakia into the Eurozone. Slovakia was going to be rejected, but one of my team members and I went to the European Central Bank and the European Commission and presented information that shifted their position. The result was that just one word was changed in their overall assessment in the report, but that was enough to allow Slovakia to get in. Subsequently, after leaving the IMF I went on to work with Slovakia’s finance minister, and I’m still involved now with the central bank there, alongside my academic work.

‘Be open to whatever you see around you’

For me, the combination of academia and policy work is working really well. I try to bring my experience into my teaching to make it clear that, just as I learned in Oxford, you have to create a narrative from the data and get a gut feeling for what is happening in a country. No textbooks!

To today’s Rhodes Scholars, I would say, take advantage of the opportunities that the Rhodes community and Oxford offer you. Be open to whatever you see around you, assimilate, and try to get to your potential. Because by doing that, you will discover that your potential is far greater than what you think you’re worth at the moment. That’s what I have discovered. The journey I have had from that small, remote village to here: I couldn’t have crafted that story in advance.