How To Take Career Risks When The Safe Options Look So Good

From a talk with a group of Rhodes Scholars — who are fortunate to have some of the most attractive “safe options” in the history of humanity.

“Know where you’re going. Have a plan. Follow your dreams.” It’s that time of year again…

Nonsense. These are just-so stories successful people tell you after the fact. They distort how it was, back when they were you, at the beginning. And besides, getting early career advice from a successful person is like looking at a star — by the time its light reaches you, it’s old. (Says the pot?)

How does your world differ from what came before?

Power once belonged to institutions, many of them; today it belongs to fewer institutions (each more powerful) and to individuals and their steroided power to create.

With this, the nature of success is changing. Successes were once anointed, by elders. They prized inputs — hard work. Institutions thrived on metering out your sense of progress — skipping three levels in the hierarchy violated their norms.

Anointed success — where you are chosen by those with power — has given way to forged success — where you make your own way.

Anointed successes are hired and work their way up the ranks (from clergy to politics). Forged successes (from founders to artists) live by the products of their work. Almost every career includes at least a bit of both.

Why are the forged successes rising? It’s become easier for others to see our work —ideas or code or companies or creative works — as the distribution of information has become less costly. The gatekeepers are bowing as you pass them by. And as smaller organisations become capable of more, the makers jump from the shoulders of giants. With our professional identities now so public, we the people now own the communication of our own results. Faster flow of information means you can be known sooner. Side hustles lap vocations.

Forged success prizes results — and prices them in many currencies, respect, wealth, freedom, or otherwise. Results refuse to obey norms.

Institutions turn out to be a bad technology, sloppily latching forged accomplishments to individuals’ anointing opinions — and we’re looking for better ones. It’s important to keep working on making our institutions better, because their power continues to shape us. (Ironies: Anointed leadership roles in the very biggest institutions — think Walmart or the US government — have become more powerful than ever. And school is a strange institution — a hybrid of anointed and forged success. Test scores are results; recommendations are anointed. This might be why people who succeed at school are often so-so at life, and why careers of academics straddle the forging and the anointing.)

Maybe you’ve been hired for a job and feel those in power can’t see you, miss out on understanding what you can do. That frustration you feel isn’t because those in power are bad people, it’s because the fun house mirrors of institutions make it harder to see what’s valuable. (When you’re a hammer, everything looks like a nail, and I’m a startup investor, so I’m biased to those who forge. Not to be confused with forgers.)

For many people, being anointed is more enjoyable, more rewarding (financially and otherwise)— and it’s almost always easier. Millions of people do feel seen at work, valued for what they can do. And that’s great.

Forged success is more valuable, when it works. It’s riskier, though.

So how do you forge the shape of your own career?

Ignore the myth that you have an inner voice, a true destiny pointing that way, if only you knock aside the bric-a-brac. If that’s true, we can’t know. And if it isn’t true, then believing it hurts. Instead, pick useful faiths: like the idea that charting your career path is a skill. If it’s a skill, you can practice it and get better. If it’s inherent, then you either “just know” or sit with the suffering.

Charting your career path is a skill.

Test and iterate. Think your direction might be… wanting more money? Try to make more, and see how it feels.

Gather lots of data — unless you “just know,” put yourself in different places. Pick up puzzle pieces until you can see enough to paint in the gaps.

Avoid continuing to trek along with what you’re good at for the sake of continuing to be good. You will probably be great at this, too, but you might not be. If you knew you were, what’s the fun?

Do I wish I’d known when I was your age that I wanted to do what I do now? Of course. But then I wouldn’t be who I am today.

How do you make choices without a goal?

Some recommend to “expand your options,” though we now know too much choice is worse than just the right amount. At some point the joy is in taking the better path, not in bushwhacking yet another.

Have one variable you are trying to solve for: often it’s being around people who are the best in the world at what they do. Then know the limits you want to set — maybe how many hours you’ll be there, or where you want to live, or that you want your parents to be able to brag to their friends about you. The economist in me would call this an objective function, with one variable to optimise and as many side constraints as you like.

(Knowing where you want to live is a particularly important one that talented people often undervalue — pick a place you think will make you happy. Most people lack the luxury of being able to choose where to live. Appreciate your blessings.)

Have one variable you solve for, and as many “side constraints” as you want.

And if you must, then guess. If it feels like you’re getting warmer, bingo.

Acknowledge that the environment in which you place yourself — your co-workers, your closest friends — will shape you. Select the environment by which you want to be shaped.

At some places, if you pick right, it will feel like you’ve sat on a geyser.

Are there risks to avoid?

Well, fatal bets kill. Good poker players avoid being all in. Protect your downside — whether it’s with another income source, or a fallback option. If you’re lucky enough to have those, use them. If you aren’t, create them.

Avoid bets where your happiness will be tied to a dice roll. Only take bets where, even if you lose, you’ll think the bet was worth it.

And, yes, I’m a startup investor — so am I just saying you should start a company? No. Maybe start a side project sometime, see how you like it. “Make no small plans” is more nonsense used to stir the blood, a common tactic in business. Many of the best things ever built started with small plans.

…………………………………….

At earlier points in my life, my One Variable I solved for was the rate of learning. Later, for autonomy.

Today, I want to understand work, so I can empower people. My side constraints are to take time to focus on my health, contribute to a content family, preserve my autonomy to make decisions and live my life the way I want (including controlling travel and work hours), maintain my standard of living, stay in the Bay Area, and attempt to become financially independent enough to back new things without asking others for money. (I do try to remember Denny.)

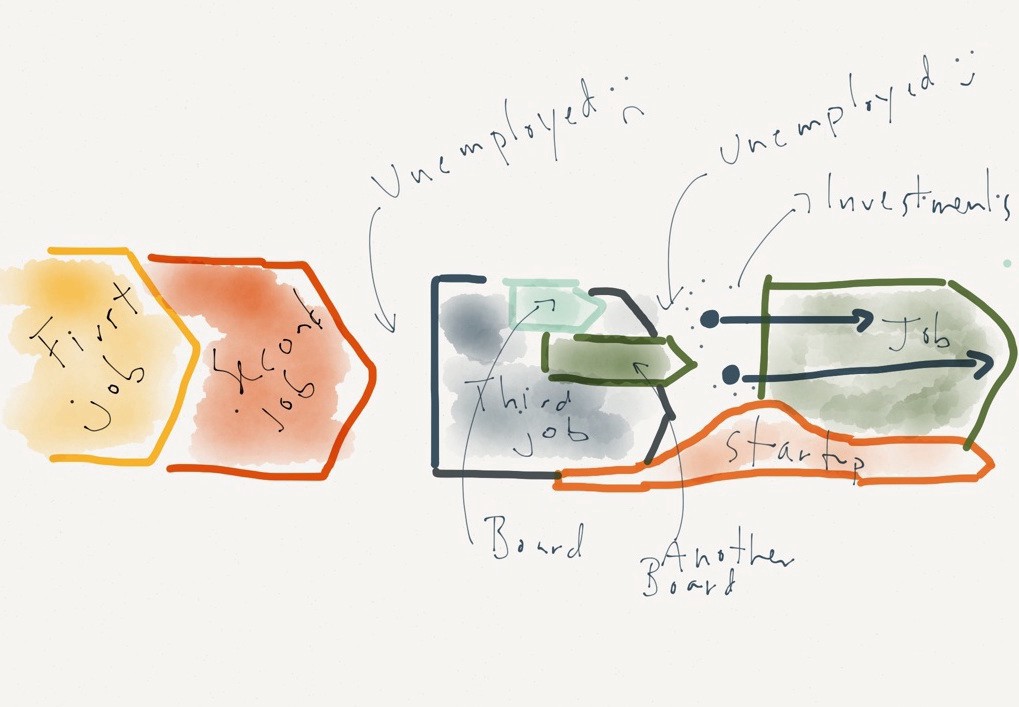

In my messy career I’ve learned that figuring out what you want, professionally, is a skill you can learn.

Even if it’s easier these days to move around from one anointment in an institution to another (and that can be OK), we still live in a world where forged success is more valuable than anointed, institutional approval.

P.S. I’m unsure if I even believe in advice. All advice is autobiographical: Either the giver justifying their own choices or, worse, living vicariously through you, asking you to be their “what if I’d.” This piece is probably the latter, so take it with a boulder of salt.

Thank you to Fritzi Reuter, Shu Nyatta, Dhruva Bhat.

Roy Bahat (New York & Lincoln 1998) is head of Bloomberg Beta, an early-stage venture firm that invests in startups making work better. He also teaches media at UC Berkeley and serves on the board of the Center for Investigative Reporting. Roy has spent time making startups, as a corporate executive, in government, media, and academia -- and was named one of Fast Company’s Most Creative People in Business.

This blog originally appeared on Medium, 18 June 2018.