Born in 1967 in Lytton, British Columbia, Alison Van Rooy studied at Canada’s Trent University before coming to Oxford to complete a DPhil in international relations. She started her career in Ottawa at The North-South Institute focusing on international development policy, and then moved into the Canadian civil service and held roles with a particular focus on international development assistance. Following her retirement from government, she took on a role with Vancouver Island University, leading the development of a new strategic plan to strengthen access to post-secondary education in an economically challenged part of BC. In 2024, Van Rooy joined the first cohort of Oxford Next Horizons, a six-month experience for those in mid to late career, offering the chance to think, explore and reinvent. This narrative is excerpted from an interview with the Rhodes Trust on 29 May 2024.

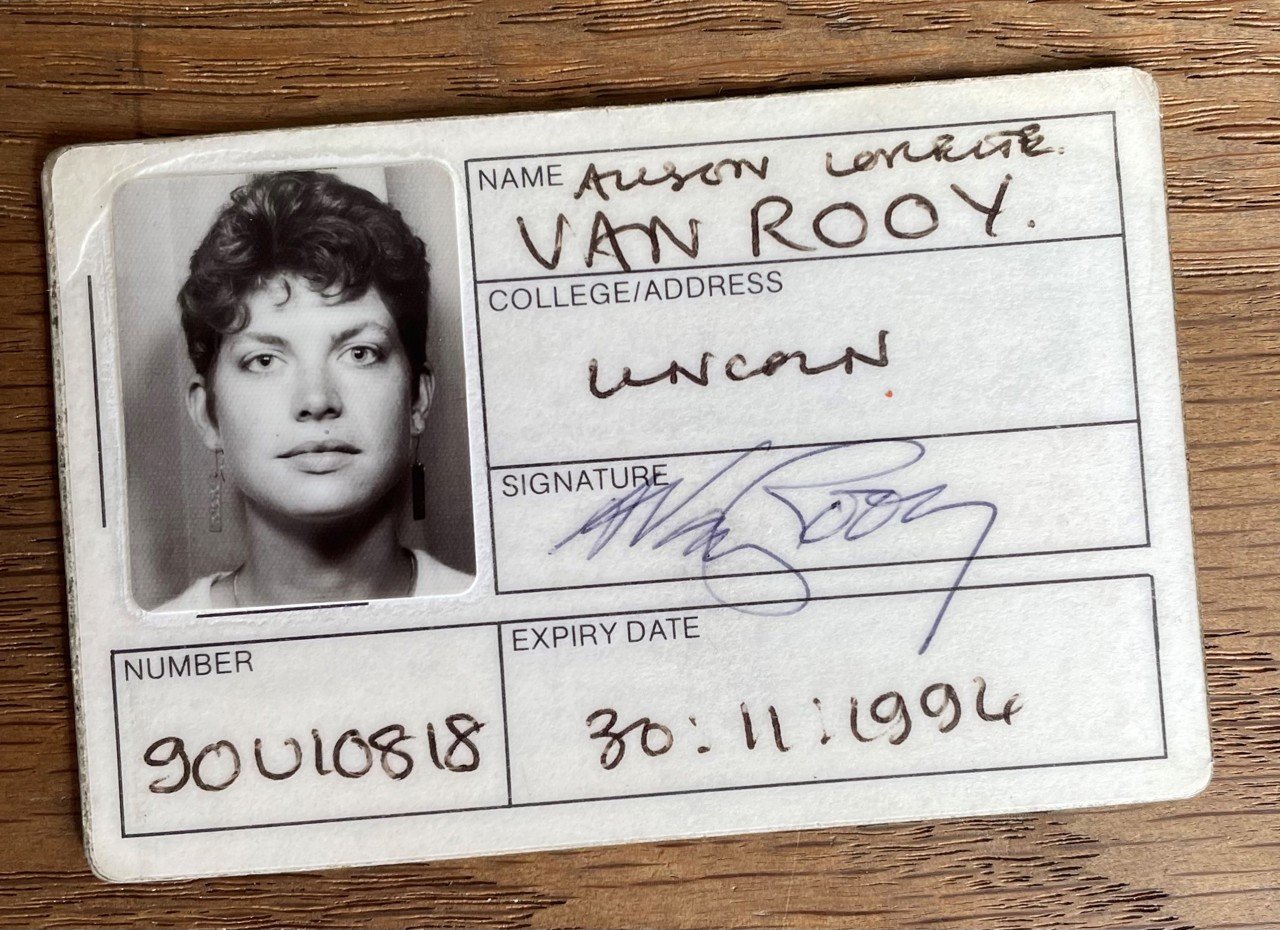

Alison Van Rooy

Manitoba & Lincoln 1990

‘A tremendously important time in my life’

Like a lot of North Americans, I’m the product of immigration from many parts of Europe. I have a Dutch last name but I could as easily had a Norwegian one or a German one or an English one. My mother was American, my father was from Newfoundland, and my brother and I grew up in the middle of Canada.

Partly because my family had come from different parts of the world, I was always interested in looking at the globe. When I was 11, I started to reach out to find pen pals, and at one point, I had 130 pen pals from around the world. It might have been a funny hobby for a kid, but I loved it. I went to school first in the north end of Winnipeg, and I grew up with people from all over the world, including kids from First Nations communities as well. That became such an important part of my life and my experience that when I was 16, I went on to the United World College of the Pacific, part of a network of schools set up on the premise that people can’t live in peace unless they know one another, and they can’t know one another unless they live together. There were kids from 80 different countries at my school.

On applying for the Rhodes Scholarship

Later, I was also part of Canada World Youth, a program that matched young people from Canada and other parts of the world, all working together in both countries. In my case, I spent four months in Sri Lanka, a tremendously important time in my life, being with a family and getting to know a community from the inside.

I became committed to studying international development and international politics, and at the time, Trent University was the only place in Canada where you could do that. It had very innovative programmes and it was wonderful to be in a small place with a group of people who were really committed to making the world a better place. But I wouldn’t have applied for the Rhodes Scholarship if my mum and dad hadn’t been so supportive. They said, ‘Here, you should.’

‘I found a real sense of home with my fellow students’

My years at Oxford were a phenomenal time in my life. It was hard to find a home for my topic, which was the activism of non-governmental organisations internationally. At the time, it simply wasn’t of interest in Oxford in the faculty I belonged to. But I was still able to make important connections and explore ideas, and I found a real sense of home with my fellow students.

There were several things about Oxford that I found surprising. For example, when I applied for the Rhodes Scholarship, I didn’t know Oxford had colleges. I chose Lincoln for practical reasons (even numbers of men and women graduate students and a great reputation for food!), and I made lots of friends there, but I’m not sure it was the best fit for me academically.

Oxford was certainly a great place to try new things, and I rowed and played rugby and joined a choir. At Rhodes House, a group of us stated a newsletter for all of the Rhodes Scholars in residence. It was called the Zimbabwe Bird and it included articles and reflections from Rhodes Scholars about their travels, their studies, their poetry, their political insights.

I didn’t understand British class dynamics, and I certainly didn’t know at first what to do with all that cutlery at formal dinners! But one of the advantages of being a North American was that British people couldn’t really place me in the class system. I had been a student of anthropology, so I found it quite interesting to approach Oxford from that point of view: coming to a new culture and trying to learn the rules.

‘How do you do good things in the world?’

When I went back to Canada, I spent the first part of my career in a think tank. The North-South Institute was at the time Canada’s only think tank focused on international development politics and policy. I worked to develop their programme on civil society, looking at how non-governmental organisations of various kinds form themselves as activists and policy influencers. After spending a lot of time trying to get my own government to change its policies and practices, I decided that I would make more of a difference if I worked in government itself and tried to influence those changes from the inside so I moved into the civil service.

I worked in several different departments, but mostly on international development policy, the thing I care most about. A real peak for me was being involved in Canada’s current and most recent international development policy, called Canada’s Feminist International Assistance Policy.. There’s very good research to show that having a gender-sensitive and women-first policy has impact throughout society, in terms of health, certainly – infant and maternal health and morbidity – but also in terms of economic growth, environmental sustainability, and more. The policy was a powerful statement from the government of Canada about how we were going to spend our international assistance dollars.

I was also involved in a very interesting initiative to set up a Policy Hub at Global Affairs Canada, getting different groups of people together to identify and work on problems. At the time, I was a senior adviser to the Assistant Deputy Minister for Asia Pacific and we were focusing on a series of issues, including the Rohingya crisis and a trade dispute with India. The basic question was, with a circumscribed set of policy levers, how do you do good things in the world with the resources you have?

That was an approach I took with me when I retired and went to Vancouver Island University to help with strategic planning. VIU is a place that works extremely hard at including people; for example, helping people finish their high-school diplomas so that they then can apply to post-secondary education. The university was asking itself, “How can we organise ourselves to make more good things happen?’ It was a lovely way to finish that part of my career.

Now, I’m part of the Oxford Next Horizons Programme. I was excited when I saw that it was being set up. I thought, “Okay, they’ve made this for me.” I had had a very meaningful career but I also had this feeling that there was so much more I could do. It’s been very exciting, very energy giving, to be back in Oxford and thinking about what I want to do going forward. And now, just as when I was in Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, it’s the other members of the programme who are a crucial part of the experience: they’re a remarkable group of people.

“Service to others is the rent we pay to occupy our space on the planet”

I’m very much aware how lucky I am, both in terms of how privileged I was to have been born in a part of the world and in a culture that’s so supportive of women and education, but also in terms of the marvellous opportunities I’ve had that could have just as easily gone to other people. So, my question to myself at this point in my life is how I can continue to give back? I think all of us have a responsibility to make the world a better place.

To younger Rhodes Scholars, I would say, work hard, but not too hard: nobody will ever ask what grade you got. So, follow your curiosity and put your work into topics and subjects that are life-giving, and spend all the rest of your time with good people. For older Rhodes Scholars like me, I would say don’t spend too much time thinking about what you did in the past. Until our last day, we always have a tomorrow, and with that we can do more, and do more wonderful things, more giving things. There’s a saying that goes something like, “Service to others is the rent we pay to occupy our space on the planet,” and there’s always room to do at least a little bit more.