Welcome to the "Rhodes Scholars & China" interview series, where our Chinese Scholars interview Scholar alumni with work or life ties to China, including leaders in academia, journalism, business, medicine, law, and many more fields.

In this first instalment, Xiaorui Zhou (China & Pembroke 2020) interviews Michael Szonyi (Ontario & Merton 1990). Michael Szonyi is Director of the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies and Frank Wen-hsiung Wu Memorial Professor of Chinese History at Harvard University. He is a social historian of late imperial and modern China who studies local society in southeast China using a combination of traditional textual sources and ethnographic-style fieldwork. A frequent commentator on Chinese affairs, Szonyi is a Fellow of the Public Intellectual Program of the National Committee on US-China Relations. Read Szonyi's full biography.

Read the Chinese version of this interview, translated by Xiaorui Zhou, is available: Chinese Translation. For more Chinese-language content, follow Rhodes China on WeChat (ID: RhodesChina) and Weibo.

Xiaorui Zhou (XZ): You enrolled in the University of Oxford’s Faculty of Oriental Studies as a DPhil student in 1990, on the Rhodes Scholarship. Why did you apply for the Rhodes Scholarship and how was the selection process like back then?

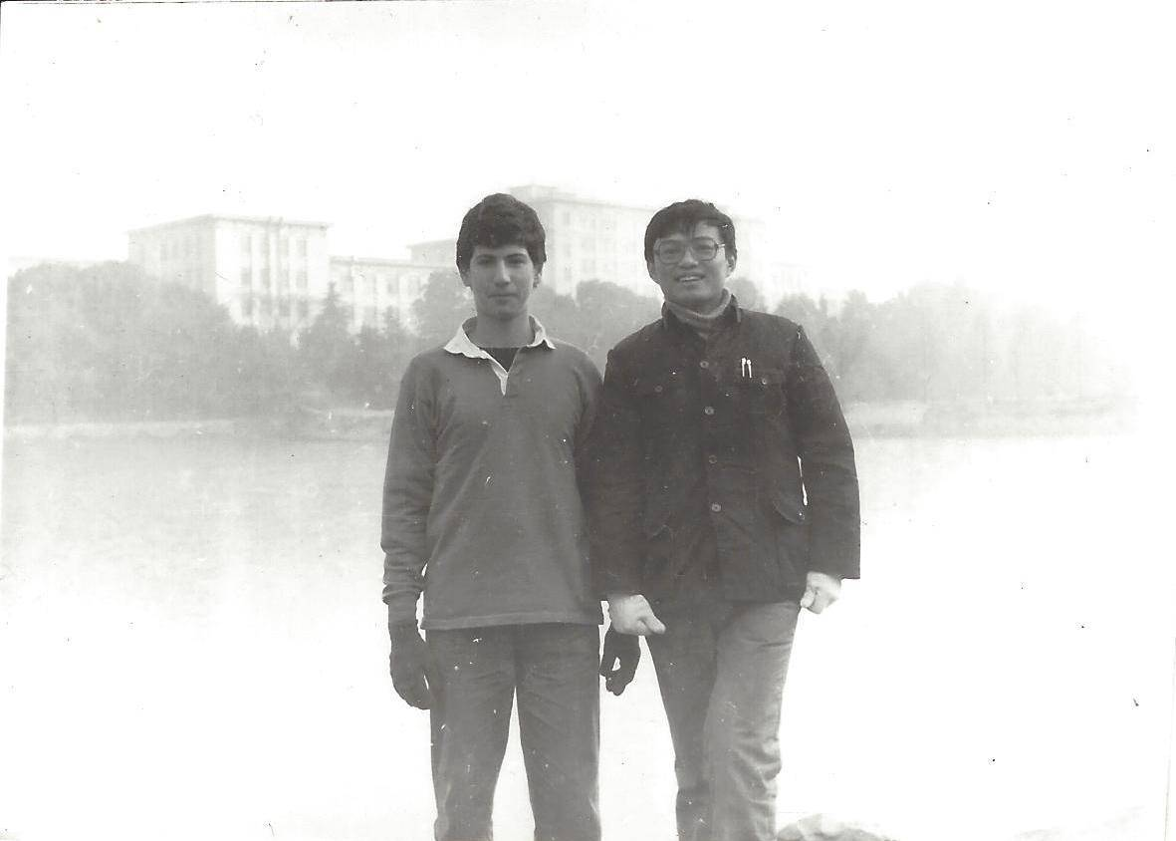

Michael Szonyi (MS): In 1990, I was living in Taiwan, and studying at National Taiwan University. I had already decided that I wanted to pursue a post-graduate degree (and perhaps also an academic career), and the question was where. It was a fascinating time to be in Taiwan, which was undergoing huge political and social changes, so I thought about completing my degree there. I also considered applying to an American university. While I was deciding what to do next, an old friend from my undergraduate days suggested that my profile fit the Rhodes criteria well. He even mailed me the application to encourage me – hard to imagine that there was no internet then. I applied, made it to the interview stage, flew back to Canada and to my surprise was selected.

My sense is that in Canada at that time the scholarships were in the midst of a transition. They had always been considered a mark of accomplishment – a kind of reward for young people who embodied certain values. But I felt that at the time of my election, the committee was equally interested in how the Scholarship, and study at Oxford, could be an opportunity for further development. It certainly was in my case. At the cocktail party the night before the interviews, I was in awe of the other candidates. On paper they certainly looked more impressive than me. But I think I made a convincing explanation for why the opportunity to study at Oxford was the right step in my future development, and was able to link that explanation to my previous experiences, and that was probably the reason I was chosen.