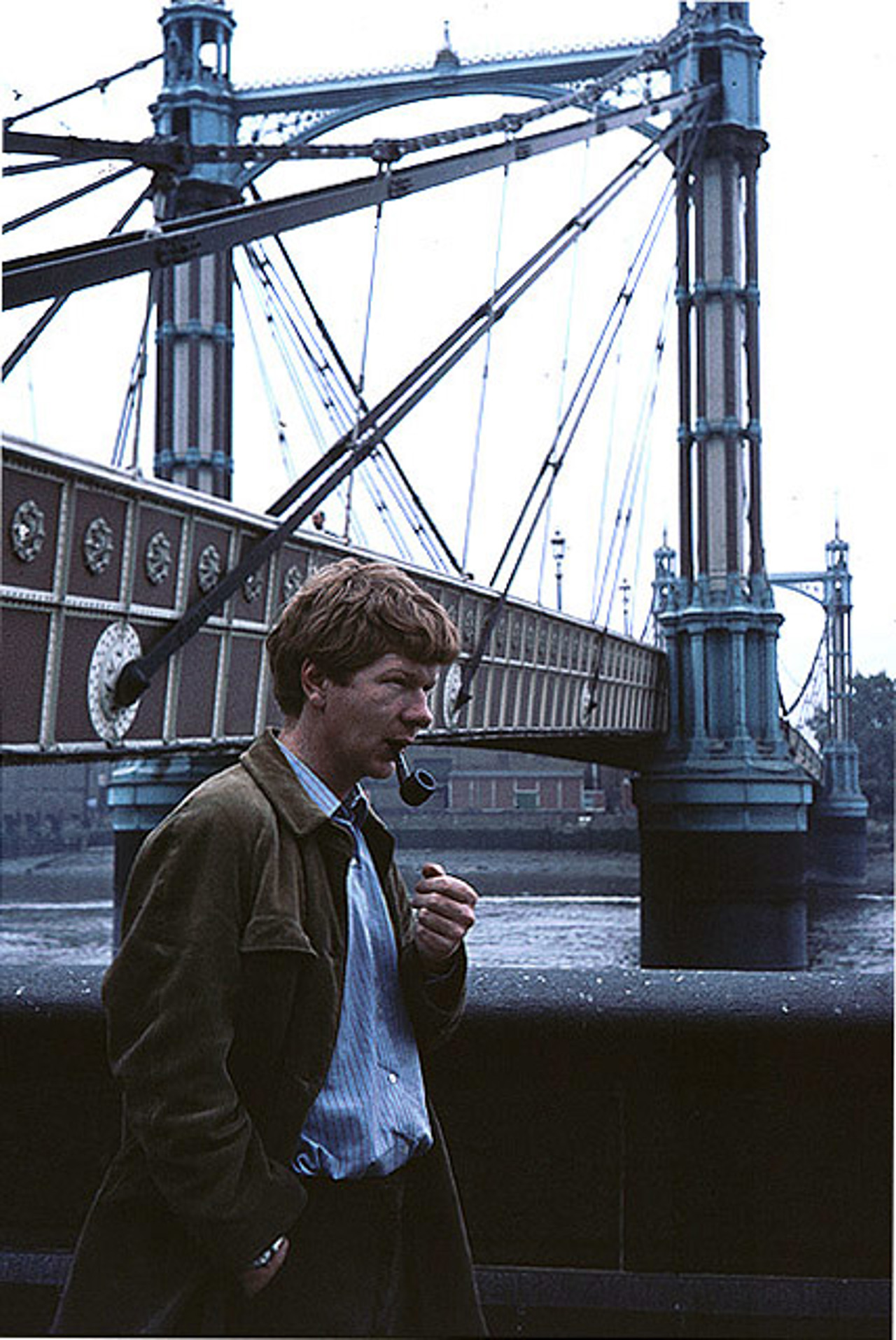

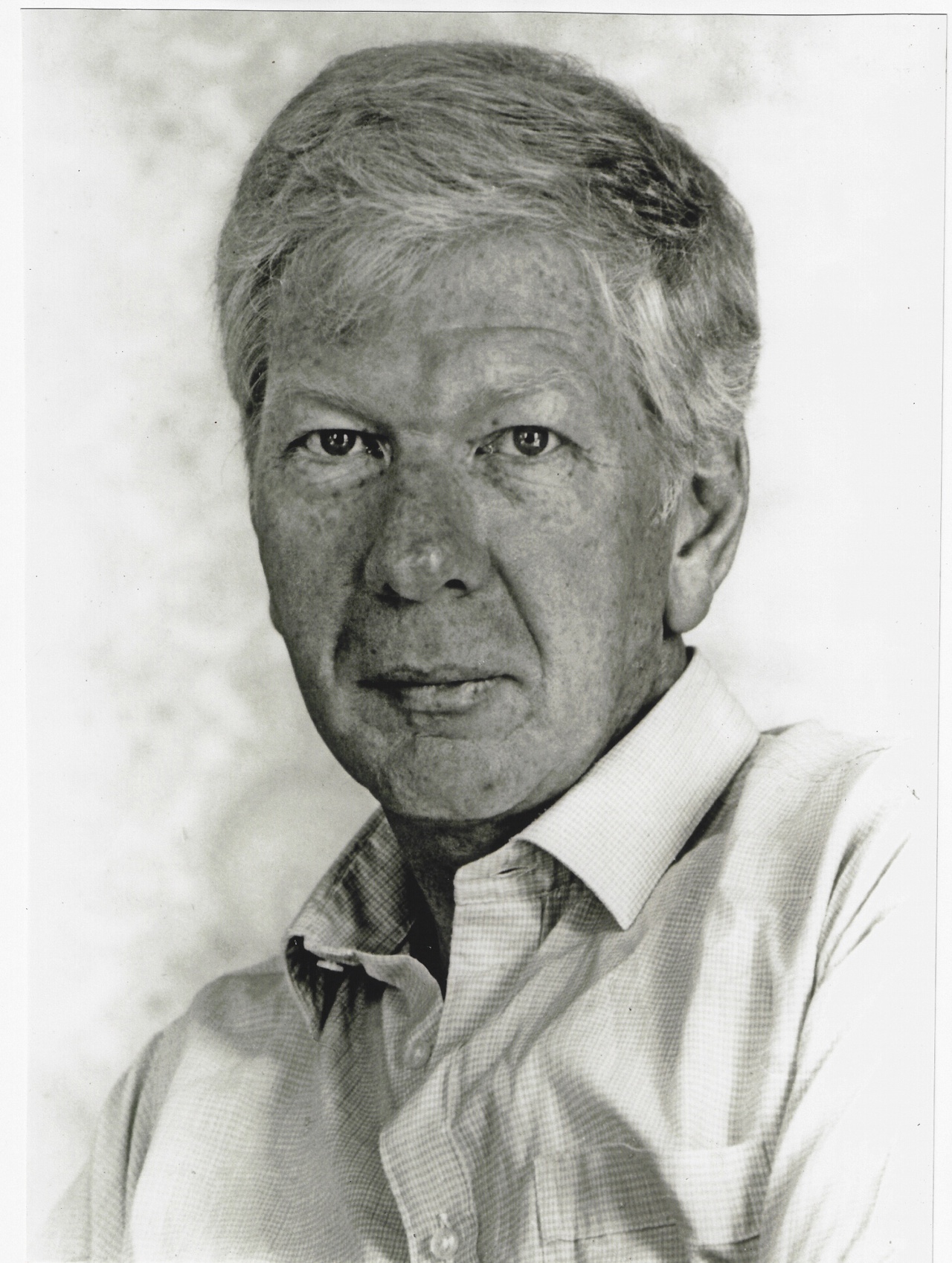

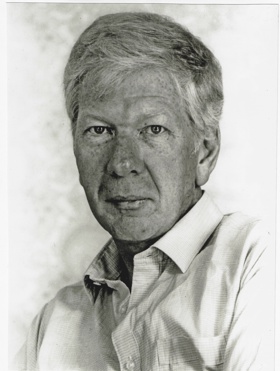

Born on Merseyside in the UK, Bill Johnson’s family moved to South Africa when he was a child. He studied at the University of Natal and was heavily involved in the anti-apartheid movement before coming to Oxford to study for an MPhil in politics. After a period teaching at the University of East Anglia, Johnson returned to Oxford where he became Fellow and Tutor in Politics at Magdalen for 26 years. In 1995, he resigned his fellowship to take up the post of Director of the Helen Suzman Foundation in Johannesburg. Now based in South Africa, he continues to write on politics, and he is also the author of Look Back in Laughter: Oxford’s Postwar Golden Age. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 9 December 2024.

Bill Johnson

Natal & Magdalen 1964

‘A tremendous shock’

My father was at sea in the Merchant Navy, on tankers, and he was very lucky to survive the Second World War. He was torpedoed several times. I grew up in a family of six children, in a working-class area of Merseyside, but in 1957, when I was 13, my father was transferred from the UK to Durban by his employer.

Moving to South Africa was a tremendous shock to me, because it was so different. It was effectively a beach culture and there I was, red-haired and fair-skinned, and my accent was all wrong. Gradually, I settled down, and I even quite enjoyed the school I was at, although it was pretty ropey. There was very little discipline. But I was in a class which had some quite talented boys in it, and that enabled us to teach one another, really.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

I did my first degree at the University of Natal, focusing on history and political science. I was always fairly politically involved from quite a young age. This was the high period of apartheid, and I was extremely dissident as far as that was concerned. In fact, it came up in my Rhodes interview. The chairman of the committee asked why I hadn’t taken South African citizenship and I told him I wasn’t prepared to do military service fighting against my own countrymen. He was terribly upset with me and I thought I’d blown the interview, but it turned out that some other members of the committee were more liberal-minded.

After I’d won the Scholarship, I remember another lecturer at my university was very angry, and she told me, ‘It’s not for people like you.’ There was a tendency in those days for Rhodes Scholars to come from the big private schools in Natal, which was very much not my background. There was also a tendency at that time for the selection committees to emphasise how important it was to be an ambassador for South Africa and to come back to South Africa, which I profoundly disagreed with. Rhodes’ will makes it perfectly clear that Rhodes Scholars should make their contribution all over the world

‘I immediately liked Magdalen’

Settling into Oxford was quite hard, and of course, the weather was terrible! But I immediately liked Magdalen, very much. I started off thinking that I would do a history degree and then changed my mind. Switching wasn’t easy, and when I went to tell the senior history tutor that I wanted to change, he actually stood with his back to me for the whole of the meeting. But the politics tutor, Ken Tite, was very supportive.

I ended up working on my own a great deal, which I liked and was happy with. I made some wonderful friends, both among the other Rhodes Scholars and with the English undergraduates. There were very few events at Rhodes House, but we would go once a term to see the Warden, Bill Williams, who was a man of tremendous principle and character. He had played a very important role as Montgomery’s Chief of Intelligence during the Second World War. He was a natural conservative, but I remember one day seeing him with Bram Fischer (Orange Free State & New College 1931), of whom he was hugely supportive, even though Fischer was a communist. That didn’t matter to Bill, and he talked to me quite a bit about what a wonderful and impressive man Fischer was.

'It’s for your obituary'

Once I started doing graduate work, it was fairly obvious I wanted to be a political scientist. I taught at the University of East Anglia for several years before returning to Magdalen and becoming Fellow and Tutor in Politics there. I wrote on the politics of South Africa and I also became an expert on French politics. I used to go to France a great deal, for every election or referendum, That was a very key part of my intellectual life in Oxford, because David Goldey and I used to give lectures together on French politics. They were always packed out, and years later, people would say to me, ‘I used to go to those lectures. They were fantastic.’ I think it was because they were fun. We would tell stories about things that had happened to us, not just analysing what was going on.

I taught in Magdalen for 26 years. For part of that time, I was also Senior Bursar of the college, and that was very informative. When the new master, Keith Griffin, arrived, Magdalen was in a bad way financially. He and I worked together, sorting out what was a real mess. We even had to sack several people because of corruption. We managed to turn things around completely so that the college was very much back in the black and able to take on a huge restoration project. Cardinal Wolsey had been the bursar in charge when the great tower was built, and I was the bursar in charge when it had to be rebuilt. It was an enormous effort, and one I’m very proud of.

I did go back to South Africa, but not for a decade or so after I left. I had been in trouble with the security police there. As a student, I was part of a group guarding the house of a radical lawyer. The Ku Klux Klan, who were the security police out of hours, came to the house and there was a shootout. It was rough stuff. We were arrested, but I was very lucky, because I still had British citizenship, so I could leave the country without applying for a visa and tipping off the authorities. So, I got out before they tried to detain me. My life would have been very different if I hadn’t been able to leave.

By the time I went to South Africa again, in 1978, things were changing. In 1995, I got gripped by the political change and came back for good. I had wanted the end of apartheid all my life. But running the Helen Suzman Foundation, I found myself having to stick up for liberal values all over again, because the ANC was hostile to any sort of liberalism at that point. Eventually, it had to learn to live with things like press freedom. When the ANC lost its majority in the 2024 election and quite peacefully accepted that, I think that signalled an acceptance of the rules of a liberal democratic system. But South Africa is still massively unequal, and it has huge economic problems. I feel it had a revolution which has stopped halfway, but I hope that will change in the future.

I always wanted to be an academic, but I also ended up doing quite a lot of journalism. I wrote for the Times and Sunday Times about Africa and spent a lot of time in Zimbabwe, doing opinion poll work showing that the opposition should actually have won against Mugabe. His secret police were not happy about that, and when I went there, I had to sneak into the country by a back route, because I couldn’t go through the main airport (I did this many times). In Harare, I switched on the television and saw a whole programme where the Minister of Information was denouncing the evil genius behind all the trouble in Zimbabwe – me. The Sunday Times said, ‘You’ve got to write this up.’ I was scared, but I did it, and all the time I was writing the piece, the paper kept phoning and saying, ‘We need a photo of you.’ I told them I was afraid of being recognised, and they said, ‘Oh, we’re not going to use it.’ I said, ‘Well, then, bloody hell, if you’re not going to use it, why do you need it?’ and they said, ‘It’s for your obituary, don’t you see?’ I could only laugh, but it was a hair-raising period, and high-adrenaline stuff.

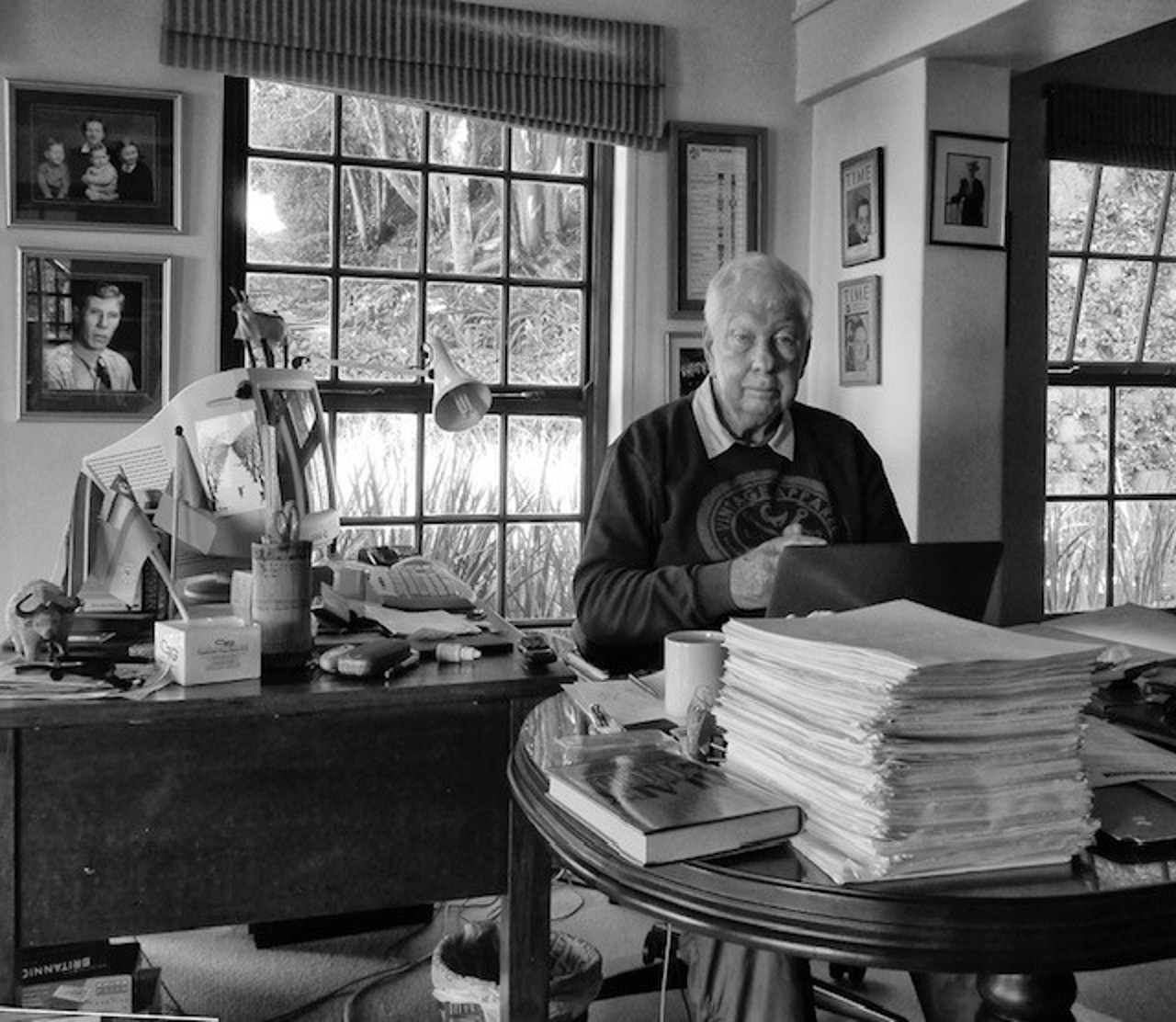

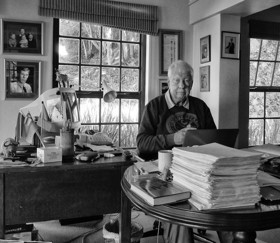

‘I’ll carry on doing what I’m doing until I drop’

I’m retired now, but I’m still writing. That’s part of me. It’s what I do. It’s what I am. I’ll carry on doing what I’m doing until I drop. My research and my writing brings other things too. During the last election in South Africa, for example, I was the lead person for TV coverage of opinion surveys and all the rest. It was very interesting, and it’s nice still to be doing it, long after an age where you might not expect that to be part of your life. I’ve had a much more adventurous life than I’d reckoned on or expected.